3 PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT AND PATIENT SAFETY IN TRAUMA CARE

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT IN TRAUMA CARE

A universal condition of trauma center designation is that specified injury data must be collected, analyzed, and maintained. In addition, the data must be monitored routinely by the trauma program in an effort to improve performance. The standards published by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma in Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient are the foundation for performance review in trauma centers.1 These standards have continued to evolve and were most recently updated in 2006.

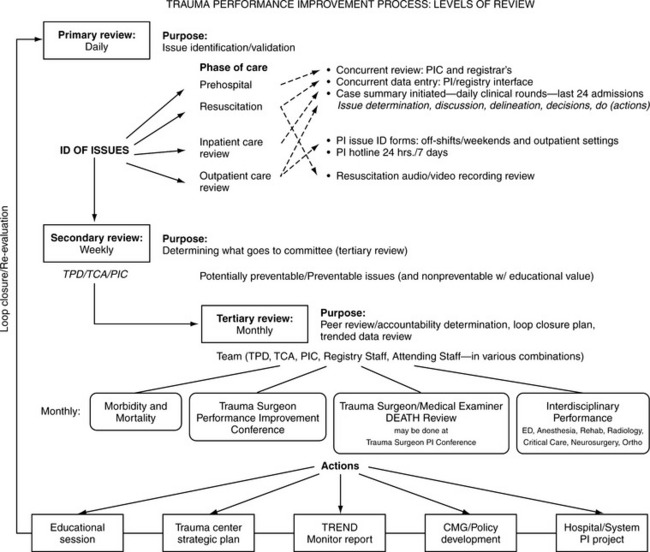

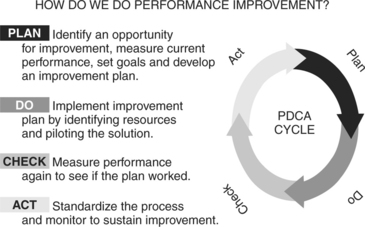

The terms and principles related to quality have gone through many changes in recent times. “Quality assurance,” “quality improvement,” “continuous quality improvement,” “total quality management,” and “performance improvement” are all approaches to quality review that have been used in the past.2 A major conceptual shift in these approaches has been the movement from a punitive quality assurance model to the more accepted system/process review. In addition, performance improvement in health care settings is being more closely integrated with patient safety. The health care industry continues to evolve its methodology for quality review, and the days of the “ABCs” of morbidity and mortality (accuse, blame, and criticize) are fading. This system/process performance improvement model is focused on outcomes, benchmarking, and performance of the system as a whole and moves away from emphasis on reviewing an individual’s practice as a root cause. There must, however, also be a structured physician peer review process to evaluate clinical competency. Traditionally, hospital performance improvement and quality improvement have been service-line or unit specific. Depending on the institution, specific performance or quality committees would develop and implement projects, quite often following The Joint Commission (formerly known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]) format, the performance improvement cycle (Figure 3-1). In the trauma care arena, there are standards that outline the basic type of performance review that trauma centers need to complete. Included in these standards are recommendations for performance indicators (including definitions) that should be monitored over time. Because of the strict standards set forth by trauma center accrediting agencies, often it is the trauma program that leads performance improvement efforts in hospitals.

FIGURE 3-1 Performance improvement cycle.

(From The Joint Commission: Joint Commission accreditation manual, Oakbrook Terrace, Ill, 1998, The Joint Commission.)

Health care practitioners struggle to understand and operationalize the concepts of what we now call performance improvement. The popular literature on quality, which includes the works of pioneers such as Juran and Deming, is focused on industrial settings. W. E. Deming, considered one of the leading figures in the movement to measure quality in industry, developed theories that are widely published. His work has been applied to multiple venues outside the traditional business world, including health care. Out of the Crisis (1986),3 considered one of Deming’s major works, provides anecdotes and examples of how to put his theories into practice.

A particular challenge to health care practitioners is determining how to apply techniques and principles designed for more “constant” industrial environments to the unpredictable and dynamic practice of medicine. One example of a methodology that was initially developed for manufacturing and that has been applied to health care is Six Sigma. This is a structured format that uses reliable and valid data and statistics to improve performance by identifying and eliminating variations or “defects” in processes.4 The current environment in health care has presented additional challenges in the quest to operationalize performance improvement. Human and financial resources are lean and patient demographics are changing. To our advantage, however, are modern technologic advancements and the power of computerization in the maintenance and analysis of patient data.

PATIENT SAFETY

The Joint Commission oversees the development and annual updating of the National Patient Safety Goals and Requirements. This process is overseen by an expert panel that includes a multidisciplinary team including patient safety experts, nurses, physicians, pharmacists, risk managers, and other professionals who have hands-on experience in addressing patient safety issues in a wide variety of health care settings. Trauma programs, with mature performance improvement programs, have traditionally provided a model approach to monitoring potentially high-risk events and ensuring a review of cases where defined risk criteria are present. The ACS in the 2006 edition of Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient, has recognized that performance improvement and patient safety are intricately linked and should be approached in unison. The patient safety process is focused on the environment in which care is given and the performance improvement process is directed at the care provided. The boundaries between these two often cross over and in many cases are indistinguishable.

A number of topics central to the delivery of trauma care provide excellent examples of practical links between patient safety and performance improvement. Some of the past patient safety goals set forth by The Joint Commission, such as patient identification, right site surgery, medication safety, and communications/handoffs are particularly relevant to trauma care delivery. Each of these presents unique challenges to the trauma program. Given the rapidity of the initial evaluation, the routine need for urgent surgery, and the issues related to workforce shortages, all these Joint Commission safety goals are reasonable focus points in the trauma performance improvement program.5

TRAUMA PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT PLAN

• Overview of the process—issue identification

• Personnel involved and their roles

• Performance improvement forums/committees

• Link to hospital/system performance improvement

• Performance indicators (dynamic)/patient safety goals

• Guidelines for determining peer review judgment decisions (accountability)

• Performance improvement reports/provider profiles

• Performance improvement loop closure (reevaluation)

The performance improvement plan should consider state, regional, and national standards related to trauma care. The ACS document titled Trauma Performance Improvement, A How to Handbook provides practitioners with an operational manual for establishing and maintaining a trauma performance improvement program.6 In addition, programs such as the Society of Trauma Nurses Trauma Outcomes Performance Improvement Course “T.O.P.I.C.” assist practitioners with developing a comprehensive trauma performance improvement plan and provides practical approaches to operationalizing performance improvement in all levels of trauma centers.7

INTEGRATION OF TRAUMA PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT WITH INSTITUTION AND SYSTEM PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT

Trauma programs lead the way in many institutions in terms of the depth, scope, and sophistication of performance improvement reviews. It is important that trauma programs be integrated into the overall hospital or system quality structure. Many health care organizations have adopted service-line teams to oversee performance improvement–related projects. Trauma crosses over and affects many service lines of the hospital structure, including nursing, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, anesthesia, orthopedics, rehabilitation services, radiology, laboratory services, perioperative care, critical care, nutrition, and the blood bank. It is challenging to devise a single initiative that coordinates the activities of the multiple service lines through which care is provided to trauma patients. There must be some means of overseeing continuing projects and determining areas of overlap, mutual benefit, and level of impact. For example, many hospitals collect intensive care unit (ICU) data; these data could be stratified to look at trends specifically within the trauma patient group. Conversely, data maintained by the trauma program may be stratified by phases of care and reported through the hospital performance improvement structure. Analysis of various levels of data from hospital departments can generate specific institutional projects. Projects that have the highest return on investment should be selected. Projects that target key areas or have strong potential to affect outcomes, patient satisfaction, or cost should be prioritized.

• Conducting a thorough and credible root cause analysis, focusing on systems and processes, not individual performance

• Implementing improvements to reduce risk

Two useful techniques for analyzing unexpected outcomes are (1) FMECA (failure mode, effect, and criticality analysis), which is a systematic way to examine a process for possible ways that failure can occur, usually initiated by a “near miss” incident, and (2) root cause analysis, which looks for the cause of variation after a sentinel event or unexpected outcome has taken place.8,9 Regardless of the analysis technique used, benchmarking with other similar centers provides meaningful perspective for trauma programs.

PATIENT/ISSUE IDENTIFICATION

• Physician documentation on progress notes or consultation records

• Perioperative records, including anesthesia notes and postanesthesia care notes

• Radiology and laboratory reports

• Physical and occupational therapy notes

• Social work, pastoral care, or case management notes

• Transfer records for patients referred from another facility

Other departments in the hospital may be a source of information regarding performance improvement issues. Infectious disease reports can identify patients with complications such as urinary tract infections or pneumonia, supporting or validating trauma performance improvement data. Postdischarge records are a source of information regarding outcomes because they may identify missed injuries, delayed diagnoses, readmissions, or patient satisfaction issues. It is important that there are processes to identify and report performance improvement issues in the trauma outpatient arena. Postdischarge information can be obtained from outpatient records, feedback from rehabilitation facilities, follow-up from home care agencies, or autopsy reports. The medical examiner or coroner can often provide additional valuable data at mortality review forums. This can be achieved through direct participation of medical examiner staff or through the retrospective review of written or verbal autopsy reports.

TRAUMA PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT PROCESS: LEVELS OF REVIEW

There are many ways to structure a review of clinical care. Having both concurrent and retrospective features is ideal. Key steps should be established and should be modified on the basis of the specific features of the trauma program (size, volume, resources, etc.). Key elements in the performance improvement process are diagrammed in Figure 3-2.

PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT FORUMS

CASE SELECTION GUIDELINES FOR TERTIARY REVIEW

A key component of the performance improvement process is the provision of a peer review forum to discuss individual cases, trends in data, and comparative data related to system performance. Peer review forums should involve key trauma program/hospital staff (Table 3-1). Hospital/medical staff bylaws may dictate attendance at physician peer review sessions. These should be considered when determining the structure for peer review forums. Performance improvement committees can be structured in a variety of ways depending on the resources available, the volume of cases, and the local, state, and regional rules related to performance improvement reviews.

TABLE 3-1 Performance Improvement Roles of Trauma Program Staff in a Level I Trauma Program