Pelvic Osteotomies for Hip Dysplasia

Robert T. Trousdale

Key Points

Introduction

Reorientation pelvic osteotomy is the treatment of choice for young patients with symptomatic structural disorders of the acetabulum in the absence of severe secondary changes.1 These structural problems can be grouped into three categories: classic developmental dysplasia, retrotorsional abnormalities of the acetabulum, and post-traumatic problems. During the past 20 years, various techniques of acetabular reorientation have evolved, making the procedure relatively reliable, reproducible, and durable. Many patients who present with hip pain are not good candidates for arthroplasty because of their young age and limited activity level; some often have reasonable articular cartilage present.

Patients with classic developmental hip dysplasia typically have varying degrees of anatomic abnormalities.2 On the acetabular side, the joint socket usually is shallow, anteverted, and lateralized, and femoral head coverage is deficient anteriorly and superiorly. The versional status of the acetabulum may be retrotorted in up to 25% of the acetabula. On the femoral side, the head can be small, the neck shaft angle is typically increased, and the femoral canal is narrow. These structural abnormalities lead to decreased contact between the femoral head and the acetabulum and an increased body weight lever arm from excessive lateralization of the hip center of rotation. Relatively high forces transmitted through this decreased surface area can lead to secondary degenerative joint disease over time.

In young patients with symptomatic hip dysplasia with viable articular cartilage, reorientation of the acetabulum is the procedure of choice. Pelvic osteotomy increases the hip contact area and allows for medialization of the hip center of rotation, which decreases the body weight lever arm. These improvements in the mechanics about the hip joint are expected to reduce pain and protect the articular cartilage from further degenerative changes.

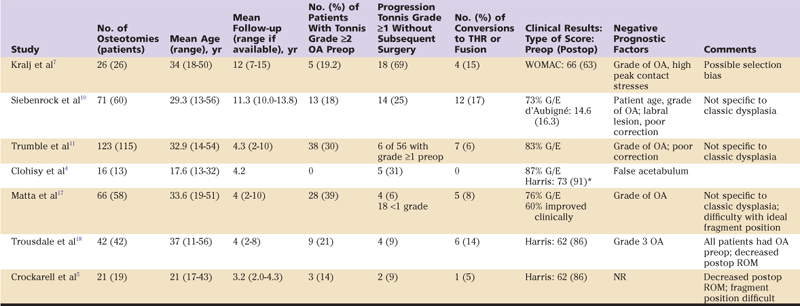

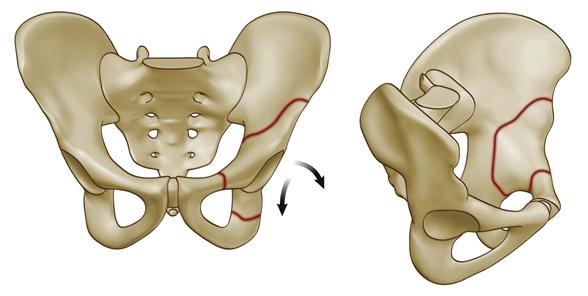

Many types of pelvic osteotomies have been described.1 Single, double, triple, and various periacetabular osteotomies improve mechanics about the hip joint. Each technique has advantages and disadvantages. The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy developed by Ganz and others3 in the early 1980s is currently the acetabular procedure of choice in many centers (Table 56-1). It has many advantages: It can be done through one incision through a series of straight, reproducible, extra-articular osteotomies. It allows for large corrections in all necessary directions. The osteotomy is inherently stable because the posterior column of the hemipelvis remains intact, and the orthogonal cuts render some stability to the fragment once it has been mobilized. In addition, minimal internal fixation is required. No casting or bracing is needed, and early ambulation is possible. The vascularity of the acetabular fragment via the inferior gluteal artery is preserved, and an arthrotomy can be done without further risk of devascularization of the osteotomized fragment. The shape of the true pelvis is not markedly changed, allowing women who become pregnant after the procedure to have a vaginal delivery. Furthermore, the procedure can be done without taking down the abductors, which facilitates a relatively rapid recovery (Fig. 56-1).4–11

Table 56-1

Results of Periacetabular Osteotomy for Dysplastic Hips

G/E, Good/excellent; NR, not reported; OA, osteoarthritis; postop, postoperatively; preop, preoperatively; ROM, range of motion; THR, total hip replacement; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index.

Figure 56-1 The location of bone cuts for a Bernese periacetabular osteotomy.

Indications/Contraindications

Reorientation pelvic osteotomy may be offered to young patients with symptomatic hip dysplasia without excessive proximal migration of the hip center of rotation and with no more than mild to moderate degenerative changes of the articular surface. Because most of the structural abnormality is located on the acetabular side of the joint, correction is best attained with a pelvic osteotomy.12,18 Joint congruity also is important. Having a relatively round acetabulum that matches a relatively round femoral head probably produces a more reliable and durable outcome. Examination of the hip under fluoroscopy and functional radiographs can be helpful in ensuring that reasonable joint congruity is present. The extent of acceptable secondary arthrosis or incongruity depends in part on the patient’s age and expectations, and on potential future demands that will be placed on the hip joint.13 A Chiari osteotomy, a shelf osteotomy, and arthroplasty are reasonable options when congruity or arthrosis makes the success of a reconstructive osteotomy unlikely.

Surgical Technique

Regional epidural anesthesia is used in most patients. We have abandoned the use of preoperative autologous blood donation because intraoperative cell saver appears quite helpful in minimizing the need for allogeneic blood. Presently, the allogeneic transfusion rate at our institution is less than one in four patients.

The patient is placed on an image table, and an indwelling urinary catheter is inserted. The sciatic and femoral nerves are monitored with intraoperative electromyography to minimize the chance of neurologic injury14,15 (Fig. 56-2). Beginning in 1992, we used an anterior incision, which provided exposure by the inner and outer tables of the pelvis. Four years later, we began to use the same skin incision to perform the osteotomy while exposing only the inner aspect of the pelvis, leaving the abductors intact on the outer aspect of the ilium.16,17 This approach has dramatically improved the rate of healing, time to weight bearing, and resolution of the postoperative limp.

Figure 56-2 Intraoperative photograph showing preparation with fluoroscopy and electromyographic (EMG) monitoring.

The incision typically begins along the border of the iliac crest, proceeds along the anterosuperior iliac spine, and continues distally, ending approximately 3 cm distal and anterior to the greater trochanter19 (Fig. 56-3). The plane between the tensor fascia lata and the sartorius is then developed, and the deep fascia over the tensor fascia lata is incised to avoid direct injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. The sartorius origin is reflected from the anterosuperior iliac spine. The hip is then flexed and adducted, and the inner table of the pelvis is exposed to the sciatic notch. The pubis is exposed by retracting the iliopsoas tendon medially. The direct head of the rectus is reflected distally from the anteroinferior iliac spine, exposing the anterior hip capsule. Blunt dissection then proceeds distally and medially, and under an image intensifier, a scissors is used to palpate the ischium and the obturator foramen.

Figure 56-3 Intraoperative photograph showing the location of a skin incision on the patient’s left hip.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree