Pediatric Athlete

Joseph Bernard

INTRODUCTION

Youth participation in organized sports has grown dramatically over the past couple of decades. The health care provider caring for the younger athletes should be aware of the differences in their anatomy and physiology as compared to adults.

The pediatric athlete is often still growing and many injuries are related to the changes that have or have not occurred yet during this phase of development. The specialization of sport at younger ages also places greater repetitive stress on a young athlete’s body.

In evaluation of the skeletally immature pediatric athlete with bony injuries, consideration needs to be made regarding physeal (growth plate) injuries. The Salter-Harris classification, which is a radiographic classification, has been designed to further describe these fractures. Acute injuries to the growth plate are seen in an estimated 15% to 20% of injuries to the long bones and are often seen with sports participation. These are about two times more common in the upper extremity and are seen more often in boys than in girls.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY

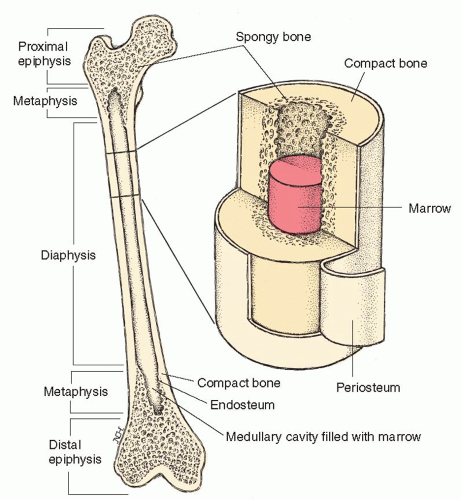

The differences between adult and pediatric anatomy are crucial to the understanding of the unique types of injuries pediatric athletes sustain. Despite children’s bones being weaker than those of adults, they are more plastic and absorb more energy before breaking. This means that incomplete fractures are common, that is, buckle-greenstick fractures. The periosteum is also much thicker than that in adults and is more readily elevated from the metaphysis and diaphysis of the bone and can reduce the incidence of complete periosteal rupture. The residual intact periosteum has useful functions in stabilizing the fracture and promoting healing (Fig. 24.1).1

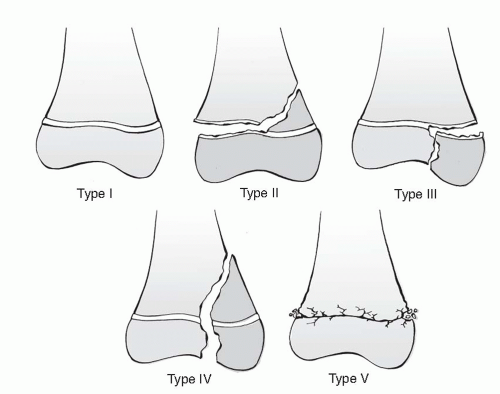

The physis “growth plate” is an organized system of tissue located at the end of long bones and is primarily responsible for horizontal growth. This area of the long bones is important in the pediatric population because injury can cause growth deficiency and limb length discrepancy. The physis is the transition zone between the metaphysis and the epiphysis. The physis is the “weakest link” in this structure. It is much more common to have an injury to the physis than to the tendons or ligaments. Salter-Harris type I fractures occur through the cartilage in the physeal zone. Salter-Harris type II fractures extend through the physis and the metaphysis. These are the most commonly seen fractures in this population. A Salter-Harris type III fracture extends through the physis to the epiphysis. Salter-Harris type IV injuries cross through the epiphysis, physis, and metaphysis. Salter-Harris type V fractures are classified as a compression-type injury to the physis and are usually not apparent on initial radiographs and can lead to growth arrest (Fig. 24.2).

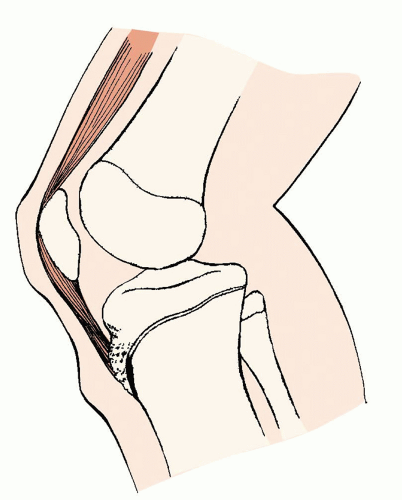

Apophyses are small cartilage growth centers found at the attachment of tendons and ligaments to bones in the young athlete. The apophyses close at various rates, and common sites include the tibial tubercle (Osgood-Schlatter disease), calcaneus (Sever disease), and medial epicondyle (little league elbow). Apophyses have decreased tensile strength and are susceptible to repetitive overuse traction injury, apophysitis, as well as potential apophyseal avulsion injury (Fig. 24.3). The chronic traction injury results in microavulsions at the bone-cartilage junction. This is common during periods of rapid growth. The fusion of each apophysis occurs at differing times in development, and it is important for the sports medicine physician to be aware of this when evaluating the young athlete.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Overuse musculoskeletal injuries should be considered in atraumatic pain in a pediatric athlete. Apophyseal injuries need to be considered in this population because of the inherent weakness of the open apophysis. Common apophyseal injuries include Osgood-Schlatter disease (patellar tendon at tibial tubercle), Sever disease (gastrocnemius-soleus complex at the calcaneus), Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome (patellar tendon at the lower pole of the patella), hip flexor apophysitis (sartorius at the anterior superior iliac spine [ASIS] and rectus femoris at the anterior inferior iliac spine [AIIS]), and little league elbow (medial epicondyle of elbow). A total of 724 cases of tendinitis or apophysitis were diagnosed in 445 patients seen in the Sports Medicine Division at Boston Children’s Hospital between 1980 and 1990. Of the 193 male and 253 female patients aged 8 to 19 years, boys and girls aged 16 years represented the largest groups. There were 88 injuries to the upper extremity and 636 to the lower extremity.2

FIG. 24.1. Anatomy of pediatric long bones. Reprinted with permission from Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. 27th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. |

FIG. 24.3. Apophysitis with avulsion injury, Osgood-Schlatter disease. LifeART image copyright © 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved. |

Other common overuse injuries in the pediatric athlete include tendinosis, stress fractures, articular cartilage degeneration, and joint pain related to muscle weakness or imbalances (such as patellofemoral syndrome and multidirectional shoulder instability).

Acute injuries such as occult fractures and avulsion fractures need to be excluded. Growth plate fractures are common in the pediatric population due to incomplete closure of the physis. Mann and Rajmaira collected data on 2,650 long bone fractures, 30% of which involved the physes.3 Neer and Horowitz evaluated 2,500 fractures to the physes (growth plate) and determined that the distal radius was the most frequently injured (44%), followed by the distal humerus (13%), and distal fibula, distal tibia, distal ulna, proximal humerus, distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal fibula.4

NARROWING THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES

History

A thorough history will guide the evaluator and help narrow the differential diagnosis. The age of the athlete is very important, as pediatric athletes present with different acute and overuse injuries than the mature athlete. The mechanism of injury will help differentiate between an overuse injury and an acute injury. This should include the sport that the athlete participates in, the position he or she plays, the level that he or she competes at, and how often he or she plays or takes time off for recovery. Asking what factors exacerbate the symptoms and what has helped to alleviate them is also important. Associated symptoms such as pain, swelling, or feeling of instability are useful.

When there is a traumatic injury in a pediatric athlete, it is important to obtain a history of when the injury occurred, the mechanism of the injury, the ability to continue to participate in the sport where the injury occurred, the area and intensity of the pain, and a history of prior fractures in that location. The age of the athlete and knowledge of when the various growth plates close are useful if a Salter-Harris fracture is suspected. Associated symptoms such as swelling, numbness, or weakness should be reviewed.

When an apophyseal injury is suspected, the immature athlete will complain of pain at or near the apophyseal site with activity. The pain will usually get better with rest. An injury or trauma preceding the development of pain would make an apophysitis less likely. The athlete may also report a recent growth spurt.

When a pediatric athlete presents with knee pain, it is important to know the age of the athlete, the history of when the pain started (acute or chronic), the location of the pain, the mechanism of injury, the sports that the athlete participates in, the level of sports participation and the amount of time for recovery between participation, the factors that make the pain better or worse, any prior history of knee pain, and what treatments have been tried. If there is not a particular event that brought on the pain, an overuse injury should be suspected. With anterior knee pain, pain associated with the patellofemoral extensor mechanism should be considered. Swelling after an acute injury may signify an internal ligamentous or meniscal derangement. Locking or catching is often seen with a meniscal tear, but the athlete may also describe some locking sensations with patellar tracking abnormalities associated with patellofemoral syndrome. If the location of the pain is near the tibial tubercle, an apophysitis may be suspected.

Evidence-based Physical Examination

When a young athlete presents with traumatic or atraumatic musculoskeletal pain, the area of pain should first be inspected for any deformities, skin changes, or swelling. The bones and joints should be palpated, assessing for deformities or tenderness. In the pediatric athlete, specific knowledge of the areas that still exhibit an open physis or apophysis should be considered. Many mild pediatric physeal and apophyseal injuries will have normal radiographs so diagnosis is based on mechanism and location of tenderness on examination.

Evaluation for range of motion of any joints in the area of pain and strength testing may help evaluate for associated muscle or tendon injuries. Strength testing can be manual or dynamic, such as single leg squat.

Ligamentous laxity would be concerning for an unstable joint due to a ligament sprain. Pediatric athletes often have hypermobile joints that may be normal. Comparison of unaffected side when dealing with an extremity can often elucidate if increased laxity is normal or pathologic.

Special tests will vary depending on the area of the body in question, but may be necessary to further rule out any specific injury. One such test is the Stork test or single-leg hyperextension test for suspected spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

For the pediatric knee examination, inspection of the knee is useful to evaluate for an effusion, for patellar alignment and mobility, and for ecchymosis associated with a traumatic injury. Palpation of the bony anatomy should be done to evaluate for possible fractures. If there is tenderness over the tibial tubercle or the lower patellar pole, Osgood-Schlatter disease or Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease should be considered. Peripatellar tenderness may signify some patellofemoral pathology. Joint line tenderness would be seen if there is a meniscal tear. Special tests can also be used. A positive McMurray test is seen with meniscal pathology, a positive Lachman test is seen with a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament, and laxity or pain with varus or valgus stress would be seen with sprains of the lateral or medical collateral ligaments, respectively. A patellar compression may be seen with patellofemoral syndrome. A positive Ober test is seen with iliotibial friction syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree