Chapter 131 Patellar Revision

Reasons for compromised patellar bone at the time of revision are numerous, with iatrogenic causes being common. Over-resection or asymmetrical resection of the patella can compromise the residual bone stock and limit reconstructive options. Excessive medial malpositioning of the patellar component with osseous impingement and lateral subluxation of the remaining patella on the femoral component can lead to bony erosion or can cause implant loosening and migration.4,29 Bone fragmentation and compromise of fixation can be caused by disruption of the vascular supply to the patella from extensive lateral dissection or retinacular release.4 Loose patellar components can lead to bony erosion. Berend and associates reported a 4.2% loosening rate in 4287 all-polyethylene patellar components, with a mean time to loosening of 2.6 years, although only a minority went on to revision.4

Osteolysis is another cause of patellar bone loss. Wear debris is most commonly generated from the tibiofemoral articulation but can also come from the patellofemoral articulation. Increased wear of the patellar polyethylene implant is seen in cases of high contact loading with low conformity of patellar and trochlear geometries.17 Maltracking of the patella may create high-contact loading forces and may lead to wear.10 Polyethylene patellar components sterilized with gamma irradiation in air have been associated with failure due to wear,26 as have metal-backed patellar implants.3

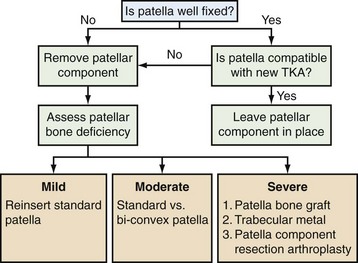

Whether the patellar revision is done for an isolated problem or as part of a revision in which other components are being revised, a number of treatment options are available. An algorithm for direct management is presented in Figure 131-1 and will be discussed later in this chapter.

Figure 131-1 Algorithm to guide management of the patella at the time of revision knee arthroplasty. See text for details.

The Well-Fixed Patella

The patellar component is often well fixed at the time of revision knee arthroplasty, and retention of this component is an attractive option when certain criteria are met. This approach is simple and avoids the potential morbidity of removal of a well-fixed implant and catastrophic compromise of the extensor mechanism.22 Patellar component retention is feasible in many cases of aseptic revision total knee arthroplasty. In contrast, the patellar component should always be removed at the time of one-stage or two-stage revision done for deep prosthetic infection.

A well-fixed patellar component must be compatible with the prosthetic design of the rest of the knee to consider retention. The surgeon is often faced with the dilemma of leaving a patellar component that is mismatched with the implants used for revision of the femur and tibia. Patellar tracking can be used to gauge the appropriateness of leaving the patellar implant. Proper tracking ensures that the patellar component geometry is reasonably compatible with the femoral trochlear design, that it has been implanted in an appropriate position, and that the overall patellar height is acceptable. Care must be taken to ensure that lateral subluxation of the patellar component has not resulted from an internally rotated femoral component, likely the greatest iatrogenic cause of maltracking in the revision setting.22 A patellar component that is technically poor, from the asymmetrical resection of bone or from overstuffing of the patellofemoral articulation, is an indication for removal.

Concerns about subtle mismatches in geometry and conformity between patellar and femoral components from different manufacturers have not been shown to lead to deleterious clinical results.26 Looking at 73 total knee revisions, Barrack and associates2 reported that retaining a well-fixed patellar component gives equivalent short-term clinical results and patient satisfaction compared with those obtained by successfully reimplanting a new patellar component. Lonner and colleagues26 reported similar good results with retention of a well-positioned, stable, all-polyethylene patellar component in 202 revisions, provided that the polyethylene was not oxidized.

Catastrophic wear or substantial surface damage to the patellar implant is a clear indication for revision. However, minimal wear may be acceptable. Quantifying the exact amount of acceptable wear or deformation for component retention is impossible; the surgeon may consider patient age and activity level in that decision. Given that forces generated at the prosthetic patellofemoral joint are often greater than the yield strength of polyethylene,30 there is likely to be some wear or deformation of most patellar implants, and mild damage should not be an indication to revise all components.22 Late failure due to wear from retained patellar components has been reported when the polyethylene was sterilized with gamma irradiation in air; revision should be considered in the presence of obvious oxidation.26

Many authors have stated that the presence of a metal-backed patellar implant is an indication for revision because of the poor track record and high rate of failure of many of these designs.3,13,25,37 A review of metal-backed patellar components suggested that most large series reported a failure rate of approximately 6% to 8%, with late failures seen commonly at 6 or 8 years secondary to polyethylene wear and exposure of the metal backing.37 However, others have argued that a well-fixed, undamaged, metal-backed component can be left in place with a reasonable expectation of success.2 Some mobile-bearing metal-backed patellae have a good track record and may allow for isolated patella–polyethylene exchange in selected cases. Certain metal-backed patellae are extremely difficult to remove, and doing so risks removal of significant bone and fracture. The surgeon must assess the potential risk of future failure due to a retained metal-backed component against the morbidity associated with patellar revision. It seems reasonable to retain a metal-backed patellar component when other criteria for component retention are met, particularly when the remaining bone stock is poor.16

Patellar Component Removal

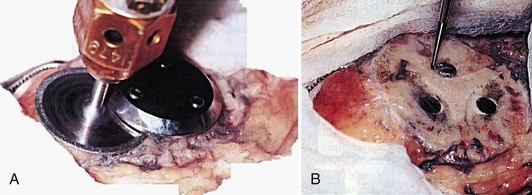

A well-fixed metal-backed implant can be difficult to remove, and removal performed haphazardly risks bone loss or fracture. A diamond wheel cutting tool is often useful in separating the baseplate from the underlying host bone (Fig. 131-2).11 If the metal-backed design includes lugs, they are typically well ingrown and can be removed with a fine-tipped high-speed burr after removal of the baseplate. Alternatively, it is reasonable to consider leaving well-fixed lugs and covering them with the new patellar implant during aseptic revision. This can be accomplished by varying lug design (e.g., by using a central peg design when revising a three-pegged component) or by slightly repositioning the lugs when the host patellar bone allows.

Patellar Component Revision

Usually, it is technically feasible and reasonable to implant a revision patellar component when only mild or moderate bone loss is encountered. Although the exact thickness of bone required for an onlay all-polyethylene patellar component has not been precisely defined, a uniform thickness of 10 to 12 mm has been described as adequate.35 A traditional onlay component may be used by preparing a flat surface and drilling new lug holes in the remnant bone. Meticulous removal of fibrous tissue and good cementation technique are important. Prior defects from lug holes and areas of cavitary bone loss can be filled with cement. An implant that matches the design of the femoral component should be used.

When a patellar implant fails, isolated patellar revision has been associated with disappointing results and a relatively high rate of recurrent failure.5,24 This is likely due to an incomplete understanding of the mechanism of patellar failure, which is often multifactorial and includes component rotation, relative “overstuffing” of the anterior compartment, lateral placement of the patellar component, and residual tightness of the lateral retinacular structures.24

Berry and Rand reported on 42 knees that underwent isolated revision of the patellar implant.5 A relatively high complication rate was seen, including five late patellar fractures and a 19% reoperation rate directly related to the extensor mechanism. Adequate vascularity and thickness of the residual bone stock were felt to be important factors in a durable outcome. Other studies have reported worse outcomes following isolated patellar procedures compared with those who had undergone concomitant femoral revision.34

An inset biconvex patella may be used when an intact rim of bone remains but central cavitary bone loss is too great to provide support for a traditional onlay button (Fig. 131-3). Restoration of the composite thickness of the patella may be achieved with a thick but small-diameter button.16 The biconvex design allows for successful implantation in the patella with as little as 5 mm of central bone, although residual thickness less than 6 mm has been associated with fracture and implant failure.12,18 Published clinical results of this technique have generally been good with few complications reported at midterm follow-up.18,27 In a recent report of 89 revision biconvex patellar implants, 2 cases of aseptic loosening and fracture were seen in association with avascular necrosis, to give a 98% survival rate at 10 years and 86% at 14 years.12 Absence of a supportive rim of bone was thought to be a risk factor for radiographic loosening. The authors concluded that the presence of vascular bone was an important determinant in the satisfactory outcome of revision with a biconvex component.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree