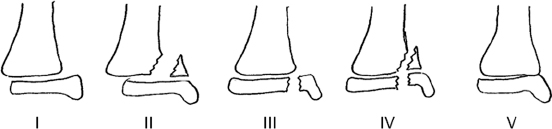

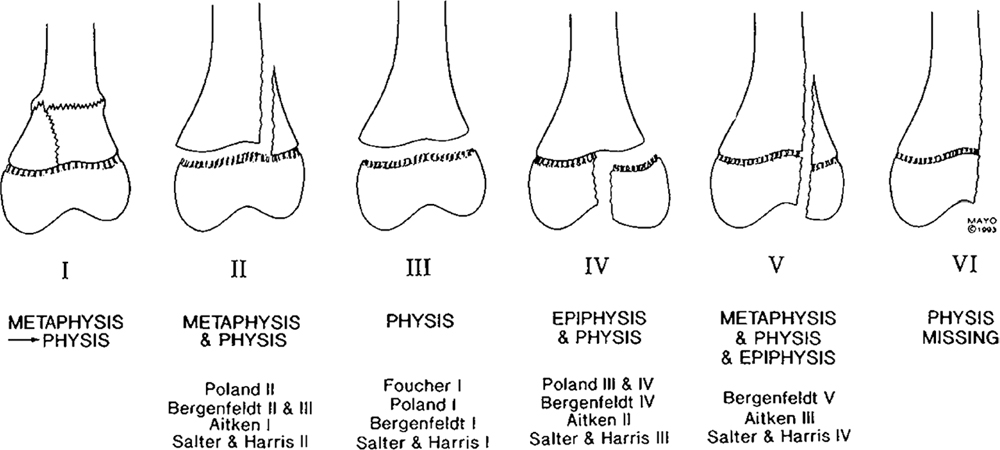

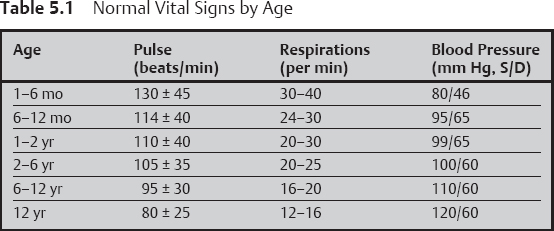

5 Pediatric Trauma This chapter provides basic principles and algorithms for trauma management in children. Common diaphyseal fractures are not covered if there are no unique pediatric features. References are provided at the end of each section for further information. 1. Classification a. There are several classification systems, including those of Aitken, Salter and Harris, and Peterson. Their goals are to (1) facilitate communication, (2) predict the risk of growth disturbance, and (3) determine treatment. b. The classifications provide information on 1) Physeal alignment 2) Articular alignment 3) Stability and risk of displacement c. Physeal damage can occur from 1) Step off at the level of the physis, with bar formation 2) Damage to and death of physeal cells 3) Ischemia of the physis if severe soft tissue damage occurs d. The classifications are usually predictive of the risk of growth disturbance. Salter 1 and 2 are typically at low risk of growth disturbance because the growth plate is not traversed by the fracture. However, there are some notable exceptions because damage may occur to the physis which is not visible on plain films. This is most common in the distal femur and the distal tibia, where there is a high risk of growth disturbance even in the “benign” fracture types such as Salter I and II. This may be due to complex physeal anatomy as well as compressive forces involved. By contrast, there is a low risk of growth plate damage in Salter 1 and 2 fractures of the distal radius and ulna and the proximal humerus. e. Salter–Harris classification: The most widely used (Fig. 5.1). Note that type V fractures are rarely, if ever, seen. f. Peterson classification: Recognizes a broader spectrum of injuries (Fig. 5.2) Fig. 5.1 Salter–Harris classification of physeal injuries. 1. Definition: A patient with more than one organ system injured or more than one component within one organ system. a. Laboratory studies: Complete blood cell count, type and cross, urinalysis, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, amylase, electrolytes b. Indications for radiographic studies 1) Cervical, thoracic, lumbar spine a) Tender b) Unconscious or heavily sedated c) Neurologically abnormal 2) Pelvis a) Tender b) Unconscious c) Hematuria present 3) Skull a) Head trauma and loss of consciousness for longer than 5 minutes, hematoma b) Skull depression c) Focal neurologic signs d) Cerebrospinal fluid from nose or middle ear e) Blood in middle ear 4) Computed tomography (CT) of the head a) Glasgow Coma Scale less than 8 b) Focal neurologic signs c) CT of the abdomen d) Shock e) Severe head injury f) Abnormal abdominal examination Fig. 5.2 Peterson classification of physeal injuries. (From Peterson HA. Physeal fractures: Part 3. Classification. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14(4):443 (Fig. 8). Reprinted with permission.) a. Physical examination 1) Primary survey: To detect most urgent priorities (ABCDE) A Airway B Breathing (ventilation) C Circulation (hemorrhage) D Disability (neurologic status) E Exposure (temperature) 2) Secondary survey a) Complete physical examination b) History of event c) Medical history d) Laboratory and radiographic results e) Reevaluation and stabilization 3) Normal vital signs for children (Table 5.1) 4) Glasgow Coma Scale (Table 5.2) 3. Adjuncts in management a. Intracranial pressure measurement indications 1) Glasgow Coma Scale less than 5 or less than 8 if shock is present 2) CT scan showing mass or shift 3) Progressive neurologic deterioration b. Parenteral nutrition 1) Indicated in polytrauma patient if enteral feeding not expected within 24 hours c. Repeat physical examination

Pediatric Trauma

Pediatric Trauma

Basic Principles

Basic Principles

Physeal Fractures

Management of the Polytrauma Patient

Response | Score |

|---|---|

Eye opening |

|

None | 1 |

To pain | 2 |

To voice | 3 |

Spontaneous | 4 |

Verbal |

|

none | 1 |

incomprehensible | 2 |

inappropriate | 3 |

disoriented | 4 |

oriented | 5 |

Motor |

|

none | 1 |

decerebrate | 2 |

decorticate | 3 |

withdraws from pain | 4 |

localizes to pain | 5 |

obeys commands | 6 |

Total | Up to 15 points |

1) Should be performed at 24 and 48 hours because of the incidence of missed injuries

2) Bone scan is an alternative

d. Indications for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in polytrauma

1) Oral contraceptive use

2) Vascular injury

3) Sickle cell anemia

4) Prolonged immobility in older adolescent

Pediatric Shoulder Injuries

Pediatric Shoulder Injuries

Principles

1. The proximal humeral physis is one of the most active in the skeleton, contributing 80% of the length of humerus; therefore it has tremendous remodeling potential.

a. Begins at 6 months in proximal humeral epiphysis, and growth ceases at 15 years in girls and 18 years in boys

b. Ossific center for greater tuberosity appears at age 1; medial clavicle physis closes at around 23 years

Birth Fracture

1. Risk factors

a. Difficult delivery

b. Large size

c. Breech presentation

2. Presentation

a. “Pseudoparalysis” –limb moves little

b. Rule out sepsis, brachial plexus injury

3. Diagnosis

a. Plain radiographs or ultrasound

4. Treatment: Ace wrap or arm to chest for 2 weeks

Proximal Humeral Fractures

1. Background

a. Age-based patterns: Preadolescent usually has fracture of metaphyseal region; adolescent, physeal fracture; Salter II or I

b. Mechanism: Axial load or abduction; external rotation

c. Muscle insertions with respect to physis: Internal and external rotators all on proximal fragment; deltoid and pectoralis, distal fragment displaces anteriorly and medially

2. Criteria for acceptable alignment

a. Child under age 12 years: Virtually any alignment is acceptable.

b. Child over age 12 year: Shortening or overlap less than 3 cm

c. Angulation less than 45 degrees

3. Classification of displacement (pediatric)

a. Neer and Horowitz

• I: Less than 5 mm translation

• II: 5 mm to 33%

• III: 33 to 66%

• IV: Greater than 66% (most are grade IV)

• Translation itself is not a problem. Note: Appearance on emergency department film is not the same as the appearance later. Angulation usually improves.

4. Treatment methods

a. Sling

b. Traction

c. Shoulder spica

d. Abduction brace

e. Internal fixation

5. General recommendations

a. Sling and swathe as long as any growth remains

b. Closed or open reduction and internal reduction and internal fixation if

1) Unacceptable angulation or shortening; older than 12 years

2) Severe head injury with spasticity

3) Polytrauma: To facilitate management

4) Vascular injury

5) Tenting skin: Risk of breakdown

6. Fracture through unicameral bone cyst (UBC)

a. Common cause of proximal humerus fracture in child

b. Differential diagnosis

1) Eosinophilic granuloma

2) ABC (aneurysmal bone cyst)

3) Fibrous dysplasia

4) Fibrous cortical defect

c. Treatment of UBC

1) Sling to heal fracture: 4 to 6 weeks

2) Cyst regresses about 20% of time

3) Assess and discuss the risk of refracture with family

a) Depends mainly on cortical thickness

4) Inject or bone graft if:

a) Persistently thin cortex

b) High desired activity level

c) Family prefers active treatment

5) May need several injections

Sternoclavicular Injuries

1. Medial clavicle is last epiphysis to appear and to close (≤ 23 years old).

2. It provides 80% of clavicle growth.

3. Injury may be a dislocation or a fracture.

4. CT is most accurate if diagnosis is unclear.

5. Signs of significant displacement:

a. Venous congestion

b. Decreased pulse

c. Difficulty breathing, swallowing

d. Sensation of choking

6. Treatment

a. Anterior displacement: usually no treatment

b. Posterior displacement: treat if significant symptoms

c. Closed reduction; may use towel clips

d. Internal fixation: use sutures if unstable

Bibliography

Bae DS, Kocher MS, Waters PM, Micheli LM, Griffey M, Dichtel L. Chronic recurrent anterior sternoclavicular joint instability: results of surgical management. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(1):71–74

Baxter MP, Willey JJ. Fractures of the proximal humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:570–573

Price CT, Flynn JM. Management of fractures. In Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL eds. Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1429–1489

Pediatric Elbow Injuries

Pediatric Elbow Injuries

Lateral Condyle Fracture

1. Background

a. Vascular supply to the capitellum and lateral trochlea enters posteriorly

b. Fracture may occur with varus or valgus force

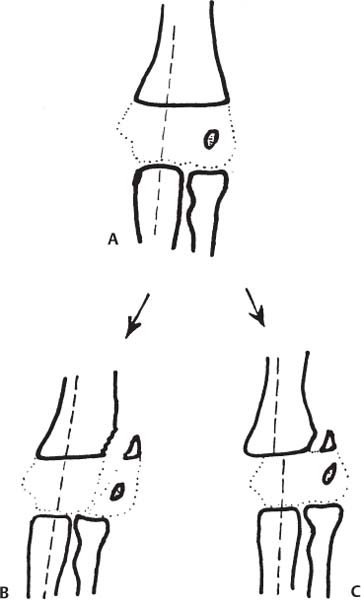

c. Distinguish this injury from a transphyseal separation by lack of swelling and tenderness medially and by alignment of the humerus with the forearm (Fig. 5.3); ultrasound may help.

d. Internal oblique radiograph shows the fracture best.

Fig. 5.3 Differentiation of lateral condyle from distal humeral physeal fracture. In the latter, displacement of the entire forearm follows the metaphyseal fragment. In minimally displaced fractures, physical examination, ultrasound, arthrogram, or magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful. (A) Normal alignment of ulna and humerus. (B) Alignment maintained in lateral condyle fracture. (C) Alignment is lost in distal humeral Salter II physeal fractures.

2. Principles and significance

a. Lateral condyle fracture is one of the few pediatric fractures in which nonunion is not rare.

b. Cast is rarely able to maintain reduction of a displaced lateral condyle.

3. Treatment recommendations

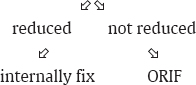

a. Displacement less than 2 mm→ splint in 90 to 100 degrees of flexion; pronation: recheck at 5 and 10 days (open reduction, internal fixation [ORIF] if further displacement)

b. Displacement greater than 2 mm or follow-up is unreliable: attempt closed reduction (optional)

1) Avoid posterior dissection; visualize reduction anteriorly

2) Internal fixation: Two divergent pins preferred

3) May cross physis if needed

4) May use screw; remove later

5) Usually remove pins and splint at 6 to 8 weeks

c. Fiberglass allows best visualization of fracture

d. Late presentation (displaced and ununited longer than 6 weeks)

1) Approach anteriorly with graft and rigid fixation if in good position (early). Operate only for lateral instability symptoms if after 3 weeks. Avoid excessive dissection.

2) Valgus osteotomy if significant deformity exists

3) Ulnar nerve anterior transposition if deformity is increasing

Medial Epicondyle Fractures

1. Background

a. Medial epicondyle begins to ossify at 4 to 6 years; fuses at around 15 years of age

b. Fracture most common in ages 9 to 12 years

c. Significance of this fracture

1) Medial collateral ligament of ulna attaches to the base of the epicondyle.

2) Entrapped medial epicondyle may be missed.

3) Look for medial condylar extension.

2. Treatment

a. Principle: Displacement is well tolerated unless forceful loading is anticipated.

b. Indications for ORIF

1) Epicondyle in joint despite attempt at manipulation

2) High valgus stresses anticipated (dominant arm of throwing athlete, etc.) in patient with displaced epicondyle. “Stress test” in 15 degrees of flexion may be of interest, but most are unstable acutely; no specific guidelines for interpretation of this test exist.

1) Exposure is easier in prone position. May use screw or percutaneous pin. Ulnar nerve transposition is not recommended in most cases.

d. Indications for closed reduction: All cases not meeting the preceding criteria for ORIF, including the following special cases:

1) Acute ulnar neuropathy: Likely to resolve with time; not a specific indication for ORIF or ulnar nerve transposition

2) Displacement greater than 5 mm but not intra-articular

3) Epicondyle fracture with elbow dislocation

4) Technique of closed reduction: Extend elbow, wrist, and fingers simultaneously with slight valgus

Elbow Dislocations

1. Background

a. More common in older children

b.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree