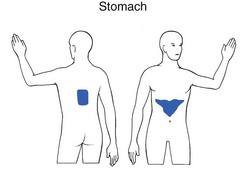

All visceral structures belonging to the thorax or abdomen may give rise to pain felt in this area (see Ch. 25). In that the discussion of these disorders is principally the province of internal medicine, only major elements in the history that are helpful in differential diagnosis from musculoskeletal disorders are mentioned here. Acute chest pain is summarized in Box 1. It is traditionally accepted that pain felt in the chest radiating into the left arm is indicative of myocardial ischaemia, especially when the patient reports it as pressure, constriction, squeezing or tightness. However, none of these descriptions, which are usually regarded as characteristic of ischaemia, is of definitive aid in the differential diagnosis from other non-cardiogenic problems in the thorax. Even relief of pain after the intake of glyceryl trinitrate does not offer absolute confirmation of coronary ischaemia. For clinical diagnosis, a combination of several elements must be present, of which the most important is pain spreading to both arms and shoulders initiated by walking, especially after heavy meals or on cold days.1 Pain that arises from the pericardium is the consequence of irritation of the parietal surface, mainly from infectious pericarditis, seldom from a myocardial infarction or in association with uraemia. When pericarditis is the outcome of one of the latter two causes it is usually only slight. Pain is normally located at the tip of the left shoulder, in the anterior chest or in the epigastrium and the corresponding region of the back. Three different types of pain can be present. First and most obvious, but rarely encountered, is pain synchronous with the heartbeat. Second is a steady, crushing substernal ache, indistinguishable from ischaemic heart disease. Third and most common is pain caused by an associated localized pleurisy, which is sharp, usually radiates to the interscapular area, is aggravated by coughing, breathing, swallowing and recumbency, and is alleviated by leaning forward.2 Although the clinical presentation of pneumonia may vary, classically the patient is severely ill with high fever, pleuritic pain and a dry cough.4 Malignant mesothelioma is a diffuse tumour arising in the pleura, peritoneum, or other serosal surface. The most frequent site of origin is the pleura (>90%), followed by peritoneum (6–10%), and only rarely other locations. Mesothelioma is closely associated with asbestos exposure and has a long latency (range 18–70). There is no efficient treatment and the overall survival from malignant mesothelioma is poor (8.8 months).5,6 This is characterized by a sharp superficial and well-localized pain in the chest, made worse by deep inspiration, coughing and sneezing. Viral infection is one of the most common causes of pleuritic pain.7 Viruses that have been linked as causative agents include influenza, parainfluenza, coxsackieviruses, respiratory syncytial virus, mumps, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus.8 Pulmonary embolism is the most common potentially life-threatening cause, found in 5–20% of patients who present to the emergency department with pleuritic pain.9,10 Predisposing factors for pulmonary embolism are: phlebothrombosis in the legs, prior embolism or clot, cancer, immobilization, prolonged sitting (aeroplane), oestrogen use or recent surgery.11 This warrants special attention because 90% of patients suffering from this disorder complain of musculoskeletal pain.12,13 It is frequently mistaken for a shoulder lesion or even for thoracic outlet syndrome, an error which leads to a delay in diagnosis and treatment.14 Orthopaedic clinical examination produces an unusual pattern of clinical findings. There is often a complicated mixture of cervical, shoulder and thoracic signs. Passive and resisted movements of the cervical spine may be limited and/or painful, the result of involvement of the scaleni and sternocleidomastoid muscles. On examination of the shoulder girdle, a restriction of both active and passive elevation of the scapula may be present. More positive signs are detected during examination of the shoulder.15 Both active and passive elevations of the arm are limited because of spasm of the pectoralis major muscle. Passive shoulder movements may be considerably limited in a non-capsular way. Some resisted movements are weak. The neurological examination of the upper limb shows weakness and atrophy of the muscles on which consequent is extension of the tumour to the lower trunks of the brachialis plexus (Fig. 2). The only abnormal finding during thoracic examination is pain and limitation on lateral flexion towards the unaffected side explained by putting the affected thoracic wall under stretch. The clinical picture of Pancoast’s tumour may be completed by some typical findings that are caused by an ingrowth of neurological and vascular structures at the apex of the lung.16 • Horner’s syndrome: this is characterized by an ipsilateral slight ptosis of the upper lid, miosis of the pupil and enophthalmos, together with decreased sweating on the same side of the face. It is the outcome of involvement of the ascending sympathetic pathway at the stellate ganglion on the side of the tumour.17 • Hoarseness: this is the result of involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which innervates the voice cords. The hoarseness is unusual and unlike that caused by local laryngeal problems. • Oedema and discoloration of the arm: this occurs if the subclavian vein is obliterated by the tumour. All the symptoms and signs mentioned (summarized in Box 2), either singly or in combination, call for careful clinical chest examination followed by further investigation by chest radiography or other imaging methods. This is frequently due to a hernia of the stomach through the diaphragmatic hiatus. Pain is felt around the xiphoid process, can be very severe and may radiate to the rest of the sternum, into the back and between the scapulae.18 Pyrosis or heartburn, which begins if the patient lies down immediately after meals, together with a burning sensation on eructation, are the most typical symptoms.

Disorders of the thoracic cage and abdomen

Referred pain

Pain referred from visceral structures

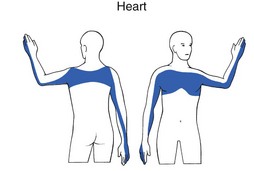

Heart (Fig. 1)

Ischaemic heart disease

Pericarditis

Aorta

Pleuritic pain

Aetiologies

Pneumonia

Pleural tumour

Pleuritis

Pulmonary embolism

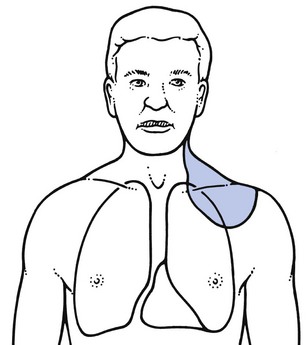

Superior sulcus tumour of the lung (Pancoast’s tumour)

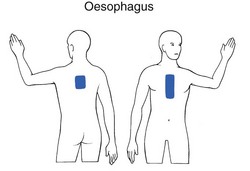

Oesophagus (Fig. 3)

Reflux oesophagitis

of the thoracic cage and abdomen

hours after meals. A bout of symptoms over weeks or months may be followed by a similar period of relief. Pain in the back suggests a posterior ulcer that has penetrated a structure such as the pancreas.

hours after meals. A bout of symptoms over weeks or months may be followed by a similar period of relief. Pain in the back suggests a posterior ulcer that has penetrated a structure such as the pancreas.