Chapter 12 Nonsurgical Treatment of Acute and Chronic Ankle Instability

Acute Ligament Injuries

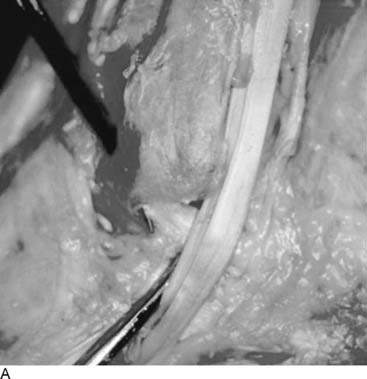

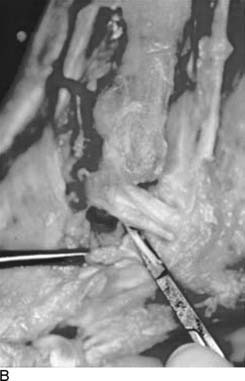

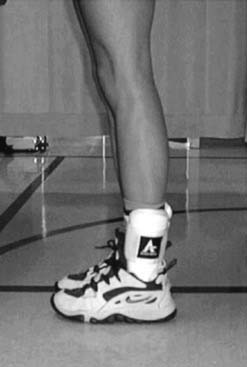

It has been shown in several studies that early diagnosis, functional treatment, and rehabilitation are the keys to prevention of chronic lateral ligament instability of the ankle.1–3 The on-field treatment of fresh ruptures is well known, for example, the rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) principle. The most vulnerable of the lateral ligaments is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL; Fig. 12-1, A), followed by a combined rupture of this ligament and the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL; Fig. 12-1, B). Other injuries, such as injuries to the medial deltoid ligament are much less frequent and occur with a frequency of less than 10% of all injuries.2,3 The mechanism of injury to the lateral ligaments is most commonly a plantarflexion inversion injury from landing (Fig. 12-2). Prevention of ligament injuries has gained much attention recently, because it has been shown that approximately 75% of all injuries are recurrences and may thus potentially be prevented, provided a sound protocol is used.4–6 Prevention by either coordination training using balance boards or by external support can significantly reduce the number of ligament injuries. Ankle tape and/or functional splinting, proficiently completed by the use of a stirrup splint (Fig. 12-3) is preferred by many athletes. It also has been shown that there is hardly any place for surgical repair after acute ligament ruptures.7,8 After the recommended treatment using a rehabilitation program with functional treatment, active range of motion exercises, coordination training, peroneal strengthening, and early weight bearing, the functional results are reported as excellent or good in approximately 80% to 90%, whereas 10% to 20% of patients develop secondary symptoms of chronic instability and/or pain.9,10 Despite this, the treatment of acute lateral ankle ligament injuries is still controversial; some authors have recommended that these injuries be treated with early mobilization, whereas others recommend cast or brace immobilization for 3 to 6 weeks or even early surgical repair. However, even though there is substantial evidence to suggest that early mobilization with active rehabilitation probably is the treatment of choice, there are only a few randomized, controlled studies comparing different treatment modalities.11 In a recent meta-analysis it was shown that no treatment of lateral ankle ligament ruptures led to an increased number of residual symptoms.12 Surgical treatment produced better results than functional treatment; however, functional treatment was found to be superior to cast immobilization for 6 weeks. The authors pointed out that surgical treatment was associated with higher costs, as well as increased risk of complications, such as disturbance of wound healing, nerve damage, and possibly infections. In one Cochrane review, it has been shown that functional treatment appears to be the favorable strategy for treating acute ankle ligament injuries when compared with immobilization.13 Concerning surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for acute injuries of the ligament complex, there is insufficient scientific evidence from randomized, controlled studies to determine the relative effectiveness of surgical and conservative treatment of these injuries, as concluded in a second Cochrane review.14 This might imply that surgical treatment is not necessarily superior. It also is obvious that in case of failed conservative treatment, late reconstructive procedures can be performed with satisfactory results, even several years after the initial injury. The extent of injury, that is, being grade I, II, or III, might play a role. Two prospective, randomized studies have evaluated the effect of early range of motion training, full early weight bearing, combined with either an ankle stirrup brace or specially designed compression pads. Both studies showed that early functional treatment resulted in significantly shorter sick leave and facilitated earlier return to sports, without the risk of inferior functional results in the long term. One Cochrane review compared different functional treatment strategies for the treatment of acute ankle ligament injuries.15 It was shown that the use of elastic bandage was correlated with fewer complications than tape but was associated with slower return to work and sport. Semirigid ankle braces produced less ankle laxity than elastic bandages. Lace-up ankle support was more effective in reducing swelling in the short term compared with semirigid braces, elastic bandage, and tape. Thus either semirigid brace or lace-up support probably is preferred.

Figure 12-3 Ankle stirrup brace used in rehabilitation after acute and chronic lateral ankle instability.

It appears that early weight training, combined with range of motion training, is beneficial. The long-term prognosis likely is unaffected by early functional training.16,17 Studies have shown that the best external support is strong evertor muscles. Therefore a combination of isokinetic strength training with proprioception training is most favorable; this combination can shorten rehabilitation and serve as secondary prophylaxis.

Chronic Ankle Joint Instability

It has been shown in several studies that chronic lateral ankle joint instability may develop in approximately 10% to 30% of all patients who sustain an acute injury of the ligaments.18–20 The functional instability, irrespective of the mechanical laxity (indeed, there is no constant correlation between the functional instability and the laxity of the joint), does not always produce disability of such grade that surgical reconstruction is needed. Surgical reconstructions have been well described during the last 3 decades and are needed most often in athletes who participate in sports with high demands of stable ankle joints, such as soccer, volleyball, basketball, and all sports involving jumping, sidestepping, turning, and twisting. In the literature, more than 50 different surgical methods have been described to correct chronic ankle joint instability.4,6,9,10,19 The clinical diagnosis initially is based on a thorough clinical assessment, for instance, testing the anterior drawer sign (Fig. 12-4) and the inversion (supination) test (Fig. 12-5). Comparison always must be made with the contralateral ankle. It must be remembered, however, that functional instability is a complex syndrome, and there are several factors at play, such as increased laxity, proprioceptive deficit, and peroneal muscle weakness, either alone or most often in combination. Excessive laxity must be corrected with some kind of surgical procedure, but proprioceptive deficit and muscular weakness can and should be treated by rehabilitation.20 In the acute phase the main objective is for pain relief, but soon after injury the treatment is aimed at restoring range of motion, and this should be done without any loss of proprioception.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree