57

Percutaneous Treatment of Proximal Pole Scaphoid Fractures

Joseph F. Slade III and John D. Mahoney

History and Clinical Presentation

A 20-year-old male college football player sustained a hyperextension injury to his wrist after a fall during practice. He initially had radiographs taken, and his injury was diagnosed as a sprain and was splinted for 2 weeks. He was referred to the hand clinic for evaluation and treatment.

Physical Examination

The patient complains of pain at the base of his thumb, and locates pain to the region of the snuffbox. There is minimal swelling noted, and range of motion is decreased when compared with the opposite wrist. There is point tenderness over the proximal pole of the scaphoid. There is no carpal or wrist instability (Shuck test evaluating lunate-triquetrum, scaphoid shift test for scapholunate instability, and ballottement test for distal radioulnar joint are all negative).

Diagnostic Studies

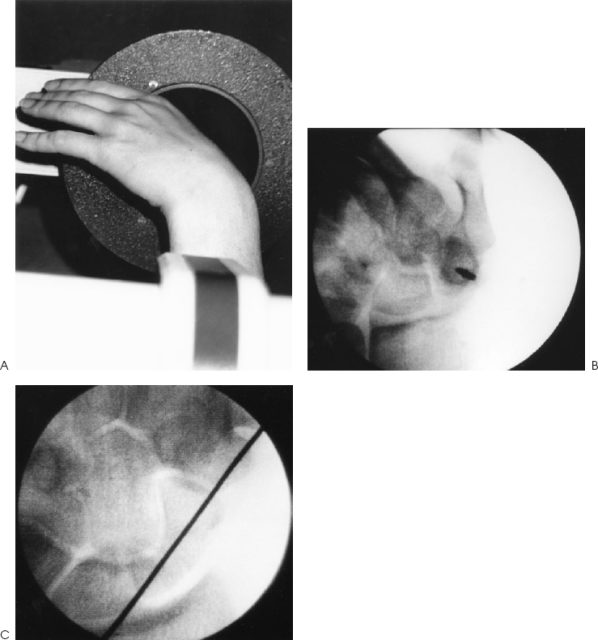

Initial radiographs included three standard films of the wrist: a posteroanterior (PA) view of the wrist with the forearm in a neutral position, a lateral projection of the wrist, and an oblique view with the forearm in 35 degrees of supination. These films were negative. Follow-up serial films at 4 weeks demonstrated a fracture of the proximal pole of the scaphoid (Fig. 57–1).

Figure 57–1. Posteroranterior view of the hand showing acute proximal pole scaphoid fracture.

PEARLS

- The plain radiographic appearance of a scaphoid fracture is often a poor predictor of operative findings. Green suggested the best indicator of proximal viability is punctate bleeding in the operating room. The postoperative management of scaphoid fractures should include serial CT scans to confirm reduction and identify bridging callus of a healing fracture.

- Stable fixation with a minimally invasive procedure will allow earlier return of function and better long-term outcome.

- Relative ischemia of the proximal pole is not a contraindication to internal fixation. Stable union will permit revascularization.

PITFALLS

- Interval radiographs of less than 6 months should not be used for analysis of union.

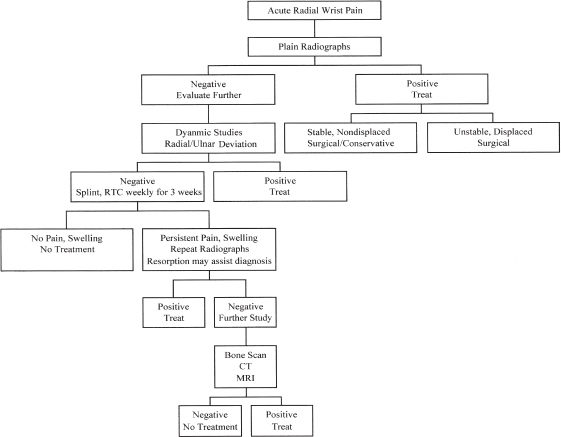

Figure 57–2. Evaluation of acute radial-sided wrist pain.

The diagnosis of scaphoid fracture is often not straightforward. We have developed an algorithm for the radiographic evaluation of radial wrist pain (Fig. 57–2). Initial evaluation includes the standard set of radiographs. Follow-up of initial studies is demanded for persistent pain. Resorption of bone at follow-up will aid in fracture detection. A bone scan taken 2 to 3 weeks after injury is highly sensitive for fracture or ligamentous injury. A negative scan excludes a fracture. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are highly specific and sensitive for detection of a scaphoid fracture.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis and appropriate studies for each possibility are presented in Table 57–1.

| Suspected Injury | Diagnostic Studies |

| Scaphoid fracture | As described |

| Scaphoid-lunate ligament tear | Clenched fist radiographs, arthrogram, cineradiography, bone scan |

| Distal radius styloid fracture | Standard radiographs, CT scan, and bone scan |

| Lunate dislocation | Lateral wrist radiographs, CT scan |

| Lunate-triquetral ligament tear | Clenched fist radiographs, arthrogram, cineradiography, bone scan |

| Avascular necrosis of the lunate or scaphoid | MRI |

| Other carpal bone fractures | Radiographs, CT scan, and bone scan |

| Combination of above injuries | Appropriate combination of studies, as above |

Diagnosis

Fracture of the Proximal Pole of the Scaphoid (Herbert B3)

Scaphoid fractures are the most common fracture of the carpus (80% of total), and of the wrist, the second most common after fractures of the distal radius. The typical patient is a young man injured after a fall on an extended wrist. Diagnosis of fracture is suggested by the patient’s age, mechanism of injury, and symptoms. Radiographs are required to confirm diagnosis.

The scaphoid bone is anatomically unique. First, its blood supply from the superficial palmar branch of the radial artery and the dorsal carpal branch of the radial artery runs from distal to proximal, with the proximal pole receiving the most tenuous blood supply. Thus, the proximal pole is particularly susceptible to avascular necrosis as a complication of fracture. Second, its irregular three-dimensional shape presents special problems in diagnosis of acute fractures and their treatment. It is an intraarticular bone, with 80% of its surface covered with articular cartilage. Displaced fractures result in early degenerative arthritis, and malunions can lead to carpal collapse.

The scaphoid is most commonly fractured across its middle third, with 70% of fractures across the “waist.” Ten percent are distal third fractures, and 20% are proximal third fractures. All proximal pole fractures should be considered unstable regardless of radiographic appearance. Russe classified scaphoid fractures into three categories based on the fracture axis: horizontal oblique, transverse, and vertical oblique. Horizontal oblique and transverse fractures together comprise ∼95% of fractures, and respond equally well to therapy. Vertical oblique fractures comprise the remaining 5%, and they tend to have a slower progress to union and a higher rate of nonunion.

Optimum treatment depends on diagnosing a fracture acutely and the correct classification of the injury. CT scans greatly assist in classifying these injuries and in assessing displacement and angulation. CT scans are most useful for determining fracture union. The Herbert classification scheme for scaphoid fractures uses radiographic appearance to determine surgical versus nonsurgical management (Table 57–2). Nonsurgical management is reserved for Herbert type A fractures.

Surgical Management

A contralateral radiograph of the normal scaphoid was taken to determine screw length. A CT scan confirmed proximal pole fracture, nondisplaced. Seven weeks after the initial injury, the patient was taken to the operating room for definitive management. The wrist was flexed to 90 degrees with the forearm pronated until the scaphoid was viewed down its long axis as a ring of cortical bone (Fig. 57–3). In the center of the ring, a 0.045-inch Kirschner wire (K wire) was driven from proximal to distal (dorsal wrist), exiting at the base of the thumb. From the base of the thumb (distal), the wire was withdrawn to the point that the wrist can again be extended to a neutral position. The hand and forearm were exsanguinated, and a tourniquet was used to maintain a bloodless field. The fingers are placed in finger traps, and longitudinal traction is applied (12 to 15 lb).

| Type | Description |

| Type A | Acute, stable fractures; conservative management possible |

| A1 | Fracture of tubercle |

| A2 | Incomplete fracture through waist |

| Type B | Acute, unstable fractures; surgical management required |

| B1 | Distal pole oblique fracture |

| B2 | Complete fracture of waist |

| B3 | Proximal pole fracture |

| B4 | Transscaphoid-perilunate fracture-dislocation of the carpus |

| Type C | Classification no longer used; included delayed union; now part of type D |

| Type D | All nonunions older than 6 weeks |