Chapter 21 Obstetrics

Woman and Child Health

The health of a nation is often reflected in the health of its mothers and newborns. The World Health Organization (WHO) often uses a nation’s maternity and neonatal morbidity and mortality statistics as a proxy for the health status of its population. It is an important summary reflecting social, political, health care delivery, and medical outcomes in a geographic area. The United States, despite its economic wealth and medical resources, consistently ranks poorly in such measures as maternal and infant mortality rates. In 2005 in the United States, 28,384 infants died before reaching their first birthdays, an infant mortality rate (IMR) of 6.9 per 1000 live births. Despite a more than 9% reduction in IMR between 1995 and 2005, the United States ranks 30th, after such select countries as Japan, the Scandinavian countries, and Canada (Box 21-1). In 2005, the U.S. IMR was more than three times as high as that in Singapore (2.1 per 1000 live births), the country with the lowest reported IMR. This number reflects in part the continuing disparities in health access and delivery for U.S. citizens (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2009).

Box 21-1 International Infant Mortality Rate (IMR)∗

From National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus.htm.

Note: U.S. data used in this table is final mortality data. After 1994, Peristats uses period-linked birth/infant death data to calculate IMRs. Rates in table may vary slightly from other rates on PeriStats: www.marchofdimes.com/peristats.

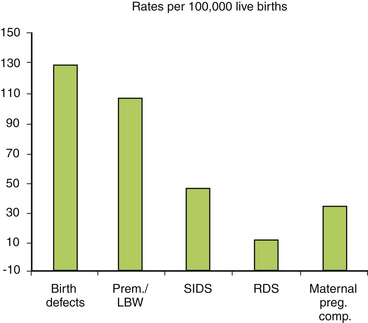

The causes of infant mortality are multiple, with birth defects being the leading cause, with a 2005 rate of 134.6 per 100,000 live births. Preterm birth (birth at <37 completed weeks of gestation) or low birth weight (LBW) is the second leading cause of infant mortality in the United States. Preterm birth rates differ by race; during 2003–2005 (average), IMR (per 1000 live births) in the United States was highest for black infants (13.3), followed by Native Americans (8.4), whites (5.7), and Asians (4.8) (NCHS, 2010). This persistent disparity contributes to the relative high IMR in the United States compared with similarly developed countries. Other causes of infant mortality include sudden infant death syndrome, respiratory distress syndrome, and maternal pregnancy complications. These five causes accounted for more than half of all infant deaths in 2005 (Fig. 21-1). Despite gains, the rate of preterm birth, birth defects, and LBW remain relatively constant. This indicates a need for further health initiatives to address the health needs of the pregnant woman and the unborn.

Preconception Counseling

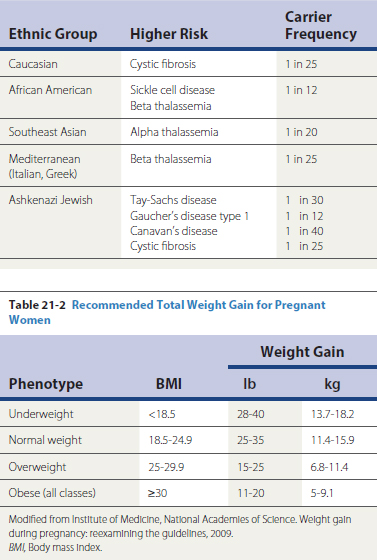

Many genetic disorders are now amenable to prenatal diagnosis through direct analysis of the underlying mutations, analysis of their protein products, or abnormal metabolites. Genetic counseling should include a systematic assessment of family history of both parents. This can be through a targeted questionnaire or formal genetic counseling by a genetic counselor or geneticist (Box 21-2). The family physician should be aware of the ethnic makeup of the practice and especially familiar with disorders in these groups (Table 21-1). When targeted screening reveals an area of potential concern, formal genetic counseling should be obtained. With advances in discovery of the genetic basis for many diseases, the list of disorders amenable to prenatal diagnosis grows daily.

Box 21-2 Genetic Screening/Teratology Counseling

Table 21-1 Genetic Screening/Teratology Counseling

| Ethnic Group | Higher Risk | Carrier Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | Cystic fibrosis | 1 in 25 |

| African American | 1 in 12 | |

| Southeast Asian | Alpha thalassemia | 1 in 20 |

| Mediterranean (Italian, Greek) | Beta thalassemia | 1 in 25 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish |

Nutrition

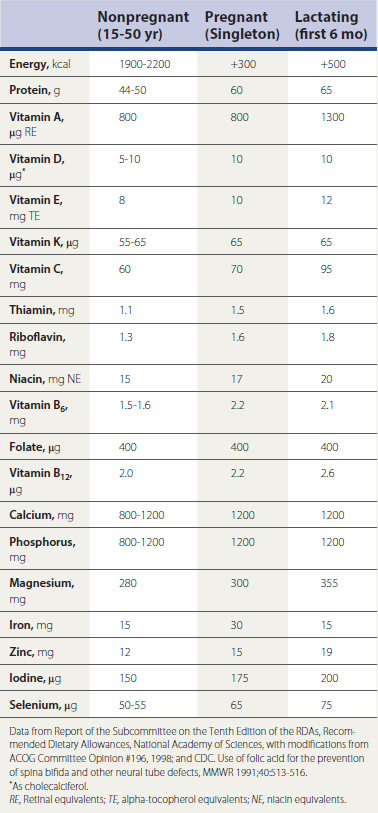

There is sufficient data to confirm that poor nutrition during the prenatal period is associated with adverse pregnancy outcome, specifically intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preterm delivery. Specific nutritional guidelines have been developed based on a woman’s prepregnancy weight or, more specifically, her body mass index (BMI) (Table 21-2). Caloric intake of an extra 300 kcal daily is sufficient for adequate maternal weight gain and fetal growth.

However, because many U.S. women do not consume adequate vitamins and minerals (Block and Adams, 1993), and specific assessment of nutritional intake is often difficult, supplements are now widely used. Recommended daily allowances for pregnant women have been established and continue to be reevaluated (Table 21-3). Care must be taken to avoid toxicity of the fat-soluble vitamins, in particular vitamin A (retinol), where “more” is not necessarily better. Daily doses of retinol greater than 10,000 IU, approximately 3000 retinol equivalents (RE), have been associated with birth defects (Rothman et al., 1995). Women who do not consume sufficient milk products may benefit from calcium supplementation. This can easily be accomplished by prescribing an antacid that is made of calcium carbonate, most easily taken in chewable form. This will not only replenish calcium stores but also treat reflux esophagitis, which often occurs in the latter half of pregnancy.

Medical Risk Assessment

Routine Prenatal Care

First Prenatal Visit

The first prenatal visit is one of the most important, particularly if the woman has not had preconception care (Box 21-3). The first prenatal visit should occur shortly after the woman discovers she might be pregnant and should be viewed as a continuation of preconception counseling. Home pregnancy test kits have a sensitivity and specificity of at least 95%; many can detect pregnancy by the fifth menstrual week. The most important aspects of the first prenatal visit include education, risk assessment, appropriate laboratory testing, and establishment of gestational age.

Box 21-3 Expert Panel Recommendations for First Prenatal Visit

From Rosen M, Merkatz I, Hill J. Caring for our future: a report by the expert panel on the content of prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:785.

Education is an important component of prenatal care, particularly for women who are pregnant for the first time. Frequency of prenatal visits should be explained, with information about the physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy. Preparation for the birthing process is a key theme around which to discuss care issues and choices such as breastfeeding. Structured educational programs to promote breastfeeding have unclear effectiveness. Pregnant women should be counseled about the risks of possible teratogens, including smoking, alcohol, and drug use, including exposure to medications, prescriptions, OTC drugs, and herbal remedies. Good handwashing is always encouraged because this is one of the best ways to avoid community-acquired infectious diseases. Appropriate immunizations such as influenza and novel influenza A (H1N1) virus should be offered. Common exposures such as workplace conditions and use of hot tubs and saunas should be explored. Exercise should also be encouraged if there is no obstetric contraindication (Box 21-4). Intercourse during pregnancy should be actively addressed because some women are reluctant to discuss this topic even with their physician. Sexual activity can generally continue during pregnancy except for few situations, such as placenta previa and preterm labor. Counseling regarding sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and their avoidance should occur. Nutrition should be individualized, with an estimate of desirable weight gain given to the pregnant woman.

Box 21-4 Recommendations for Exercise in Pregnancy

Modified from ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 189, 1994.

The physical examination during the first prenatal visit should include careful assessment of uterine size. If there is a discrepancy between menstrual age and uterine size, ultrasound should be considered early in the pregnancy to resolve the issue of dating. Recent evidence suggests that early sonography provides more accurate dating, which is important for timing screening tests and interventions and for optimal management of complications such as post-term pregnancies (Neilson, 2004). Late ultrasound, after 24 weeks, is not as sensitive for confirming gestational age. Additionally, any irregular bleeding or abdominal pain should prompt the practitioner to obtain sonographic confirmation of viability of the pregnancy as well as its normal intrauterine location.

Follow-up Prenatal Visits

According to the report of the Expert Panel on Prenatal Care (Rosen et al., 1991), low-risk primigravid women should have at least 10 prenatal visits; low-risk multiparous women should have at least eight visits. Again, however, data suggest that antenatal visits could be reduced without adverse effect to the mother and child (Carroli et al., 2001). Women with psychosocial issues or pregnancy complications should be seen more frequently. In the first two trimesters, prenatal visits may be 5 to 6 weeks apart if no problems have been ascertained. Frequency of visits should increase after 30 weeks, with weekly visits after 37 weeks. Specific recommendations are noted in Table 21-4. Routine visits for low-risk women should be scheduled at times that recommended laboratory testing could be accomplished. Prenatal screening for chromosomal abnormalities is available in the first trimester between 10 weeks, 2 days and 13 weeks, 6 days. Structural defects of the fetus (in particular neural tube defects) and karyotypic abnormalities in the form of alpha-fetoprotein based tests (Quad screen, see below) can be obtained at 16 to 18 weeks. Screening for gestational diabetes is recommended at 26 to 28 weeks of gestation, as well as screening for anemia with a hemoglobin or hematocrit. Antibody screening, Rh0(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) prophylaxis for D-negative mothers, and repeat testing for infectious diseases for at-risk mothers are recommended at this time.

Table 21-4 Expert Panel Recommendations for Visits throughout Pregnancy

| Activity | Week/Trimester |

|---|---|

| Check for any exposure to infection.∗ | |

| Physical Examination | |

| Blood pressure | 24† |

| Weight | Each visit |

| Fundal height/growth | 16† |

| Fetal lie/presentation/engagement/heart rate∗ | 24† |

| Cervical examination | 41∗ |

| Laboratory Tests | |

| Hemoglobin/hematocrit | 24-28 |

| Rh sensitivity‡ | 26-28 |

| Diabetic screen | 26-28 |

| Repeat syphilis‡ | Third trimester |

| Repeat gonococcal and HIV‡ | 36 |

| Serum alpha fetoprotein | 14-16 |

| Ultrasound∗ | When indicated |

| Health Promotion Activities | |

| Teratogen avoidance | Each visit |

| Safer sex∗ | Each visit |

| Maternal seatbelt use | Each trimester |

| Smoking cessation‡ | Each trimester |

| Work/nutrition counseling‡ | Each visit |

| Signs of preterm labor | Second/third trimester |

| Physical/emotional changes∗ | First/third trimester |

| Sexuality counseling∗ | Last half of pregnancy |

| Fetal growth/development | Each visit |

| Self-help for discomforts‡ | Each visit |

| General health habits | Each visit |

| Breastfeeding | 26† |

| Infant car seat safety | Each visit |

| Childbirth/parenting classes | 32 |

| Family roles adjustment | 38 |

| Information about laboratory tests∗ | Before testing |

| Birth plan∗ | Third trimester |

| Labor (when to call/where to go)∗ | Third trimester |

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

∗ Accepted by panel but not specifically reviewed.

† That week and each week thereafter.

From Rosen M, Merkatz I, Hill J. Caring for our future: a report by the expert panel on the content of prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:785.

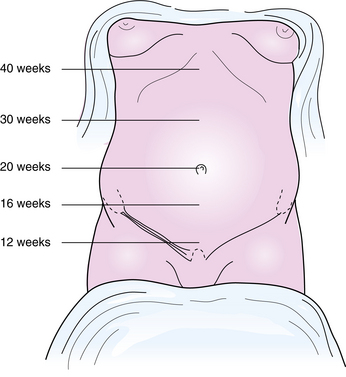

The clinical components of routine prenatal visits are controversial. Most guidelines recommend routine assessment with fundal height and maternal weight and blood pressure measurements, fetal heart auscultation, urine testing for protein and glucose, and questions about fetal movement. The assessment of uterine growth and size should be performed at every prenatal visit. Documentation of fetal heart tones is also recommended with each prenatal visit. Before 12 weeks’ gestation, the size of the uterus is estimated by bimanual pelvic examination. The ability to assess the presence of fetal heart tones using Doppler ultrasound before 12 weeks is variable. After 12 weeks and before 20 weeks, adequate uterine growth is assessed by location of the uterine fundus in the lower abdomen (Fig. 21-2). Fetal heart tones should be reliably heard during this period. At 20 weeks of gestation, most women have a palpable fundus at the umbilicus. After 20 weeks, fundal height is measured using the distance from top of the symphysis pubis to top of the fundus. The number of completed weeks of gestation should equal this measurement in centimeters (±2 cm). This measurement should be performed as accurately as possible. The most common reasons for inconsistency between menstrual age and fundal height is an inaccurate menstrual-age assignment and inaccurate measurements caused by maternal obesity. Larger-than-expected fundal height may also be caused by multiple gestation, uterine fibroids, polyhydramnios, or a large-for-gestational-age (LGA) fetus. Smaller-than-expected fundal height should warrant an exploration for etiologies such as oligohydramnios, IUGR, and fetal demise.

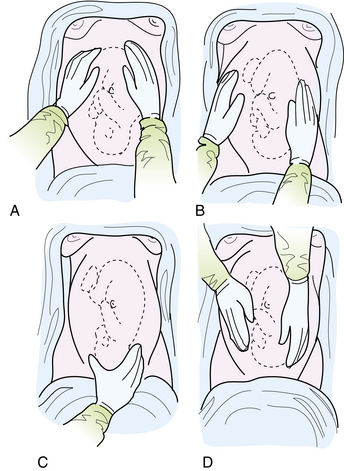

By 30 weeks’ gestation, the fetus is large enough that it can be palpated through the maternal abdomen. Position of the fetus should be documented at this and subsequent visits. This is easily done in most women by Leopold’s maneuvers (Fig. 21-3). The first maneuver involves palpation of the uterine fundus to identify the fetal part that is there. The palpating hands then glide downward laterally to perform the second maneuver, location of the fetal back. In the third maneuver the hands are cupped around the presenting part at the level of the symphysis pubis to determine the presenting part as well as its degree of descent into the pelvis. If the presenting part is cephalic, the fourth maneuver will determine its degree of flexion. The examiner now turns 180 degrees to face the mother’s legs, and the cephalic prominence is palpated. Another aid in ascertaining the position of the fetal back is the location of the fetal heart tones by Doppler sonography or auscultation. These sounds are best heard through the fetal back; in the left lower uterus in left occiput anterior, transverse, and posterior positions of the fetal head; and the right lower uterus in right occiput positions. The evidence supporting the previous practices is variable but continues as the standard of care (Kirkham et al., 2005).

Prenatal Genetic Diagnostic Testing

Amniocentesis

Maternal Biochemical Screening

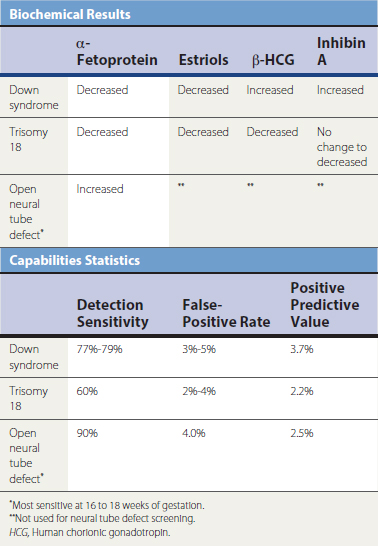

Biochemical testing is the measurement of certain chemicals in the mother’s blood found to be predictive of fetal abnormality. The quadruple screen is a maternal blood test in which one maternal sample drawn at 15 to 20 weeks (but most sensitive at 16 to 18 weeks) is assayed for alpha fetoprotein, estriols, and beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Normal ranges vary for each gestational week. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) elevations can result from open neural tube defects such as spina bifida or anencephaly, when the protein leaks from the fetal tissue into the amniotic fluid through the amniochorion and into the maternal system. A lower-than-expected MSAFP suggests Down syndrome. The addition of β subunit of hCG and estriols has improved sensitivity for the detection of chromosomal abnormalities (Table 21-5). This test should be offered to any pregnant women with appropriate counseling regarding sensitivity and specificity. Women with abnormal tests should be referred for targeted ultrasound and possibly amniocentesis.

First-trimester ultrasound and biochemical screening are now available for clinical use, specifically the “First Trimester Screen” performed between 10 weeks, 2 days and 13 weeks, 6 days of gestation. Testing involves an ultrasound measurement of the nuchal translucency (lymphatic fluid at fetal neck) (Fig. 21-4) and laboratory measurement of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) and β subunit of hCG. The First Trimester Screen has about 85% sensitivity for Down syndrome detection at 4% false-positive rate. Several tests are also available that combine a first-trimester screen with a second-trimester screen for even higher sensitivity. Physicians should become familiar with the sensitivity, specificity, and availability of the test most suitable for their practices.

Drug and Chemical Exposures in Pregnancy

This classification is an oversimplification, and the individual practitioner will need to weigh the available data in the management of the pregnant woman. Few absolutes are possible in the field of human teratology; however, current recommendations for common drug categories in pregnancy are summarized in Table 21-6. It is important to emphasize that it is difficult to demonstrate an actual cause-effect relationship between a specific drug and an adverse pregnancy outcome. At no time, however, should a drug be considered safe because no data exist.

Table 21-6 Drugs and Exposures in Pregnancy

| Agent | Recommendation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Antihistamines | Acceptable | Most are category B. |

| Decongestants | Acceptable | Pseudoephedrine preferred. |

| Cough medication with guaifenesin | Acceptable | — |

| Acetaminophen | Acceptable | Preferred analgesic and antipyretic. |

| Aspirin | Avoid | Increases risk of bleeding; no benefit in preeclampsia; may be prescribed in low doses for specific conditions. |

| NSAIDs | Avoid | Premature closure of ductus arteriosus. |

| Cephalosporins | Acceptable | — |

| Sulfonamides | Avoid in third trimester. | Kernicterus in newborn. |

| Tetracyclines | Avoid | Discoloration of teeth. |

| ACE inhibitors | Avoid | Stillborn, renal abnormalities, renal failure in newborn. |

| Immunizations | Avoid live, attenuated viruses. | Measles, mumps, rubella. |

| Allergy shots | Acceptable | Alteration in maintenance dose may be necessary. |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Modified from Hueston WJ, Eolers GM, King DE, McGlaughlin VG. Common questions patients ask during pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 1995;51:1465-1470.

Infections in Pregnancy

Syphilis

Pregnancy has little effect on the course of syphilis, but syphilis has a substantial effect on pregnancy and the fetus. Stages with spirochetemia are the most deleterious for the fetus. This is most often seen in late primary syphilis and in secondary syphilis. An increase in miscarriage, hydrops fetalis, stillborn, and preterm delivery of an infected fetus can be seen. Penicillin is the only antibiotic currently recommended for syphilis treatment in pregnancy because of its safety, efficacy, and transplacental passage to treat the fetus (CDC, 1999). Penicillin-allergic women should undergo desensitization first. Whenever treatment adequacy is questioned in pregnancy, repeat therapy should occur because congenital syphilis is a preventable disorder. All women with syphilis should be carefully evaluated for other STDs, in particular HIV, as the treatment and surveillance is different in co-infection and the possibility of neurosyphilis must be carefully evaluated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree