29 PEDIATRIC TRAUMA

Trauma is the leading cause of death in children from 1 to 14 years of age. Approximately 20,000 children and adolescents die each year, with the majority of deaths in children less than 19 years old resulting from unintentional injury.1 In addition, each year another 100,000 children have permanent disability from injury.2 In fact, traumatic injury is the leading cause of childhood hospitalization—approximately 300,000 hospitalizations per year in the United States.3 The economic costs are staggering. Traumatic injuries are a major cause of medical spending for children ages 5 to 14 years with billions of dollars spent on caring for the pediatric trauma victim each year.3 But the impact of pediatric trauma extends far beyond statistics and is often seen in the tragedy that the family and society must endure. Therefore nurses must be able to recognize the patterns of pediatric injury and the appropriate treatment.

PATTERNS OF INJURY

The most common injuries seen in children are blunt as opposed to penetrating injuries. At least 80% of life-threatening injuries in children occur from blunt trauma.2 Blunt injuries are associated with rapid deceleration, which can occur in automobile incidents or with direct blows resulting from child abuse or contact sports activities. Blunt trauma is commonly associated with multiple injuries, which can make management of a child injured by a nonpenetrating mechanism complicated. Penetrating injuries represent approximately 20% of pediatric trauma.2

In pedestrian trauma, injuries to the left side of the patient are predominant, perhaps because vehicles are driven on the right side of the road in the United States. Skeletal injuries usually involve long bones, especially of the lower limbs.4 Chest injuries generally occur as a result of blunt trauma. Because of differences in the child’s compliant chest wall, rib fractures and flail chest are less common than in adults, but pulmonary contusions are more frequent.5 Injuries to the liver and spleen are the most common blunt abdominal injuries seen in children; other injury sites include the bowel and pancreas. Because the kidneys in children are less protected and more mobile than in an adult, genitourinary system injuries often involve the kidneys and, less frequently, the bladder and urethra.6

TRAUMA AND CHILD ABUSE

Child abuse and neglect are broadly defined as the maltreatment of children and adolescents by their parents, guardians, or other caretakers. Reports of child maltreatment in the United States continue to rise.7 The nurse has two main responsibilities in such cases: detecting and reporting. The laws on child abuse reporting are clear. In all states it is mandatory for nurses to report suspected cases of child abuse and neglect to the local protective service agency. The law protects health professionals from liability suits if suspicion proves to be wrong. Reluctance to report such information can lead to a recurrence of abuse and injury. The opportunity to help these children lies in the ability of the emergency department staff not only to appropriately treat the child but also to recognize the recurring nature of the underlying problem.

An important facet of the evaluation of pediatric trauma should be a careful examination of the child for other signs that might suggest the possibility of intentional or inflicted injury. Inconsistencies between the trauma history and the injuries sustained should alert the nurse to potential child abuse.8 Diagnostic signs of child abuse may include orbital ecchymosis in the absence of a clear causative factor. This is a serious concern because of the high incidence of subdural hematoma formation associated with vigorous shaking or jarring of an infant’s head. Skull fractures, particularly if out of magnitude with the history, should always alert the nurse to the possibility of inflicted injury. The general appearance and nutritional state of the child also may suggest neglect or maltreatment. Other diagnostic signs may include cigarette burns; unusual bruising, especially over the back or soft tissue areas of the body; and any situation in which the circumstances are not clearly defined as causative of the injury. Old fracture sites revealed on radiographic examination also should raise suspicion. Careful examination of the genitalia and anal areas always need to be part of the evaluation of the injured child. Any injury in these areas should raise suspicion of sexual abuse.

PREVENTION STRATEGIES

With the recognition that unintentional injury and death are major public health problems, nurses play a major role in injury prevention. On the basis of clinical experiences and the identification of patterns and trends related to pediatric trauma, nurses’ contributions are paramount in all multidisciplinary efforts to determine sound trauma prevention strategies.9

Most children who are killed or injured in automobile crashes are passengers. These casualties occur when an automobile collides with another vehicle or a fixed object. The use of restraints decreases fatalities from motor vehicle crush injuries by 13% to 46%.10 By communicating these facts, health professionals involved in the care of pediatric patients have been instrumental in promoting the passage of safety restraint laws in all states. Because nurses are frequently in teaching roles, they are instrumental in bringing the legislation to the user level by instructing parents in how to protect their children and how to use restraint devices correctly.

Drowning, the fourth leading cause of death in children, is most common in children under 4 years of age and in adolescent males 15 to 19 years of age.9 Prevention strategies to decrease the incidence of drowning include teaching parents never to leave an infant or young child alone during a bath, providing supervised swimming instruction for children, and installing safety fences around pools. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) helps to decrease the number of deaths if initiated early and executed effectively; therefore, CPR education is paramount.

Falls by children are not uncommon, but, although many are minor, they account for a large number of injuries and deaths each year.11 Deaths are often caused by falls from second-story windows by wandering toddlers. Nurses need to educate parents about the importance of constant adult supervision in and around the home, the installation of safety gates at the tops and bottoms of stairwells, and diligent use of window locks.

RESUSCITATION PHASE

ASSESSMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Pediatric Trauma History

A thorough history is obtained during the early evaluation of a child who has sustained multiple injuries and is included as part of the nursing database. The purpose of the history is to determine and record the nature, location, and time of injury. The history of the injury is crucial to the child’s treatment and begins at the scene of the incident. The history includes events leading to the incident, mechanism and time of injury, clinical course after the injury, contamination of wound sites, previous history of chronic illness or injury, allergies, medications, and time of the last meal eaten before injury. The Emergency Nurses Association recommends taking a CIAMPEDS history12:

The chief complaint is the reason for the child’s visit to the emergency department, which in this case is the traumatic incident. Immunizations include an evaluation of the child’s current immunization status. An allergy history is obtained in children, as with all patients. The parents are asked if the child is allergic to any medicines, adhesive tape, latex, or environmental substances. The nurse establishes whether the parents have given the child any medications recently and whether the child takes medication routinely for diabetes, seizures, lung disease, cardiac disorders, or other disease entities. Determination is made as to whether the child is under medical care for reasons other than routine well-child health care. Events surrounding the injury include mechanism, suspected injuries, prehospital assessment and treatment, and what led to the injury. Determination of when the child’s last meal was eaten is important if the child needs to be intubated, sedated, or requires surgery. Any symptoms and their progression since the time of injury are ascertained.12

Growth and Development

Physical Development.

The initial encounter with the child includes an assessment of the child’s growth and physical development, which helps to identify existing alterations that determine the approach used during the examination. This assessment is done quickly because of the critical nature of the child’s injury. An accurate estimate of the child’s size and weight (Table 29-1) is made as soon as possible so that therapy can be initiated. When time allows, however, an exact weight should be obtained because medical treatment that involves drug and fluid therapy, calculated on a perkilogram basis, must be accurately determined.

TABLE 29-1 Approximate Weights for Children

| Age | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|

| Newborn | 3 |

| 6 months | 6 |

| 1 year | 10 |

| 3 years | 15 |

| 5 years | 20 |

| 8 years | 25 |

| 10 years | 30 |

| 16 years | 50 |

Psychosocial Factors.

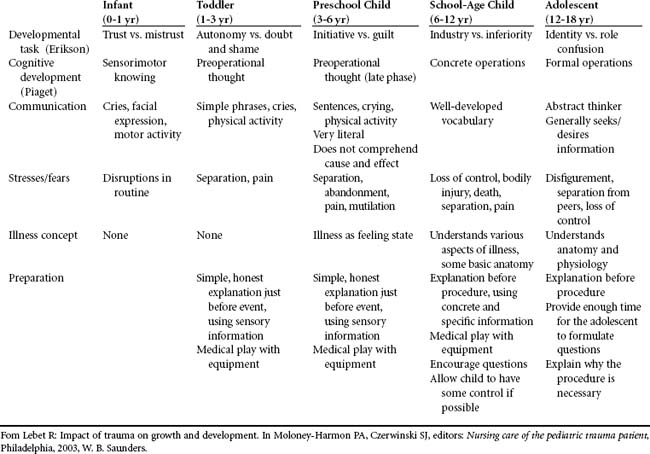

The multisystem injuries and hospitalization of a critically ill child are devastating for the child and the family. Nurses have the responsibility to do everything possible to minimize the psychologic trauma that accompanies this traumatic incident. Because stressful medical situations can become the focus of fears and the source of new symptoms for the child, pediatric emergency care must include not only physical management but also consideration of the child’s psychologic reactions to the illness. By relying on basic age-appropriate developmental characteristics, nurses can be astute to the general psychologic responses expected of the child. Table 29-2 summarizes the essential issues in this assessment process on the basis of the child’s age. Appropriate preparation for procedures is also outlined.

General Principles.

• Let the child know that someone will call the parents, and tell the child when they arrive.

• If the child brought a toy, let the child hold it.

• When speaking to the patient, get down to the child’s eye level so that the child can see your face. Speak clearly and slowly so that the child can hear you.

• Never assume that the child has understood you. Find out by questioning the child.

• Do not let the child witness treatment given to a seriously ill adult. Take the time to segregate the child to avoid additional emotional trauma.

• Be honest about the possibility of pain during the physical examination. If the child asks about being sick or hurt, tell the truth, but give reassurance by telling the child that you are there to help. If you appear calm and in control, it is more reassuring to the child.

• Touch the child and hold the child’s hand. Acceptance of you by the child shows in the reaction to your touch. Talking with the child and smiling can provide comfort.

• Always explain to the child what you are going to do.

• Do not try to explain the entire procedure at once. Explain one step, do the procedure, and then explain the next step.

• Children of all ages should be respected with regard to their feelings of bashfulness and modesty. In particular, school-age children and adolescents are modest about exposing their bodies to strangers. Keep all children covered with a hospital gown, only allowing exposure of different body parts during the physical examination.

Physical Examination

Vital Signs.

Pulses are obtained at the radial, brachial, carotid, or femoral arteries and are counted for a full minute because there are often irregularities in an anxious or injured child. A child under normal circumstances has a faster heart rate and respiratory rate and a lower blood pressure than an adult. Tachycardia is usually found in children with such conditions as fever and shock and during the initial response to stress. Bradycardia can result from increased intracranial pressure, spinal cord injury, hypoxia, hypothermia, and hypoglycemia. Table 29-3 provides normal heart rates for children.

TABLE 29-3 Normal Heart Rates in Children

| Age | Beats/Minute |

|---|---|

| Infants | 120-160 |

| Toddlers | 90-140 |

| Preschoolers | 80-110 |

| School-age children | 75-100 |

| Adolescents | 60-90 |

The respiratory rate is also counted for a full minute. Tachypnea is an initial response to stress in children. If a stressed child does not hyperventilate, head injury, spinal cord injury, or other reasons such as a distended abdomen are considered and investigated. Table 29-4 provides normal respiratory rates for children.

TABLE 29-4 Normal Respiratory Rates in Children

| Age | Breaths/Minute |

|---|---|

| Infants | 30-60 |

| Toddlers | 24-40 |

| Preschoolers | 22-34 |

| School-age children | 18-30 |

| Adolescents | 12-16 |

Blood pressures should be obtained by using a cuff size that is no less than half and no more than two thirds the length of the upper arm. If pediatric cuffs are not available, an adult cuff can be used on the child’s thigh. In the field a palpable systolic blood pressure is adequate; precious time should not be wasted to obtain a diastolic reading. The normal systolic blood pressure for individuals from 1 to 20 years of age is 90 plus two times the age in years. The diastolic pressure should be approximately two thirds the normal systolic pressure. Table 29-5 provides the normal blood pressure ranges in children.

TABLE 29-5 Normal Pediatric Blood Pressure Ranges

| Age | Systolic (mm Hg) | Diastolic (mm Hg) |

|---|---|---|

| Infants | 74-100 | 50-70 |

| Toddlers | 80-112 | 50-80 |

| Preschoolers | 82-110 | 50-78 |

| School-age children | 84-120 | 54-80 |

| Adolescents | 94-140 | 62-88 |

Respiratory Reserve.

An infant whose lung capacity is decreased compensates by increasing the respiratory rate and using auxiliary respiratory muscles, as evidenced by retractions. Retractions are an early sign of respiratory difficulty and compromise the infant’s tidal volume. Most of the child’s normal respiratory activity is affected by abdominal movement until age 6 or 7 years, and there is very little intercostal motion. A child who has a paralytic ileus after blunt abdominal trauma may have respiratory distress because abdominal distention elevates the diaphragm and interferes with pulmonary function. As a result, children in respiratory distress who are spontaneously breathing should be treated in the semi-Fowler position when spinal injury has been ruled out.

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance.

The daily fluid requirement of a child is larger per kilogram of body weight than that of an adult because the child has greater insensible water losses per unit of body weight. This is because the child has a larger surface area and a higher metabolic rate than the adult. Even with these factors, the absolute amount of fluid required by a child is small. Nurses must carefully monitor the fluid volume administered to the child to avoid overhydration. The calculation of maintenance fluid requirements is shown in Table 29-6. If the child’s fluid intake is adequate, the urine volume should average 0.5 to 1 ml/kg per hour. The nurse keeps accurate records of all possible sources of fluid loss, including laboratory blood samples, blood loss from any source, gastric drainage, vomitus, and diarrhea.

TABLE 29-6 Calculation of Maintenance Fluids (per 24 Hours) in Children

| Weight (kg) | Kilograms per Body Weight Formula |

|---|---|

| 0–10 | 100-120 ml/kg |

| 11–20 | 1,000 ml for the first 10 kg and 50 ml/kg for each kg over 10 kg |

| 21–30 | 1,500 ml for the first 20 kg and 25 ml/kg for each kg over 20 kg |

Some forms of electrolyte imbalance are more likely to occur in children than in adults. Serum glucose, calcium, and potassium levels are monitored closely in the child. Infants have high glucose needs because of high metabolic rates and low glycogen stores; therefore, the infant can become hypoglycemic quickly during periods of stress. A 25% dextrose in water bolus (0.5 to 1.0 gm/kg) helps correct this. Changes in serum potassium concentration can occur with changes in acid-base status and diuretic administration. The critically ill child does not seem to be as sensitive to hypokalemia as the adult, so cardiac arrhythmias from hypokalemia are not often seen in pediatric patients until the serum potassium is less than 3 mEq/L.13 Ventricular fibrillation is rarely seen in pediatric patients but may result from severe hypokalemia or hyperkalemia.

The administration of citrate phosphate dextran blood produces precipitation of serum ionized calcium.14 An infant who requires frequent transfusions is at risk for development of hypocalcemia, a condition that can interrupt normal cardiovascular function. The ionized calcium levels are monitored closely so that calcium supplements can be administered as needed.

Assessment in Head Trauma

Each year approximately 22,000 acutely brain-injured children in the United States die and another 29,000 are left with a permanent disability.15 In children the brain tissues are thinner, softer, and more flexible; the head size is greater in proportion to the body surface area; and a relatively larger proportion of the total blood volume is in the child’s head. Thus the child’s response to head injury differs significantly from that of an adult. Intracranial hypertension and cerebral hypoxia occur commonly in children, rendering them highly susceptible to secondary brain injury. Preventing secondary injury contributes to a significantly better outcome in the pediatric patient.16 Expandable fontanelles and open cranial sutures allow increased room for swelling, providing an advantage for the head-injured infant. The primary disadvantage in the evaluation of the head-injured child is the developmentally imposed limitation in verbal expression, which can complicate assessment endeavors.

Neurologic Assessment.

Evaluation of the level of consciousness after a head injury is probably the single most important aspect of the neurologic assessment but often the most difficult to perform in an infant or young child. Because level of consciousness means different things to different people, a uniform system such as AVPU or the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) should be used. The AVPU method is described below:

V Patient responds to vocal stimuli (This unfortunately is of little value in a very young child.)

P Patient responds to painful stimuli

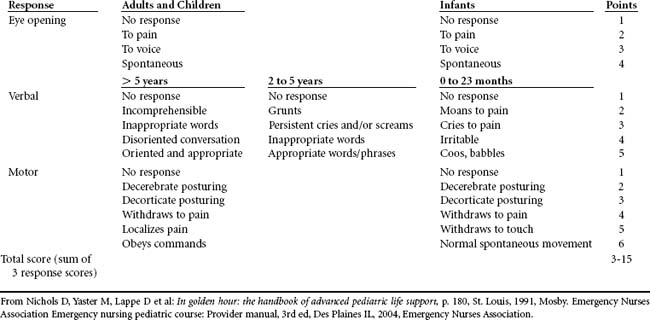

The GCS is used worldwide as a neurologic assessment tool. The scale consists of three sections, each of which measures a separate function of the person’s level of consciousness: the patient’s eye opening response, verbal response, and motor response. The total score ranges from 3 to 15, with the higher scores indicating more intact neurologic function. However, because it is difficult to use this tool to evaluate verbal response in infants and preverbal children, many clinicians use a modified GCS (Table 29-7).17

Vital Signs.

Elevated blood pressure can also indicate a rise in intracranial pressure, although hypertension in a child with multiple injuries should never be assumed to be the direct result of a head injury. Hypertension may be precipitated by anxiety or pain or may be present as a result of preexisting illness. Generally, increased intracranial pressure is accompanied by an increase in systolic arterial blood pressure, producing a widening of the pulse pressure. This compensatory mechanism occurs as the body attempts to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion pressure by initiating a rise in blood pressure.

The child with a brain injury may have several types of abnormal respiratory patterns. When intracranial pressure rises and signs of Cushing’s phenomenon are evident, the child typically has apnea. Development of a Cheyne-Stokes pattern of breathing (alternating hyperpnea and bradypnea) after the presence of a normal respiratory pattern should alert the nurse to suspect neurologic deterioration. Hyperventilation usually indicates injury to the brainstem at the level of the midbrain or upper pons.18

Head and Neck Examination

All pediatric trauma patients must be suspected of having a cervical spine injury, especially those who have sustained facial or head trauma or who complain of pain in the neck or back. Anteroposterior, lateral, and open-mouth radiographic views of the cervical spine are necessary diagnostic studies.19 Although spinal cord injury occurs infrequently in children, any time the cervical spine radiographs appear abnormal or are normal but the child is symptomatic, it is imperative that a neurosurgical consultation is obtained. Children may have a spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality (SCIWORA), which mandates continual assessment for neurologic symptoms if the child’s mechanism of injury is associated with a potential spinal cord injury.

Further neurodiagnostic evaluation is indicated in children with head injuries to identify the type and extent of injury. In patients with a head injury less than 72 hours old, computed tomographic (CT) scanning remains the imaging modality of choice for several reasons, including the limited potential for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to diagnose acute subarachnoid hemorrhage or acute parenchymal hemorrhage; the ease of monitoring unstable patients during the CT scan procedure; and the short time frame required to complete the study.15 MRI is a technique used for imaging intracranial structures and it is superior to CT scan in visualizing the posterior fossa, spinal cord structure, small vascular lesions, and most brain tumors. Lengthy procedure time, difficulty in monitoring critically ill patients during the procedure, cost, and the inability to visualize bone directly are among the limitations of this diagnostic procedure.

Assessment of Thoracic Trauma

Cardiopulmonary Examination.

The nurse palpates the neck, clavicles, sternum, and thorax. Any signs of tenderness, swelling, or crepitus are noted. Subcutaneous emphysema is a finding of significant concern. Subcutaneous air can be palpated near penetrating chest wounds. When found in the neck area, it suggests a proximal tear or avulsion of the tracheobronchial tree or an esophageal perforation. During examination of the thorax, any instability is noted. Unilateral tenderness in the upper abdomen may indicate a chest injury such as a fractured rib.

Assessment of Abdominal Trauma

Physical Examination.

The abdomen and lower chest are examined for contusions, abrasions, and lacerations that may indicate compression injury. It should be noted whether the abdomen is scaphoid or distended. If a conscious child is pulling up the lower extremities, it may be in an attempt to relieve tension on the abdominal wall, thereby reducing pain.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree