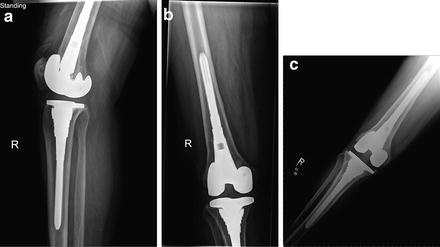

Fig. 8.1.

AP (a) and lateral (b) X-rays on initial presentation demonstrating a stable right total knee arthroplasty with no evidence of loosening or mal-alignment.

His past medical history is significant for protein-S deficiency for which he was on coumadin with an IVC filter in place, hypertension, depression, and coronary artery disease with history of a myocardial infarction. He had a contralateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) performed approximately 4 years prior without complication. The initial implant used was a cemented posterior stabilized construct, with a rotating platform tibia and a resurfaced patella.

8.2 Management

Given the acute onset of symptoms and positive arthrocentesis, a diagnosis of acute late periprosthetic infection was made and the patient was taken the following day to the operating room for irrigation and debridement with polyethylene exchange. All infected-appearing tissue as well as the pseudomembrane was removed. Betadine scrub brushes were utilized to scrub the femoral, tibial, and patellar components, which were noted to be well fixed with no signs of loosening. All previous ethibond sutures were removed and the wound was irrigated with 6 L of normal saline pulse lavage. A new polyethylene insert of the same size was implanted. A hemovac drain was placed prior to fascial closure with #1 prolene sutures. This was followed by 2-0 subcutaneous PDS suture. The skin was closed with staples.

Due to the patient’s hypercoagulable state, he was placed on lovenox postoperatively and bridged back to coumadin. A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) was placed for 6 weeks of Cefepime in addition to oral Rifampin as recommended by an infectious disease consult obtained while in the hospital. His rehabilitation included range of motion exercises, full weight-bearing and gentle muscle strengthening similar to a primary total knee replacement.

Postoperatively, the patient did experience some pain relief but denied resolution of his pain. Approximately 2 months postoperatively (2 weeks after cessation of the IV antibiotic therapy), the patient returned with persistent right knee pain, erythema, and an effusion. Range of motion of the right knee was 0–105° with no evidence of instability. Repeat laboratory markers revealed an ESR of 25 mm/h, CRP of 21 mg/L, and a peripheral white blood cell count of 6. Aspiration was also performed at that time revealing 23,000 WBCs (differential of 92 % neutrophils) and cultures eventually growing MSSA.

The patient was taken back to the operating room after normalization of his INR for the first step of a two-stage exchange procedure for explant of the right knee arthroplasty and placement of a molded antibiotic-loaded knee spacer (Fig. 8.2) utilizing 3 g of tobramycin per cement package. The knee was closed in a similar fashion with hemovac drain in place. At the recommendation of infectious disease, the patient was given an additional 6 weeks of antibiotics consisting of daptomycin.

Fig. 8.2.

Postoperative lateral (a) and AP (b) X-rays demonstrating insertion of antibiotic-loaded articulating spacer.

After explant, the patient was again bridged back to his coumadin with lovenox and began a physical therapy protocol in the attempt to maintain range of motion and to encourage weight-bearing. After completing his antibiotic course, his labs were again drawn demonstrating normalization of both ESR and CRP prior to reimplantation. The patient was replanted approximately 7 months later with a posterior stabilized revision construct consisting of hybrid diaphyseal engaging stems and porous metaphyseal sleeves on both the tibia and femur. Antibiotic cement was used in a limited fashion proximally under the tibial component and distally under the femoral component. Physical therapy following revision utilized the same protocol used following primary total knee replacement. Postoperatively, the patient recovered well and had no further complications with the knee.

8.3 Outcome

Most recent follow-up 5 years after reimplantation reveals the patient has healed his incision nicely with no complaints of pain, drainage, or instability of the knee. X-rays reveal well-fixed implants in good alignment (Fig. 8.3) with range of motion of approximately 5–110° actively and passively. He has been participating in physical therapy off and on and has returned to his preoperative level of activity without restriction.

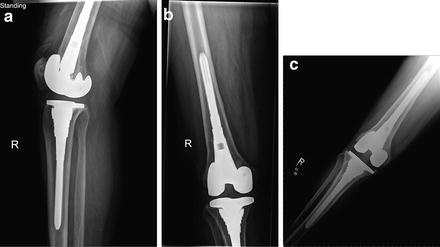

Fig. 8.3.

Most recent lateral (a) and AP (b, c) X-rays after two-stage exchange arthroplasty.

8.4 Literature Review

8.4.1 Risk Factors

The typical presentation of a patient with late acute prosthetic knee infection is sudden onset of painful range of motion, swelling, and warmth in a previously well-functioning total knee implanted greater than 1 year [1]. There is growing evidence that the presence of diabetes with end-organ damage, heart disease, and pulmonary complications are important risk factors for the development of acute hematogenous infection [2]. Although no single comorbidity has shown to provide statistical significance for increased risk of infection, a total number of comorbidities greater than three as described by the Charlson comorbidity index has consistently been shown to be a significant risk factor in hematogenous infection [3].

In addition, Swan et al. [4] found that 88 % of late acute hematogenous prosthetic knee infections described some type of sentinel event prior to their diagnosis and presentation, with the most common being an open wound or skin infection. This finding has been supported also by Maderazo et al. [5] where similar organisms recovered from a distant skin source were also recovered in the infected joint.

A great amount of attention has also been given to the possible hematogenous spread of bacteria from the oral cavity after dental procedures. However, many authors discredit this belief due to the low incidence of streptococcal or oral pathogens ultimately grown from periprosthetic infections. In a 2010 case-control study by Berbari et al. [6], not only were dental procedures not a risk factor for subsequent periprosthetic infection but also patients who did take antibiotic prophylaxis did not decrease their rate of infection following a dental procedure. Although the connection between transient bacteremia and oral procedures appears to be well documented, there is no evidence that this bacteremia results in prosthetic joint infections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree