Osteochondritis Dissecans

Cecilia Pascual-Garrido

Mark A. Slabaugh

Nicole A. Friel

Brian J. Cole

INTRODUCTION

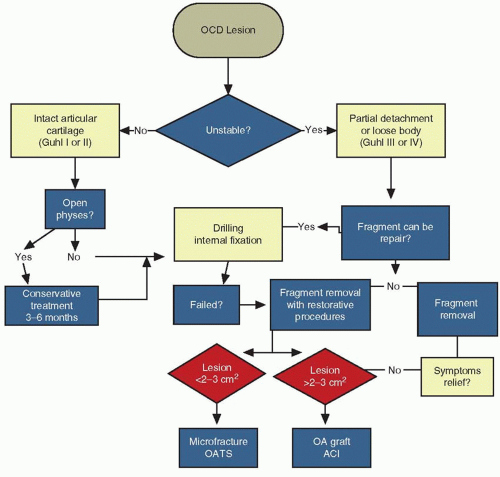

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a pathological condition that results in destruction of subchondral bone with secondary damage to overlying articular cartilage (6,13). OCD is classically divided into juvenile and adult forms on the basis of the patient skeletal maturity (6). Juvenile OCD occurs in children and young adolescents who have open growth plates. Although adult OCD may arise de novo, it is more commonly the result of an incompletely healed previously asymptomatic juvenile OCD lesion (21). Juvenile OCD has a much better prognosis than does adult OCD, with higher rates of spontaneous healing with conservative treatment (5). Adult OCD lesions have a greater propensity for instability and once symptomatic, typically follow a clinical course that is progressive and unremitting (31). The highest incidence rates in juvenile OCD appear among patients between 10 and 15 years old, ranking among the most common causes of knee pain and dysfunction in young adults (5,31,36). The prevalence of OCD is estimated at 15 to 21 per 100,000 (28). Lesions most frequently occur on the femoral condyles but are also found in the elbow, wrist, ankle, and femoral head (3,7,18,44,48). Nonoperative treatment (activity modification) drilling and fragment fixation are strategies to preserve the native articular cartilage. Restorative biological therapies such as marrow stimulation, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft, and fresh osteochondral allograft (OA) are indicated to replace the damaged cartilage with hyaline or hyaline like tissue when preservation fails (40) (Fig. 43.1).

PRESENTATION AND IMAGING

The typical presentation of OCD in the knee includes pain and swelling related to activity. Instability is not usually reported, though mechanical symptoms (catching or locking) do usually occur in the presence of a loose body and are frequently the initial presenting symptoms. On physical exam, patients typically have tenderness localized over the OCD lesion. More than 70% of OCD lesions are found in the “classic” area of the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle (MFC) intersecting the intercondylar notch near the PCL. Central lateral condylar lesions account for 15% to 20% and femoral trochlear lesions for <1%. Patellar involvement is uncommon (5%-10%) and is typically located in the inferior medial area (31).

The patient may walk with an antalgic gait or with the leg externally rotated (Wilson sign) to decrease pressure over the lesion (39). Effusion, decreased range of motion, and quadriceps atrophy are variably present depending upon the severity and duration of the lesion (17).

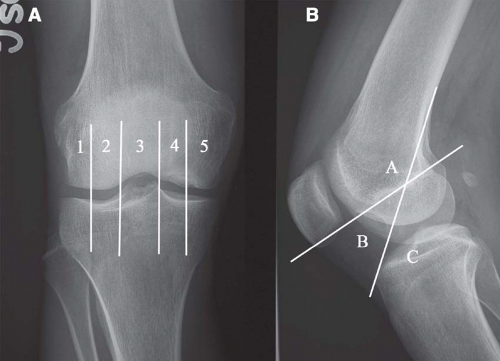

Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knee permit localization of the lesion and assessment of the physeal status of the patient. Additional images such as tunnel or sunrise views are useful for suspected distal MFC or patellar lesions, respectively. By convention, lesions may be anatomically localized using the Cahill classification (6) (Fig. 43.2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the mainstay in diagnosis of OCD lesions. Lesion qualities including bone edema, subchondral separation, and cartilage condition may be evaluated prior to determining a treatment course (Fig. 43.3). Intraoperatively, OCD lesions may be classified using the criteria suggested by Guhl (25) (Table 43.1).

TABLE 43.1 Description of the Guhl’s Classification | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

NATURAL HISTORY AND PROGNOSIS

The natural history of untreated OCD lesions is poorly defined. Most adult OCD cases arise from established untreated or unrecognized juvenile OCD. Many younger adult OCD patients have a history of knee symptoms dating back to a time when their physes were open. These cases probably represent juvenile OCD that did not heal and evolved to adult OCD. Spontaneous healing of juvenile OCD lesions has been reported when the lesion is not in the classical location of the lateral aspect of the MFC (11).

Neither the literature nor our experience allows us to definitively determine whether untreated OCD, either with the fragment in situ or following fragment excision, categorically has a more significant likelihood of developing symptomatic DJD in the future. Linden performed a long-term retrospective follow-up study of patients with OCD of the femoral condyles with an average follow-up of 33 years after initial diagnosis (36). It was concluded that individuals who are older when the osteochondritis manifests (adult OCD) have an increasing incidence of gonarthrosis with age. In contrast, OCD diagnosed in childhood have no increase risk of osteoarthritis later in life when compared to the normal population. In contrast, Twyman et al. (53) completed

a prospective follow-up of 22 knees with juvenile OCD into middle age and found 50% had some radiographic signs of osteoarthritis. The likelihood of osteoarthritis development was also found to be proportional to the size of the area involved.

a prospective follow-up of 22 knees with juvenile OCD into middle age and found 50% had some radiographic signs of osteoarthritis. The likelihood of osteoarthritis development was also found to be proportional to the size of the area involved.

Early studies evaluating the results of treatment of these lesions focused on fragment excision. Denoncourt et al. (12) treated 37 patients with arthroscopic removal of the fragment and curettage of the lesion. They reported complete “healing” in ten cases by second-look arthroscopy. They recommended this treatment in adults and children who have failed initial attempts at nonoperative treatment. Similarly, Ewing and Voto (16) excised the fragments and drilled the defect in 29 patients. They reported a satisfactory result in 72% of their patients with short-term (<1 year) follow-up. Recent reports suggest that fragment excision may provide short-term pain relief but not provide long-term success with further follow-up. Anderson et al. (1) evaluated 19 patients with 20 OCD lesions who were treated with fragment excision. Follow-up between 2 and 20 years showed that only five patients could participate in strenuous activity without significant symptoms. Eleven patients had pain with activities of daily living, and the remaining three patients had pain with light activities. It was concluded that fragment excision may show improvement of the symptoms in the short term, but the remaining defect and involved compartment may worsen with time.

Contemporary surgical decision making is based upon patient age, skeletal maturity, lesion appearance, and clinical symptoms. Stable OCD lesions in young patients have a favorable prognosis when treated initially with nonoperative treatment. The ideal goal of conservative treatment is to obtain lesion healing before physeal closure. Authors who focus on the biology of the fragment-subchondral bone interface argue that the knee should be protected in a knee immobilizer and treated similar to an intra-articular fracture (6). Alternatively, some authors place a premium on the health of the articular cartilage and note the value of continuous motion (6). Hughston et al. (28) demonstrated the detrimental effects of prolonged immobilization, including stiffness, atrophy, osteopenia, and, potentially, chondropenia. Traditional nonoperative treatment for juvenile OCD consists of an initial phase of knee immobilization with partial weight bearing (4-6 weeks) in those patients in whom no detachment is noted on MRI. Once the patient is pain free, weight bearing as tolerated is permitted and a rehabilitation program emphasizing knee range of motion and low-impact strengthening exercises ensues. If there are radiographic and clinical signs of healing at 3 or 4 months after the initial diagnosis, patients

may participate in a gradual return to sports with increasing intensity allowed in the absence of knee symptoms. The likelihood that the lesion will heal with this management is approximately 50% at 10 to 18 months (7).

may participate in a gradual return to sports with increasing intensity allowed in the absence of knee symptoms. The likelihood that the lesion will heal with this management is approximately 50% at 10 to 18 months (7).

Operative treatment is indicated for young patients with detached or unstable lesions or those approaching physeal closure whose lesions have been unresponsive to nonoperative management (6,16). Operative treatment may also be considered in patients who are unable participate in or intolerant of a prolonged nonoperative course. In contrast, adult OCD typically follows a clinical course requiring early surgical intervention (21). A large multicenter review of the European Pediatric Orthopedic Society study (509 knees, 318 juvenile, and 191 adult in 452 patients) suggests an improved prognosis with conservative treatment in young patients with a small lesion (<2 cm2) in the classic location with no signs of dissection or effusion. In cases of chondral separation, surgical results are better than those with nonsurgical treatments (27,50).

SURGICAL OPTIONS

Reparative Treatments

The goal of reparative procedures is to restore the integrity of the native subchondral interface and preserve the overlying articular cartilage (39). Interventions such as drilling or internal fixation are indicated for the symptomatic juvenile patient who has failed a course (generally 3-6 months) of nonoperative treatment. Depending on the severity of symptoms, when the presence of significant mechanical symptoms dominates the clinical presentation, a decision to operate might occur earlier, especially when the MRI shows a detached articular fragment. These procedures provide clinical relief in a majority of patients and leave many viable options for revision in case of inadequate symptomatic relief.