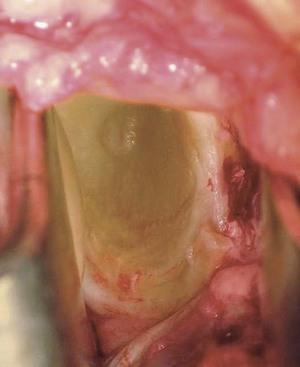

Chapter 12 The shoulder capsule is large, loose, and redundant to allow the large range of shoulder motion. There are three main ligaments in the anterior capsule that help prevent subluxation or dislocation: the superior glenohumeral ligament, the middle glenohumeral ligament, and the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex (IGHLC). Damage to the IGHLC, which supports the inferior part of the shoulder capsule and acts like a hammock, is related to most cases of anterior instability. The Bankart lesion,1 involving detachment of the IGHLC insertion on the glenoid, is the most common pathologic lesion associated with traumatic anterior instability (Fig. 12-1). Defects or injuries to the superior and middle glenohumeral ligaments may also contribute to instability.2 The diagnosis of an anterior dislocation is usually readily apparent.3 The patient typically gives a history of a specific injury in which the shoulder “popped out.” In some cases, dislocation occurs with no history of significant trauma; these patients are frequently noted to have generalized ligamentous laxity and are less likely to demonstrate a Bankart lesion. The diagnosis of anterior subluxation is often more subtle. The chief complaint may be a sense of movement, pain, or clicking with certain activities. Pain, rather than instability, may be the predominant complaint. In throwers and other overhead athletes, “dead arm” episodes may occur during which the patient experiences a sharp pain followed by loss of control of the extremity.4 It should also be noted that patients who report multiple dislocations, atraumatic dislocations (in sleep), or continued instability should be evaluated for potential bone loss on the anterior glenoid. Contraindications to the open technique include voluntary instability and concomitant psychological issues. Large defects of the humeral head (Hill-Sachs lesions) or glenoid may require supplemental bone grafting to fill the defects5; however, the recent trend toward increased performance of the Latarjet procedure may be an overreaction. The literature has shown consistently high levels of success with conventional open techniques of stabilization (without bone blocks) in patients with bony defects of the humeral head and/or glenoid. Owing to success with the procedure described later, in my practice the Latarjet procedure is considered only in patients who have glenoid defects involving more that 30% of the glenoid diameter or in patients with humeral head defects involving more than 25% of the head and with a depth of at least 1 centimeter. I seldom perform bone block procedures except in revision cases. I prefer to use arthroscopic methods of stabilization in throwing athletes. If an open method is used in this group, I recommend the technique of anterior capsulolabral reconstruction described by Jobe,6 in which the subscapularis tendon is split rather than detached. The basic procedure for the open surgical treatment of recurrent anterior instability is a modification of the Bankart procedure1 and involves repair of the anterior capsule and labrum to the glenoid.11 In most cases the capsular ligaments are stretched as well as detached, and the procedure is also designed to remove any abnormal laxity.

Open Repair of Anterior Shoulder Instability

Preoperative Considerations

Indications and Contraindications

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine