Pelvis

Andrew S. Sems

POSTERIOR APPROACH TO THE SACRUM AND SACROILIAC JOINT

Indications

Open reduction and internal fixation of sacral fractures.

Open reduction and internal fixation of sacroiliac fracture-dislocations.

Open reduction and internal fixation of sacroiliac dislocations.

Open reduction and internal fixation of sacroiliac dislocations with iliac fractures (crescent fracture).

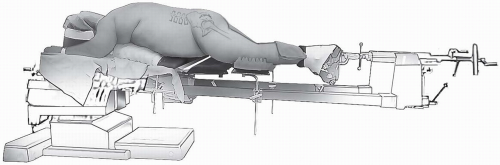

Position

The patient is placed in the prone position with chest rolls positioned to allow the abdomen to hang free (Fig. 6-1). A completely radiolucent table is utilized to allow imaging in multiple planes including Judet views and inlet and outlet views. The chest roll should be placed proximal enough so that the pelvis actually hangs free, as this is helpful in assisting in obtaining reduction of these fractures. By supporting the patient’s thorax rather than directly on the anterior pelvis, the axial skeleton will be stabilized proximally, allowing the hemipelvis to hang free and reduce anteriorly.

Landmarks

The posterior-superior iliac spine as well as the entire iliac crest should be palpated. The spinous processes of the sacrum and lumbar vertebrae should be identified.

Technique

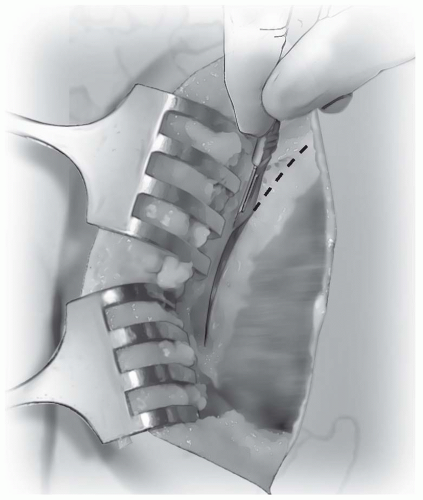

Incision: the incision is longitudinal in direction (Fig. 6-2). It can be translated medially or laterally as appropriate for the particular type of fracture. For sacral fractures, a more medially based incision is appropriate, whereas for crescent type fractures or pure sacroiliac dislocations, the incision can be made based more laterally. For a crescent fracture or sacroiliac dislocation, the incision

should be just lateral to the posterior-superior iliac spine. It may be curved laterally as it can fall in line with the iliac crest as it travels anteriorly and laterally. However, a vertical incision also can be useful to gain full exposure. In thinner patients, an incision directly over the posterior-superior iliac spine should be avoided, as the subcutaneous location of the bony prominence may cause difficulty with wound healing and breakdown.

Note: Injection of lidocaine and epinephrine mixtures into the surgical site before making the skin incision can assist in controlling bleeding in the area. There is often a large amount of subcutaneous adipose in this region with significant vascularity that can bleed throughout the case and cause exposure and visualization to be difficult, so careful attention to gaining hemostasis throughout the subcutaneous dissection is important.

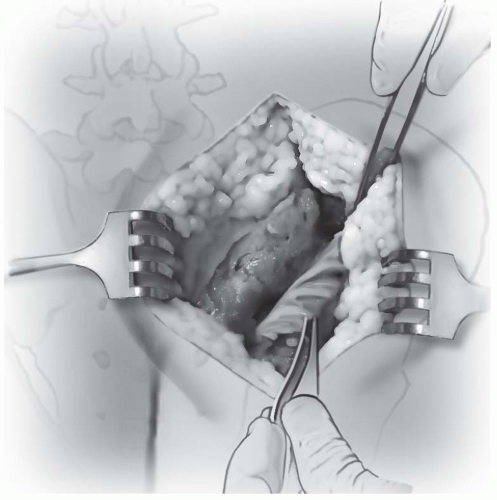

The gluteus maximus is identified as it inserts onto the posterior-superior iliac spine and iliac crest. It is incised in the tendinous portion along the posterior-superior iliac spine, leaving a cuff of tissue on the posterior-superior iliac spine for later repair (Fig. 6-3).

As the dissection extends posteriorly, the gluteal tendon is incised toward the midline over the sacrum. This allows complete retraction of the gluteus maximus and exposure of the posterior-superior iliac spine as well as the posterior aspect of the ilium. Care should be taken to not disturb the underlying paraspinal muscles, particularly the multifidus, unless dissection onto the sacrum is necessary. For most sacroiliac dislocations and crescent fractures, these paraspinal muscles can be left undisturbed. For sacral fractures, the injury and initial displacement of the

fracture has often caused severe injury to the paraspinal muscles and some local debridement during the approach may be all that is necessary in order to fully visualize the fracture.

The gluteus maximus is elevated subperiosteally along the posterior aspect of the ilium distally to the greater sciatic notch, giving access to the entire crescent fracture and sacroiliac joint (Fig. 6-4).

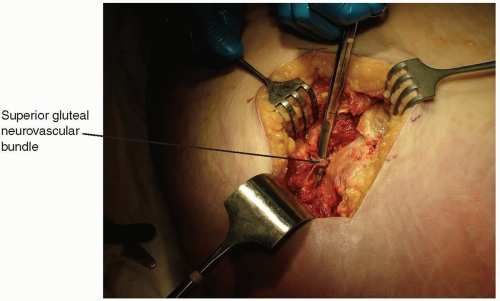

Finger palpation beneath the greater sciatic notch can be utilized to assess anterior reduction of a sacroiliac dislocation. Exposure of the greater sciatic notch will allow placement of a reduction clamp to correct the vertical displacement of the hemipelvis that occurs in posterior pelvic ring injuries. Care should be taken during dissection into the greater sciatic notch to protect the sciatic nerve as well as the superior gluteal vessels and nerve (Fig. 6-5).

Once reduction and fixation of the posterior ring is completed, care should be taken to repair the gluteus maximus insertion in its tendinous portion using a heavy permanent suture such as 0-Ethibon. Subcutaneous tissue should be closed in multiple layers as well, and drain placement is recommended depending on the amount of hemorrhage encountered.

FIGURE 6-2 The posterior incision can be either curved or vertical in nature depending on the exact location of the fracture. |

FIGURE 6-4 The gluteus maximus is retracted laterally away from the sacroiliac joint and can be retracted as far as the greater sciatic notch. |

FIGURE 6-5 The superior gluteal neurovascular bundle prevents further lateral retraction of the gluteus maximus. |

Pearls and Pitfalls

Avoid making an incision directly over the most prominent portion of the posterior-superior iliac spine, particularly in thinner patients as this may be very prominent and may break down as the patient lies on their back recovering.

Subperiosteal dissection along the lateral aspect of the ilium can identify the proximal extent of crescent fractures. Blunt retractors or malleable retractors along the lateral aspect of the ilium can be utilized to visualize these fractures and gain anatomic reduction. Additionally, sacroiliac screws may provide a large amount of stability to a fixation construct for sacroiliac dislocations and crescent fractures. These screws should be placed away from the iliac fracture line so they will not fail by breaking through into the fracture site, and this can be visualized through this approach. However, percutaneous incisions will need to be made over the lateral aspect of the gluteal region in order to place the screws, as the necessary trajectory cannot be obtained through the posterior approach to the sacroiliac joint.

APPROACH TO THE ACETABULUM THROUGH THE ILIOINGUINAL APPROACH

Indications

Both column fractures of the acetabulum.

Anterior column posterior hemi-transverse fractures of the acetabulum.

Anterior column fractures.

In conjunction with the Kocher-Langenbeck approach for treatment and fixation of transverse, and T-type acetabular fractures.

Position

The patient is positioned supine on a radiolucent table (Fig. 6-6). Traction is often utilized before reduction of these cases and a table such as a Judet-Tasserit table or Pro FX fracture table which is radiolucent and allows the use of traction in multiple directions is optimal.

Landmarks

One should palpate the entire iliac crest as well as paying attention to the anterior-superior iliac spine. The pubic tubercles and symphysis should be identified.

Technique

Incision: the incision follows the contour of the iliac crest from posterior to anterior, and then is directed over the inguinal ligament to a point approximately 2 cm proximal to the pubic symphysis (Fig. 6-7).

The abdominal musculature is identified as it inserts on the iliac crest. The aponeurosis of the abdominal muscles terminates just proximal to an avascular zone between the hip abductors and abdominal musculature. This zone is identified and this interval should be split directly down to the iliac crest (Fig. 6-8).

Subperiosteal dissection along the iliac crest with elevation of the abdominal musculature insertion is performed to gain access to the inner table of the pelvis, exposing the lateral window. Once the lateral window has been exposed and the iliopsoas has been elevated off the inner fossa, this area of the wound should be packed with lap sponges and the exposure should continue distally.

The skin incision is then extended from the anterior-superior iliac spine to an area approximately 2 cm proximal to the pubic symphysis.

The external abdominal oblique musculature and fascia is identified as the fibers course in a direction from superolateral to inferomedial towards the superficial inguinal ring. The spermatic cord should be identified and a Penrose drain should be placed around it to protect it and allow retraction medially and laterally (Fig. 6-9).

The external abdominal oblique is split in line with its fibers just proximal to its insertion on the inguinal ligament (Fig. 6-10). Dissection should be continued down towards the inferior aspect of the superficial inguinal ring. If possible the superficial ring should be kept in place so that a later repair is not necessary.

At this point the combined tendon of the internal abdominal oblique and transverse abdominus muscle is identified as it inserts on the inguinal ligament. This conjoined tendon should be incised in line with its fibers near its insertion on the inguinal ligament giving ample amount of tendon on both sides of the incision to repair at the end of the case (Fig. 6-11).

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is identified crossing over the psoas muscle near the anterior-superior iliac spine. This nerve may need to be sacrificed for complete exposure of the acetabulum; however, initial attempts should be made to protect and save this nerve.

The psoas muscle and femoral nerve should be identified. These structures should be kept together and a Penrose drain should be placed around them in their entirety (Fig. 6-12). Care should be taken to elevate the psoas off of the internal fossa of the ilium in its entirety so that trauma to the muscle is minimized.

Once the entire psoas muscle and femoral nerve are protected with a Penrose drain, they can be retracted laterally. The iliopectineal fascia is identified and very careful dissection just medial

to this should be performed to separate it from the external iliac vessels. Once the iliopectineal fascia is separated from the external iliac vessels, a finger should be placed between the fascia and the vessels to palpate the pulse and confirm the vessels are medial to the finger.

Once the external iliac vessels are confirmed to be medial and the fascia is isolated, scissors are used to split the iliopectineal fascia all the way to the pelvic brim (Fig. 6-13).

With the combined tendon of the transversalis abdominus and internal abdominal oblique incised near its insertion, dissection should now proceed medially. A small portion of the rectus abdominus muscle will need to be incised transversely as it inserts on the pubic tubercle just medial to the spermatic cord or round ligament (Fig. 6-14). This will allow for exposure of the medial side of the external iliac vessels.

Circumferential access to the external iliac vessels can now be gained by placing a Penrose drain around the bundle and it can now be retracted medially and laterally (Fig. 6-15).

Once this is performed, all three windows of the ilioinguinal approach have been exposed and reduction and fixation of the acetabular fracture can be performed.

Following fixation, care should be taken to tightly repair the structures in the inguinal region to prevent postoperative hernia development. After thorough irritation of the wound, the portion of the transected rectus abdominus is reapproximated using interrupted 0-Ethibon sutures. Next, the internal abdominal oblique and transversalis abdominus conjoined tendon is repaired back to the inguinal ligament using multiple 0-Ethibon sutures.

Note: Multiple single sutures are preferred in case one should break or rupture, the remainder of the repair will stay intact.

A layered closure is preferred and the external abdominal oblique is then closed using 0-Ethibon sutures. If care has been taken during the dissection to preserve the superficial inguinal ring, the fascia can typically be closed just below this and the ring will be intact.

A drain can be placed in the lateral aspect of the wound, resting in the internal iliac fossa. The abdominal aponeurosis can then be reapproximated using multiple 0-Ethibon sutures. The subcutaneous tissue is closed in layers and the skin is closed with either a nonabsorbable monofilament suture or a staple.