Performing Arts Medicine

Sonya Rissmiller

Katie Weatherhogg

“The body says what words cannot.”

Martha Graham, Dancer and Choreographer, 1894-1991

INTRODUCTION

Performing arts medicine is a branch of physical medicine and rehabilitation devoted to the care of musicians and dancers. A key concept of performing arts medicine is the ability to prevent, recognize, treat, and rehabilitate musculoskeletal injuries as related to each student, amateur and professional performing artist. This chapter discusses in further detail common injuries found in musicians and dancers, including injury management, rehabilitation, and barriers to care. The injuries primarily focus on the upper limbs for musicians and the lower limbs for dancers. Practitioners of performing arts medicine should have a solid understanding of musculoskeletal medicine and an appreciation for the physical effort and specific movement required to perform in each of the various arts.

DANCE MEDICINE

Most current medical literature focuses on ballet (1, 2, 3, 4). Research must therefore be extrapolated to treat other types of dance. The majority of this chapter focuses on the injuries associated with ballet, understanding that the performing arts practitioner treats all types of dance including modern, jazz, tap, folk, ethnic, ballroom, and hip hop, all of which can lead to medical problems (5,6). Each style places demands on the body and may vary with respect to footwear, dance surfaces, training, and alignment.

Dance Training

Ballet training typically begins for female dancers by 5 or 6 years of age. Young dancers often begin training daily for 2 to 6 hours at a time with annual or semiannual performances by age 11 or 12. In order to pursue ballet professionally, preteen and teenage students with high-level ability and skills attend intensive summer programs, and those with the greatest ability and potential move to preprofessional ballet schools for year-round training. These exceptional students may participate in work-study programs with school in the morning, blended with class and rehearsals in the afternoon and evening. Some dancers obtain their general education degree early to join professional companies, while others continue to dance through college and join companies later. A large component of a dancer’s early career involves auditions. These tryouts can be critical to obtaining roles in performances and in the development of a professional career. Performing arts physicians need to acknowledge the high importance of auditions and should inquire about upcoming dates. This knowledge may aid in the decision to tolerate a higher risk of reinjury than under normal circumstances, as long as documentation of discussion and decision is thorough.

Terminology and Positions

Knowledge about the technical requirements for dance is important. Performing arts medicine practitioners excel at understanding the biomechanical demands placed on dancers and the maladaptations many dancers use to compensate for inadequate anatomy, conditioning, or biomechanics. Dancers should be evaluated for onset of symptoms and triggers, in addition to demonstrating the movements or positions that reproduce the symptoms (7) (Fig. 55-1). Common dance terms are

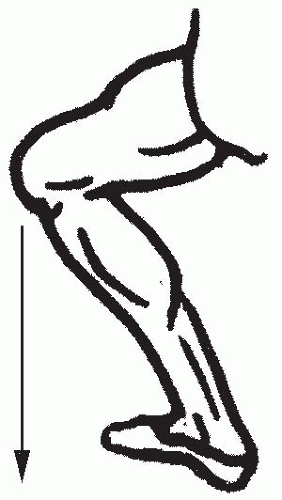

Plié—heel remains on the floor with the knee in flexion (Fig. 55-2)

Grand plié—heels lift off the floor with deep knee flexion

Pointe—dancing on the tips of the toes, ankle in maximal plantar flexion (Fig. 55-3)

Demipointe—weight bearing on the metatarsal joints, ankle plantar flexion, and metatarsal joint extension (Fig. 55-4)

Barre work—dance classes are divided into three stages: barre, center, and movement from the corners across the floor. Barre work involves holding on to a bar during warm-up exercises and conditioning.

Center floor work—The second stage of a dance class performed in the middle of the studio involves balancing, jumps, and short sequences of movement.

Causes of Injury and Risk Factors

Extrinsic

There are many common extrinsic and intrinsic causes of injury and risk factors in dance. One extrinsic factor is the type of dance floor. The presence of adequate shock absorption and the degree of surface friction can lead to injuries of the knee, foot, and ankle if there is too much surface resistance. Likewise, a floor that is too firm leads to fatigue and injuries such as tendonitis of the leg and foot (8).

Footwear can also influence injuries. Most ballet dancers wear either slippers, composed of only fabric or leather and no structural support, or pointe shoes, which are made of a solid toe box, metal or wood shank, and fabric. Theoretically, pointe shoes act as an additional stabilizer of the foot as demonstrated by cadaveric studies (9). However, these shoes are not designed to provide adequate stability or shock absorption and have changed very little since the 1600s (4,8). Furthermore, principal dancers may wear out one to three pairs of pointe shoes per performance because if the shoe becomes too soft it can often lead to injury, such as tendonitis and stress fractures (9).

Intrinsic

Intrinsic causes of injury or risk factors include, but are not limited to: malalignment of the lower limbs, muscle imbalance, and inappropriate training (7,8,10,11). Proper alignment in ballet is based on turnout (the maximal amount of external rotation at the hips), which will ideally enable a dancer to stand with the feet placed at 180 degrees in first position. Although dancers may appear to be able to achieve 160 to 190 degrees of turnout at the feet, they may not have the corresponding degree of external rotation at the hip (12,13). When the lower extremity is properly aligned in first position (14,15), the knee flexes directly over the foot. Many students will not be able to attain this ideal position and will compensate by forcing their turnout. “Rolling in” forces the feet into a position with a valgus heel and forefoot pronation (Fig. 55-5), leading to subsequent collapse of the medial arch and thereby increasing the torque on the ankle and knee (Fig. 55-6) (7,9,11). Young dancers, both female and male, will sometimes increase their lumbar lordosis in order to tip the pelvis anteriorly and thus obtain increased hip rotation. In addition to potentially leading to low back pain, other complaints may arise from the increased torque placed on the lower limb (7,11).

Muscle imbalance is often due to inadequate strength or altered flexibility. Ballet emphasizes hip flexion, external rotation, and abduction, which can lead to weakening of the antagonist muscles (8). Deficits in strength and endurance at the hip may lead to injuries of the foot, ankle, and knee (21, 22, 23). Focusing the treatment on the injured joint without addressing any underlying hip muscle imbalances may frustrate both dancers and physicians alike as pain and dysfunction are likely to recur. By nature, dancing en pointe involves loading the ankle joint in maximal plantar flexion with accompanying distal pressure placed on the first and second toes. Significant ankle flexibility and intrinsic foot strength are required to maintain the position (9). Elite and professional dancers usually display appropriate alignment as such alignment problems typically extinguish careers prior to this level. Generally speaking, at the professional level, limb injuries more often result from overuse rather than from issues of alignment. In young dancers, immature skeletal formation may contribute to musculoskeletal injury. Similarly, growth spurts may further lead to muscle imbalances, where a gain of 1 to 3 in. in growth might overwhelm the muscular strength required to move and change positions. As a result, young dancers can develop muscle tightness relative to bone length and/or inadequate strength, particularly in the hip rotators (16).

The effects of inappropriate training are often related to factors such as excessive duration and intensity (7,10). As in other aesthetic sports that place a large degree of importance on the appearance of the performer such as diving and figure skating, dancers often have delayed menarche due to caloric restriction coupled with large amounts of exercise (17). As dancers are often subjectively judged on their appearance, eating disorders are common in preprofessional dance schools with some reports estimating up to 30% of the students being effected (18, 19, 20). Such behavior can often place dancers at increased risk of developing the “female athlete triad”: disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis (7,10).

Incidence of Dance Injuries

In 2005, a UK national survey reported that 80% of 1,056 professional dancers sustained at least one injury per year (24). In a similar study of dancers at a sports medicine center, 90% of injuries occurred in the lower extremity and two-thirds were classified as overuse injuries (25). Of all the disciplines in dance, classical ballet necessitates the longest training, places the most physical demands on the musculoskeletal system, and studies indicate that 67% of all dance injuries occur from the practice of classical ballet (4).

Common Dance Injuries

Spine Injuries

Dancers routinely suffer spine injuries similar to many other athletes, including but not limited to fractures of the pars interarticularis and sacroiliac dysfunction. Delay in the treatment of pars fractures may progress to fibrous unions that will not calcify and potentially result in spondylolisthesis. If underlying biomechanical issues are corrected within an appropriate time frame, dancers may continue dancing with spondylolisthesis. However, dancers should restrict activity with relative rest in the event of a new pars fracture and may require either an antilordotic modified Boston brace or a nonspecific conventional lumbar corset (26).

Sacroiliac pain occurs frequently and is often difficult to resolve (7,27). Jumping and leg extension on the affected side may incite pain in dancers experiencing sacroiliac dysfunction. Special physical examination maneuvers such as Gaenslen’s test and the Gillet’s test are useful in diagnosis. Treatment of sacroiliac dysfunction may include mobilization of the joint and pelvic stabilization exercises.

FIGURE 55-6. “Rolling in” at the knee, with tracking medial to the foot. This often occurs with insufficient hip external rotation strength and forcing of the physiologic barrier. |

Repetitive microtrauma from extreme extension or hyperextension may result in damage to posterior elements, such as the pars interarticularis, facets, pedicles, and spinous processes (28). Poor technique and control may cause painful injuries to the periosteum during hyperextension. Although this injury is painful, it requires no special treatment other than correction of technique unless it proceeds to pars fracture.

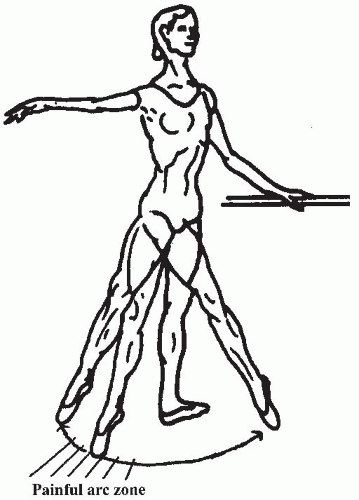

Hip Injuries

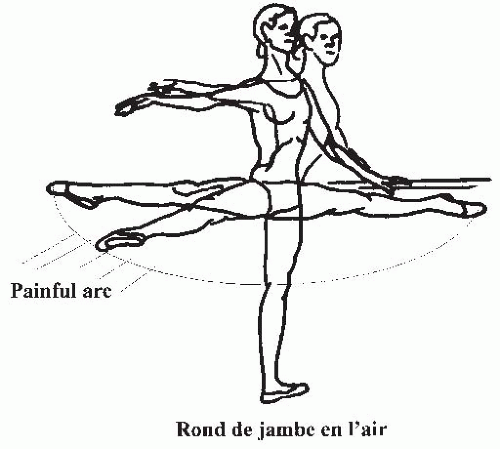

“Snapping hip” accounts for 50% of hip problems in dancers, occurring either medially or laterally with or without pain (4). When it occurs laterally, the iliotibial band or tensor fascia lata snaps anteriorly and posteriorly over the greater trochanter when landing from a jump in poor turnout and with excessive anterior pelvic tilt (7) or as the thigh moves between the anterior and posterior positions. “Snapping hip” may also occur medially and is sometimes referred to as “iliopsoas syndrome” (29) (Fig. 55-7). This phenomenon occurs when a hypertrophied iliopsoas crosses the femoral neck when bringing the hip into extension during a semicircular motion known as rond de jambe (7) (Fig. 55-8). A dancer with this injury will experience intense anterior groin pain during this arcing movement, particularly as the iliopsoas stretches over the femoral head from medial to lateral; it is also typically more painful while in the air than with the foot on the floor (30). “Snapping hip” rarely causes significant disability and responds well to

focused stretching, hip strengthening (especially the external rotators, adductors, and internal rotators), and antilordotic postural control (11,30). Other hip injuries such as labral tears, osteoarthritis, stress fractures of the femoral neck, hip avulsion injuries, and femoral neuropraxia have been described in the medical literature as well (7).

focused stretching, hip strengthening (especially the external rotators, adductors, and internal rotators), and antilordotic postural control (11,30). Other hip injuries such as labral tears, osteoarthritis, stress fractures of the femoral neck, hip avulsion injuries, and femoral neuropraxia have been described in the medical literature as well (7).

Knee Injuries

Knee problems are often attributed to insufficient hip strength in external rotation or forcing greater foot turnout than physiologically possible (as noted previously). Hip weakness or alignment problems are the usual causes of knee pain. The typical sports-related knee injuries also occur in dancers, including anterior and medial collateral ligament sprains, patellar subluxation, and patellofemoral syndrome (31,32). Tears and injuries often result from slips, twisting falls, and improper landings from jumps. Diagnosis and rehabilitation of such injuries follow standard sports medicine guidelines.

Acute Ankle Injuries

Ankle sprains are the most common acute dance-related injury (7). These sprains commonly occur when a dancer loses balance while landing from a jump while the foot is in plantar flexion. They can also occur from rolling over the lateral aspect of the foot while on demipointe (9). Interestingly, in full pointe, the ankle is relatively stable as the posterior lip of the tibia locks on the calcaneous and thus the subtalar joint locks in varus. It should be noted, however, that slight dorsiflexion relaxes the chain and may predispose the ankle to injury (10). As noted with other sports, the anterior talofibular ligament is the weakest ankle ligament and most susceptible to injury (9,10). The Ottawa ankle rules recommend ankle radiographs if a patient is unable to walk three steps or if there is tenderness over either malleoli (10). Specific rehabilitation of acute ankle injuries includes pool therapy, plantar flexion exercises, proprioceptive retraining, and peroneal strengthening with an emphasis on resuming full mobility of the talar, subtalar, and transverse tarsal joints (7,9).

Overuse Ankle Injuries

Anterior Ankle Impingement

In anterior ankle impingement, the anterior distal tibia and the talus pinch the bony or soft tissue during ankle dorsiflexion, particularly during grand plie (7) (Fig. 55-9). The medical history is often notable for chronic anterior or anterolateral ankle pain on jump landings or a limited demi-plié (9). Other mechanisms and the source of pathology of ankle impingements are found in Table 55-1.

Physical examination might include an effusion, audible click, palpable tenderness, and limited dorsiflexion when compared to the contralateral side. Pain is also present with passive dorsiflexion when the knee is bent (9). This is primarily

a clinical diagnosis. Treatment includes restricting pointe and center floor work, encouraging exercises at the barre, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), local injections, modalities, and in refractory cases, arthroscopic surgery (7). Return to a full plié position may take 3 to 4 months (9).

a clinical diagnosis. Treatment includes restricting pointe and center floor work, encouraging exercises at the barre, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), local injections, modalities, and in refractory cases, arthroscopic surgery (7). Return to a full plié position may take 3 to 4 months (9).

Posterior Ankle Impingement

Posterior ankle impingement is caused by the posterior tibia and calcaneous compressing the posterior talus and surrounding structures. This impingement may frequently be caused by a symptomatic os trigonum (7,9). The os trigonum is an accessory ossicle posterior to the talus which is often asymptomatic (11) (Fig. 55-10). When a dancer positions herself in extreme plantar flexion, the os trigonum is pinched between the tibia and calcaneous. Patients will present with posterior ankle pain, worsened with plantar flexion (11), and the pain and inflammation may limit the dancer’s ability to perform pointe, as well as the movement from flat foot to demipointe. Os trigonum syndrome will also cause pain with both active and passive plantar flexion (7). This pain is usually posterolateral, behind the peroneal tendons and often with associated ankle stiffness (9). Diagnosis is again primarily clinical; however, a standard lateral view ankle x-ray can demonstrate the presence of an os trigonum (7). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also show bony edema of the distal tibia and inflammatory changes surrounding soft tissue (7). Treatment of posterior impingement syndrome includes dance training modifications including limiting pointe-work, NSAIDs, physical therapy modalities, and exercises, with the refractory case leading to surgical excision (7). Changing pointe shoe wear to a half or three-quarter shank to more easily facilitate pointe-work may also provide some relief (9).

TABLE 55.1 Anterior Ankle Impingement Etiology | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Achilles Tendinosis

Achilles tendinosis is classically seen in pointe overuse, excessive pronation and “forced turnout” during plié, or the wearing of too tight pointe shoe ribbons (10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree