Chapter 50 Nicotine Addiction

Overview

For tobacco-dependent persons, craving results when nicotine occupancy on receptors declines over time (e.g., during sleep at night). Relief from craving requires that the smoker replenish the nicotine within the receptor as completely as possible, which is why the first cigarette of the morning is often the most “satisfying” to addicted smokers. Since the cigarette is the most efficient rapid-delivery device for nicotine and the concurrent relief of craving, physicians and patients need to understand that medicinal nicotine replacement products are quite inefficient, by comparison, delivering lower concentrations of nicotine and incompletely resolving cravings.

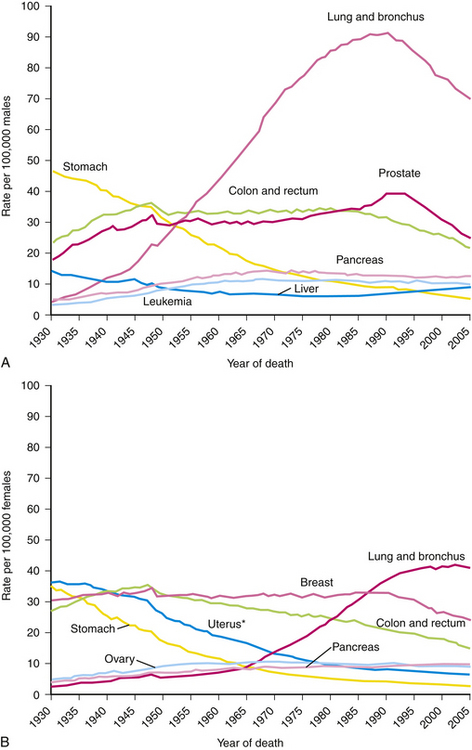

Tobacco contributes to about 443,000 deaths annually in the United States and has rightly been dubbed the “leading cause of death in the United States” (McGinnis and Foege, 1993; Mokdad et al., 2004). One third of these smoking-related deaths are from cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular accident (CVA, stroke), 29% from lung cancer, 20% from chronic respiratory disease, and at least 8% from cancers other than lung (Fig. 50-1). Just over 10% of deaths attributable to smoking occur in nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke, most from cardiovascular causes (CDC, 2008). Each year, smoking is responsible for 18% of the total deaths in the United States—seven times more Americans than were killed in the Vietnam War. Smoking has killed more Americans during the 20th century than were killed in battle or died of war-related diseases in all U.S. wars ever fought (Pollin and Ravenholt, 1984). Furthermore, cigarettes kill more Americans than alcohol, car accidents, suicide, AIDS, homicide, and illegal drugs combined (ACS, 2005).

Figure 50-1 Deaths attributable each year to smoking.

(From CDC Office on Smoking and Health. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/tables/index.htm.)

Health Risks Associated with Smoking

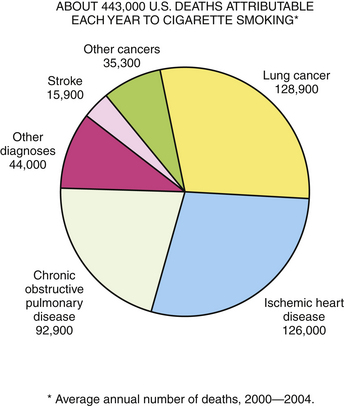

Cancer

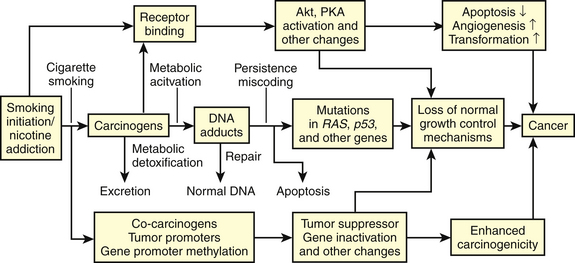

About 30% of all cancer deaths are attributable to cigarette smoking, with the evidence increasingly stronger. Box 50-1 lists diseases, including many cancers, for which the evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship, as well as those for which the evidence is sufficient only to suggest a causal relationship. Reviewing tobacco’s role in carcinogenesis, Hecht (2008) discusses several mechanisms that contribute to cancer, including metabolic changes in DNA and formation of DNA-carcinogen adducts, leading to mutation; inhibition of genes such as p53, a tumor suppressor; and mutations in the K-RAS oncogene (Fig. 50-2).

Box 50-1 Evidence-Based Relationship between Smoking and Disease

From US Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking: a Report of the Surgeon General, 2004. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, 2004.

The evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship between smoking and:

Figure 50-2 Mechanisms that contribute to tobacco-caused cancer.

(From American Chemical Society, for Stephen S. Hecht. Progress and Challenges in Selected Areas of Tobacco Carcinogenesis.)

Lung

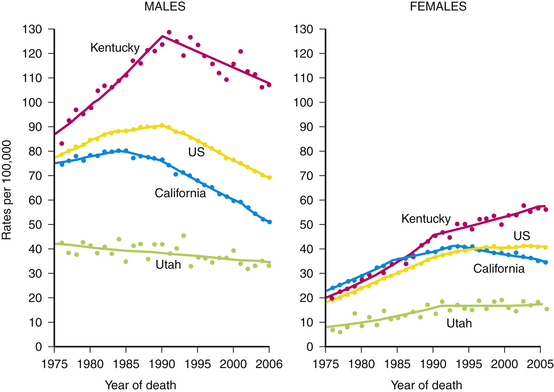

A clear dose-response relationship exists between lung cancer risk and daily cigarette consumption. From 1950 to 1990, the U.S. mortality rate for lung cancer increased fourfold for men and sevenfold for women. Although the mortality rates in men have been declining since 1990, lung cancer is still the principal cause of cancer death for both genders. In 1988, lung cancer passed breast cancer as the leading cause of death from cancer in women (Fig. 50-3). Although the lung cancer death rate has leveled off in U.S. women, in some states it is still increasing (Fig. 50-4).

Unfortunately, early detection does not improve the survival rate for lung cancer. The 5-year survival rate is only 15% and has improved only slightly since the early 1960s (ACS, 2005). Almost 60% of lung cancer patients die within a year and 85% within 5 years. By the time the diagnosis is made, three of four patients already have metastases. However, the risk of death from lung cancer is substantially reduced when smoking is discontinued. Reducing smoking from an average of 20 cigarettes a day to less than 10 per day reduces the lung cancer risk by 25% (Godtfredsen et al., 2005). A diminished risk for lung cancer is experienced in former smokers after 5 years of cessation; however, the risk remains higher than that of nonsmokers for as long as 15 to 20 years (US Surgeon General, 2004).

Pancreas

An equally dismal picture occurs with cancer of the pancreas, for which the 5-year survival rate is only 2%. Because of the nonspecific nature of the initial symptoms and the difficulty in making a diagnosis, the mean survival time after diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is less than 6 months. Smokers have two to three times the risk of pancreatic cancer as nonsmokers, and the risk is proportional to the amount smoked. Increased risk persists at least 10 years after quitting. More than one fourth of pancreatic cancer cases (27%) are attributable to cigarette smoking (Silverman et al., 1994; US Surgeon General, 2004).

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Changes in bronchi and the lung parenchyma are proportional to duration and intensity of smoking. Cigarette smoke inhibits ciliary activity of the bronchial epithelium and phagocytic activity of macrophages in the alveoli, resulting in decreased clearance of foreign material and bacteria from the lung, which leads to increased infection and tissue destruction. Smoking also releases inflammatory mediators, including oxidases and proteases, and inhibits pulmonary repair mechanisms. Even after age 60, smokers who quit have better pulmonary function than those who continue smoking. Lung function is inversely related to the number of cigarettes smoked over a lifetime. The rate of decline in pulmonary function is arrested by smoking cessation, the earlier the better.

Cardiovascular Disease

Stroke (Cerebrovascular Accident)

The risk of stroke increases in proportion to the amount of smoking. Those who smoke more than 40 cigarettes/day have twice the stroke risk of those who smoke less than 10 cigarettes/day. Compared with women who have never smoked, the risk of stroke increases 2.2-fold in women smoking 1 to 14 cigarettes/day and 3.7-fold in women smoking 25 or more cigarettes/day (Colditz et al., 1988). Noting a clear dose-response relationship, Bonita and associates (1986) found a threefold increase in the risk of stroke in smokers versus nonsmokers (see eFig. 50-1 online). The risk is 5.6 times higher in persons smoking more than one pack daily. Cigarette smokers who are also hypertensive have a 20-fold increased risk of stroke (US Surgeon General, 2004).

Other Diseases and Conditions

Wrinkles

We are not very effective in getting the message about tobacco’s hazards across to adolescents. By talking about disease, we may not be speaking their language. The fact that smoking causes wrinkles, bad breath, and yellow teeth may be a more effective message than evidence that smoking kills. Premature wrinkling (crow’s feet) increases with the number of cigarettes smoked; heavy smokers are five times more likely to have wrinkles than nonsmokers (Kadunce et al., 1991).

Electronic Cigarettes

In 2009 the U.S. Congress granted the FDA the power to regulate tobacco products, including the authority to stop e-cigarettes from entering the country. Electronic cigarettes, even though smokeless, may contain known carcinogens and toxic chemicals. There is considerable debate as to whether these products might deliver nicotine with minimal additional harm to the smoker, becoming a “harm reduction” instrument that enables smokers to continue their nicotine dependence and reduce risk or enhance quit attempts. On the other hand, these products have little quality control; nicotine delivery is inconsistent; FDA-type testing has not yet been done; and long-term risks are not known.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree