Wayne G. Paprosky

Pelvic Discontinuity

TREATMENT OF PELVIC DISCONTINUITY WITH PELVIC STABILIZATION USING INTERNAL FIXATION

TREATMENT OF PELVIC DISCONTINUITY USING PELVIC DISTRACTION

INTRODUCTION

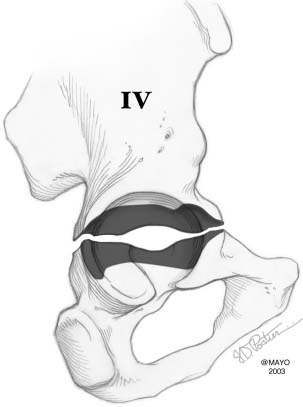

Pelvic discontinuity and pelvic dissociation are synonymous terms, both of which denote a circumstance in which the superior hemipelvis has become disconnected from the inferior hemipelvis due to bone loss, fracture, or most commonly, a combination of the two (Fig. 17-1). Rarely, pelvic discontinuity occurs in association with other fractures that separate the inferior pelvis into separate, anterior and posterior pieces (essentially a T- or Y-shaped acetabular fracture) (Fig. 17-2).

FIGURE 17-1. Pelvic discontinuity, also known as pelvic dissociation, represents complete discontinuity of the superior hemipelvis from the inferior hemipelvis due to bone deficiency, fracture, or in most cases, a combination of the two. (By permission of Mayo Foundation for Medial Education and Research. All rights reserved.)

FIGURE 17-2. Radiograph of the patient with Y-shaped pelvic discontinuity. Note the ischium is separated from the rest of the pelvis as a separate fragment.

Pelvic discontinuity usually occurs due to a chronic nonunited pelvic stress fracture through deficient bone in the revision arthroplasty setting; however, pelvic discontinuity also may be present due to an acute acetabular fracture during total hip arthroplasty, or a nonhealed acetabular fracture.

Pelvic discontinuity poses the dual difficulties of a nonunited fracture and acetabular bone loss, which together make successful treatment of these problems among the most challenging in revision hip surgery.1–6

CLASSIFICATION

Pelvic discontinuity is classified as Type IV pelvic deficiency in the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Acetabular Bone Classification.7 Pelvic discontinuity has been further subcategorized as Type IVA when it occurs in the presence of mild or moderate acetabular bone loss, Type IVB deficiency when it occurs in the presence of severe pelvic bone loss, and Type IVC when it occurs in the presence of previous therapeutic pelvic irradiation.1

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Pelvic discontinuity is relatively uncommon—in 3,505 acetabular revisions at the Mayo Clinic, it was identified in 31 cases (0.9%).8 Pelvic discontinuity is more common in women (28 of 31 hips in the Mayo series, p < 0.0001), probably in part because the smaller pelvis is at greater risk of stress fracture and in part because lower bone mineral density predisposes to stress fractures. Pelvic discontinuity occurs more commonly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and also in patients with previous therapeutic pelvic radiation. Pelvic radiation reduces the remodeling and healing potential of pelvic bone.

IDENTIFICATION

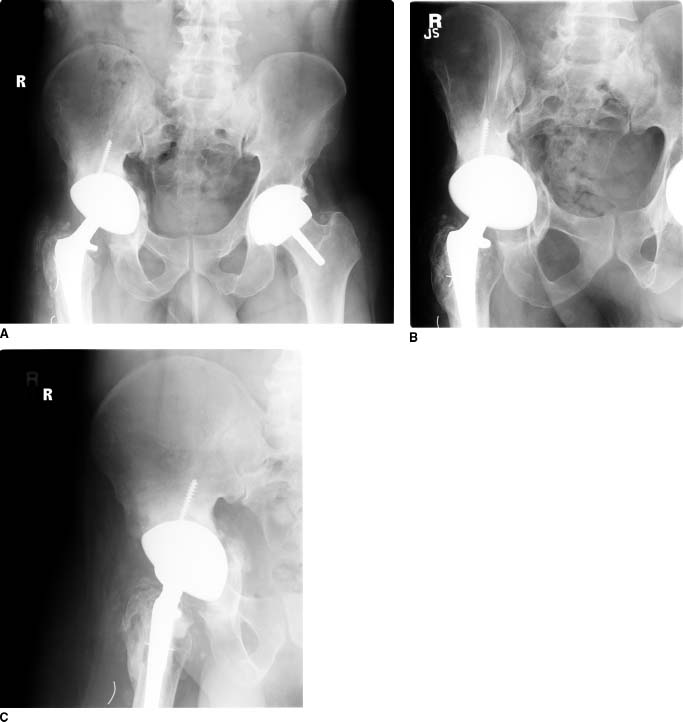

Pelvic discontinuity usually can be identified on preoperative plain radiographs (Fig. 17-3). When suspected but not clearly evident, Judet views (45-degree oblique views) of the pelvis can help demonstrate pelvic discontinuity (Fig. 17-4). However, not all pelvic discontinuities can be recognized on plain radiographs because the discontinuity fracture line may be obscured by the acetabular component or cement. Computed tomography scans with three-dimensional reconstruction may detect pelvic discontinuity not visible on plain films.

FIGURE 17-3. Radiograph of the patient with right pelvic discontinuity. Note the triad of findings: (i) visible transverse fracture line, (ii) break in Kohler line, and (iii) rotation of the inferior hemipelvis. Not all cases demonstrate these classic findings.

FIGURE 17-4. A: AP radiograph of a patient demonstrating possible right pelvic discontinuity. B and C: Judet 45-degree oblique pelvic films definitively demonstrate pelvic discontinuity with visible fracture lines through anterior column (B) and posterior column (C).

A triad of radiographic findings have been associated with pelvic discontinuity: (i) visible transverse acetabular fracture, (ii) transverse offset of the inferior pelvis relative to the superior pelvis, and (iii) rotation of the inferior pelvis relative to the superior pelvis (Fig. 17-3).1,9 Sometimes it is difficult to differentiate a fracture involving only the medial wall of the acetabulum from a true pelvic discontinuity. Fracture through the posterior column often is best seen on Judet views or on a true lateral radiograph of the pelvis. On a well-centered anteroposterior [AP] pelvic radiograph, transverse offset of the pelvis is seen as a discontinuity of Kohler line, typically with the inferior pelvis translated medially relative to the superior pelvis. On a well-centered AP pelvic radiograph, rotation of the inferior hemipelvis is seen as asymmetry of the obturator foramen on one side compared to the obturator foramen on the opposite side.

Intraoperative identification of pelvic discontinuity is straightforward only if the fracture is quite mobile (Fig. 17-5). Frequently, the findings are subtle and the discontinuity can only be confirmed by manipulating the ischium anteriorly and posteriorly with a robust instrument, thereby demonstrating motion along the fracture line.

FIGURE 17-5. Intraoperative photograph demonstrating pelvic discontinuity with fracture line through the anterior and posterior columns, and medial wall of the acetabulum. Often the fracture line is difficult to see.

TREATMENT OF PELVIC DISCONTINUITY WITH PELVIC STABILIZATION USING INTERNAL FIXATION

Treatment of pelvic discontinuity remains one of the most challenging and difficult problems in revision total hip arthroplasty. Tenants of pelvic discontinuity treatment include (a) pelvic stabilization, (b) management of bone loss, (c) placement of a stable acetabular component, and (d) bone grafting of the pelvic discontinuity. Most revision surgeons believe that gaining rigid stability of the pelvis provides the greatest chance of pelvic healing. However, obtaining healing of pelvic discontinuity is challenging because of the poor bone quality and poor vascularity, bone loss, and the thin bone surfaces available for contact.

INTERNAL FIXATION METHOD

A posterior column plate can provide satisfactory stability to provide for pelvic healing in many cases. An additional anterior column plate usually is not necessary, although one can be added through an ilioinguinal or Stoppa approach if required.

Posterior column plating requires excellent exposure of the posterior column, which can be obtained through a posterior or a transtrochanteric approach. The sciatic nerve location must be ascertained so that it can be protected during this procedure, because it is frequently adherent to the discontinuity site and may be encased in scar tissue. The nerve can be identified distally by dividing the gluteus maximus tendon and then finding the nerve in the fat deep to the tendon. The nerve then can be traced proximally. Once the sciatic nerve is carefully protected, soft tissues are taken down from the posterior wall

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree