Chapter 21 Orthoses for overuse disorders of the upper limb

Lateral epicondylitis

Anatomy and symptoms

Lateral epicondylitis, or tennis elbow, is a very common condition of the lateral elbow. Patients generally present to the clinic with pain and localized tenderness of the extensor origin and lateral epicondyle of the humerus. Onset may be acute or insidious. Generally, the patient complains of increased pain with wrist extension or with gripping. In severe cases, the patient may complain of pain with lifting very light objects. Activities requiring full elbow extension and forearm pronation aggravate the discomfort. The pain of lateral epicondylitis often is accentuated by extreme wrist flexion from passive stretch of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) muscle or by active contraction of the wrist extensors. The pain may not be isolated to the lateral epicondyle but actually may radiate proximally or distally.9,11,26,27 Lateral epicondylitis is believed to be a tendinosis of the origin of the ECRB. Although the specific etiology is unknown,2 it is postulated that microtears at the origin of the common extensor muscle mass, involving the extensor digitorum communis, extensor carpi radialis longus, supinator, and ECRB, are the likely precipitating factor for this condition. Many investigators believe that these small tears are caused by overuse and repetitive injury and strain of the common extensor origin at the lateral epicondyle. The instigating injury is the result of forced flexion of the wrist and fingers during extensor muscle contraction. Such mechanisms are seen with racquet sports where backhand volleys are required. As these microtears try to heal, continued use of the upper extremity causes continued strain and reinjury to the muscle origins.10,26,27 This can lead to degeneration and possible avascularity at the muscle origin, which in turn leads to chronic inflammation causing the injured areas to remain weak and painful.

Splinting lateral epicondylitis

The primary goal of splinting lateral epicondylitis is to decrease the pain and inflammation at the origin of the ECRB. Several splints have been described in the literature.2 One of the most common splints used is the wrist cock-up splint (Fig. 21-1). This rigid orthosis maintains the wrist in extension to offload the extensors of the forearm and promote healing at the muscle origin.10 The appropriate posture of the wrist in the splint has been described in various positions, ranging from 0 to 45 degrees of extension.4,10 Janson et al.10 compared three types of wrist orthosis—dorsal wrist splint, volar wrist splint, and semicircumferential wrist design—varying the amount of wrist extension and then evaluating muscle limitations by surface electromyography (EMG). The semicircumferential splint showed the greatest change in EMG electrical activity of the extensor muscles: a 6% decrease. The authors concluded that this reduction of electrical activity was comparable to the reduction of electrical activity of the wrist extensors seen while a proximal forearm counterforce brace was worn. Based on these findings, combined with the limited functional use while a rigid wrist orthosis was worn, the authors did not recommend wrist splinting. Clinically, we have found that compliance with a rigid wrist splint is poor because of the device’s functional limitations.

Fig. 21-1 Wrist cock-up splint with wrist positioned in extension to relieve tension on the wrist extensors.

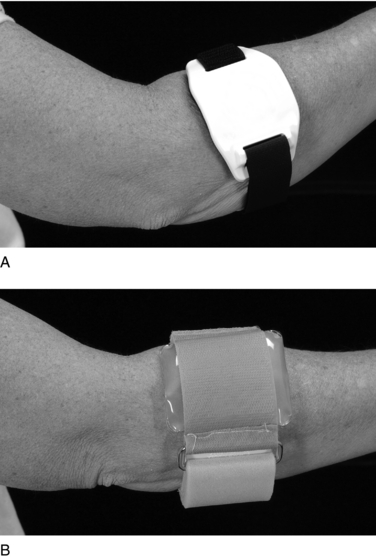

The forearm support band or counterforce brace (Fig. 21-2) is a common splint prescribed for lateral epicondylitis. The counterforce brace decreases the force of the muscle contraction by inhibiting muscle expansion and reducing tension at the musculotendinous unit proximal to the band.17 The counterforce brace essentially changes the functional origin of the extensor mass to a site distal to the radial head. This may assist in resting the origin of the common extensor tendon to permit healing.9,17

Fig. 21-2 A, Band-ItTM (Pro Band Sports Industries) forearm band has medial and lateral supports, making it effective for both lateral and medial epicondylitis. B, Aircast® pneumatic armband (Northcoast Medical; Smith & Nephew Rolyan). Meyer et al.17 showed the greatest reduction in EMG activity of the wrist extensors with this counterforce brace.

Several designs of forearm bands are on the market. Both standard and Aircast® counterforce braces showed reduced EMG activity of the extensor muscles, with the greatest reduction of EMG activity seen with the Aircast® band (Fig. 21-3).17 Further studies are needed to determine recommended wearing time and amount of pressure with application, but it is generally agreed that the counterforce brace should be worn for painful activities during the day and removed for any periods of inactivity. The brace typically is applied approximately 2 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle. It should be fit with a comfortable amount of pressure while the muscles are relaxed so that maximum contraction of the wrist extensors is prohibited. Potential complications with use of the counterforce brace include compression of the radial nerve or the anterior interosseous nerve, edema, and venous congestion. Clinically, we have found more positive compliance with the counterforce brace because it leaves the hand completely free for functional use.

In acute cases of painful lateral epicondylitis, an initial trial of complete immobilization may be necessary. An example is a long arm splint with the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion, the forearm neutral, and the wrist positioned in comfortable extension.27 The other splinting methods previously described can be initiated once the acute pain has been relieved to a functional level.

Cubital tunnel syndrome

Anatomy and symptoms

Ulnar nerve compression at the medial elbow is known as cubital tunnel syndrome. The cubital tunnel is a fibroosseous tunnel at the elbow situated between the humerus and ulnar heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. The cubital tunnel is bordered laterally by the ulnohumeral collateral ligament and anteriorly by the medial epicondyle. The roof of the cubital tunnel, known as Osborne’s, is a fibrous band confluent with the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris starting just proximal to the medial epicondyle.22

Prolonged elbow flexion or repetitive elbow flexion and extension can be a major causative factor to cubital tunnel symptoms. Apfelberg and Larson1 described the condylar groove, where the ulnar nerve passes, as rounded and spacious during extension and flattened and triangular with elbow flexion, causing increased pressure on the ulnar nerve. Rayan et al.21 showed that elbow flexion produces a significant rise in pressure at the condylar groove, and pressure increases further at the cubital tunnel when elbow flexion is combined with shoulder elevation.22,24 Many patients experience an increase in symptoms at night because their elbows are flexed during sleep. Other potential causes of cubital tunnel syndrome include elbow injury and inflammation, and direct trauma or pressure to the ulnar nerve. Ulnar nerve subluxation or traction also may cause symptoms.

Splinting cubital tunnel syndrome

Patients with mild symptoms and no motor changes generally respond well to conservative splinting. The primary goal of splinting for this condition is to decrease pain and paresthesias. Immobilization with the elbow in extension decreases the stretch on the ulnar nerve and prevents repetitive motion that can promote an inflammatory response within the cubital tunnel. An elbow pad can be used during the day to protect the ulnar nerve from trauma or direct pressure.24

Night splinting is essential to prevent sleeping with the elbow flexed beyond 90 degrees. Splints for wear at night can be a custom-fit device or an off-the-shelf type pillow splint. Full elbow extension allows for the least amount of pressure on the ulnar nerve; however, most patients will not be able to tolerate immobilization in full extension. Therefore, a custom splint should be fit with the elbow in comfortable extension, anywhere between 30 and 60 degrees of flexion.3 The splint is generally fit anteriorly to avoid direct pressure on the nerve at the posterior medial elbow (Fig. 21-3). In our clinic, we have found this type of splint to be effective, yet the rigidity of the splint makes compliance questionable. For the elbow we tend to use a soft splint known as the Posey Soft SplintTM (Fig. 21-4) The Posey soft splint is a filled with polystyrene beads. The splint is easily applied with hook-and-loop closures and prevents elbow flexion. This splint is bulkier than the custom splint, but it is not rigid, is lighter and more comfortable, and improves patient compliance.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Anatomy and symptoms

Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common compression neuropathy of the upper extremity. The carpal tunnel is a small narrow space in the volar wrist that houses the median nerve, flexor pollicis longus, four flexor digitorum profundus tendons, and four flexor digitorum superficialis tendons as they course through the forearm into the hand. The tunnel is formed by the concave arch of the carpal bones and the transverse carpal ligament, which extends from the scaphoid tuberosity and trapezium radially, and attaches to the pisiform and the hook of the hamate on the ulnar side of the hand. The carpal tunnel has a defined space with little room for expansion. An increase in the volume of the contents of the tunnel will have a detrimental compressive effect on the tendons and median nerve, resulting in symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. Numerous causes of median neuropathy include inflammatory synovitis, trauma, repetitive flexion/extension, and autoimmune and endocrine disorders (Table 21-1).

Table 21-1 Factors involved in the pathogenesis of carpal tunnel syndrome