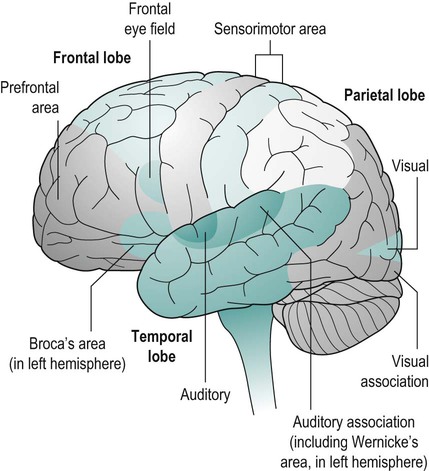

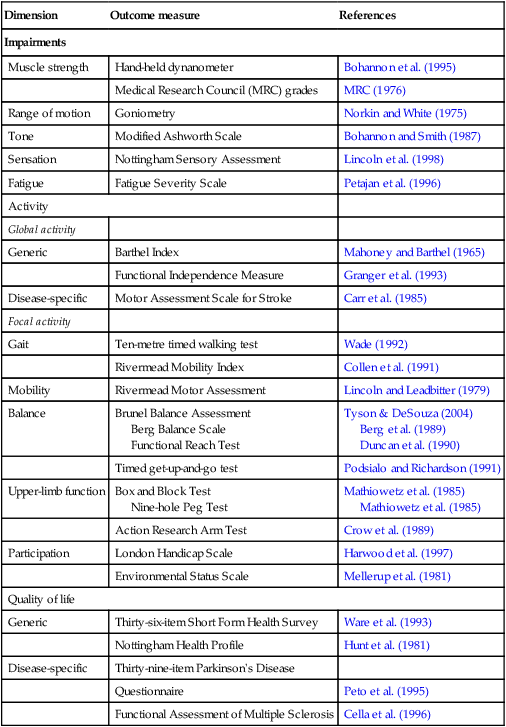

An emerging evidence base surrounding the issues of neurological rehabilitation means that the role of the physiotherapist in treating and managing neurological conditions is developing. Current research identifies the importance of task-specific, strength and repetitive training. Alongside this the use of novel interventions, such as functional electrical stimulation (FES) and constraint-induced movement therapy (CiMT) are advocated. Research has shown that no one treatment approach is superior to any other; instead, practitioners need to select the most appropriate intervention based on the available evidence base. Neurological damage can result in the disruption of normal physical, psychological, cognitive and social functions, which reinforces the need for a collaborative and co-ordinated approach from a wide range of rehabilitation professionals. It is vital that a truly holistic approach to the management and treatment of patients and their families be adopted, with clinical reasoning and problem-solving at its centre. Practitioners need to understand both the patients’ and carers’ perspective. Research has shown that therapists’ and patients’ goals often differ. As such, measurement of outcome is an important aspect of neurological rehabilitation. The chapter provides a section on outcome measurement and goal-setting in relation to the International Classification of Function (ICF) framework set out by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001. The most appropriate measures have been selected based on their psychometric properties. Readers should refer to Tyson et al. (2008) for further information. This chapter begins by outlining the principal causes of neurological damage and then describes types of movement disorders and the most frequently encountered clinical features. The clinical features have been grouped together into categories to aid cross reference within the assessment process. Physiotherapy assessment and the main evidence-based interventions are then discussed in relation to present-day clinical practice. A new section on promising interventions that use rehabilitation technologies has been included to demonstrate their growing use in healthcare practice. The chapter concludes with an overview of the more commonly known neurological conditions, namely stroke, multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease and traumatic brain injury (Figure 26.1). These sections are not intended to be exhaustive and readers can consult the lists of further recommended reading at the end of the chapter. The result of abnormal tone, altered motor control and impaired sensory input will lead to what is known as a movement disorder. Day-to-day functions, such as walking, dressing and eating, become difficult to perform owing to movements becoming un-coordinated, uncontrollable and involuntary. Common movement disorders are listed below and can be seen with conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s (see Chapter 24). • Muscle weakness and/or atrophy – a reduction in muscle strength of a single muscle or groups of muscles. Weakness can be specific to a side, such as hemiplegia, or be generalised as a result of a person no longer performing physical activities (deconditioned). Atrophy describes muscle loss owing to lack of use. • Muscle tone – this is the ‘state of readiness’ of an individual’s muscles at rest. It is vital for maintaining posture. The continuous small adjustments of the muscle sensory receptors (muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs (GTOs) prepare the muscles for movement). Muscle tone can become increased (hypertonic) or decreased (hypotonic) depending on the amount of information being sent to the muscle receptors. This means that damage to the CNS can result in altered muscle tone. • Spasticity – is ‘a motor disorder, characterised by a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes (muscle tone) with exaggerated tendon jerks, resulting from hyper-excitability of the stretch reflex as one component of the upper motor neurone (UMN) syndrome’ (Lance 1980). • Hypotonia – is low muscle tone. Muscle receptors are unprepared for movement resulting in resistance-free movement and weakness of muscles. • Rigidity – is an increase in muscle tone which leads to a resistance in passive movement. There are two types commonly found in Parkinson’s: • altered cutaneous sensation – the skin sensation can become diminished (anaesthesia), absent (parasthesia) or more sensitive (hyperaesthesia) to inputs such as light and deep touch, pressure, vibration and two-point discrimination; • altered proprioception – the muscle sensory receptors (muscle spindles and GTOs) are unable to provide information about a joint’s position. This means that an individual may be unable to recognise what position a body part is in; • pain – damage to nerve endings and/or pain pathways, as well as pain caused by secondary complications, such as malalignment of joints (owing to swelling or poor positioning of soft tissue structures) will result in pain. • dysarthria – a difficulty in articulating words owing to muscle weakness or lack of co-ordination producing slurred speech; • dysphasia (expressive and receptive) – the processing part of speech is affected. Individuals can have difficulty saying what they want (expressive) or understanding what the word means (receptive). The main purpose of the clinical examination is to gather information about the patient’s movement disorder and level of functional ability (Freeman 2002). Initially, observe the patient and try to draw conclusions about what they are able to do unaided. It is important to remember that at no point must the patient be put at risk. It is part of the physiotherapist’s role to ‘risk assess’ what is reasonable to allow the patient to attempt independently and what they need help with in order to be safe. Objective assessment should include assessment of active and passive range of movement and strength. This will guide observation of posture and movement analysis in sitting, lying to sitting, sit-to-stand, transferring from bed to chair, standing and walking, etc. The exact activities observed and/or assisted will depend on the level of ability of the patient. Once the patient has been given the opportunity to demonstrate what they can do unaided, assistance can then be given to ascertain what the person can achieve with help. This is where assessment and treatment begin to merge into one and the same thing. The assessment begins when initial contact is made. For instance, observing the person’s gait when they walk into the room often gives a more accurate picture of functional gait pattern than when the person is asked to walk while being watched. The WHO provides a useful framework and common terminology for describing and measuring the consequences of disease and the impact that rehabilitation may have on them (Edwards 2002). This is the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, known more commonly as ICF, which provides a standard language and framework for the description of health and health-related states. This describes changes in body function and structure (impairment), what a person with a health condition can do (their level of ability), as well as what they actually do in their usual environment (their level of participation). • ‘Body function’ considers the loss or abnormality of body structure, or of a physiological or psychological function. • ‘Activity’ refers to the nature and extent of functioning at the level of the person. It may be limited in nature, duration or quality. It considers if a person can do a task and how well they do it. • ‘Participation’ refers to the nature and extent of a person’s involvement in life situations in relation to impairment, activities, health conditions and contextual factors. Research by the Greater Manchester Outcome Measures Project team identified the domains that physiotherapists need to measure during clinical assessment in neurological patients using the ICF as a framework. (Tyson et al. 2008). They suggested neurological assessments should include assessment of: Impairments (problems in body functions or structures) • balance impairment: postural sway • posture impairment: alignment, weight distribution • range of movement/contracture • sensation and proprioception • walking impairment: speed, endurance, step length, cadence, etc. Activities (ability an individual has in executing activities) • balance activity – sitting, standing, dynamic, supported, assisted • mobility activity – bed mobility, sit-to-stand, transfers, walking, stairs/steps, etc. • upper limb activity – grips/grasps, dexterity, activities of everyday life • walking activity – in/outdoor, assistance, use of equipment, independence. Measurement implies the quantification of data in either absolute or relative terms. Determining the effectiveness of an intervention by measuring its effect on an outcome provides the basis for evidence-based healthcare (Edwards 2002). Outcome measures take the guesswork and subjectivity out of evaluation and can assist the physiotherapist in proving clinical effectiveness. • deciding what needs to be measured; • selecting the appropriate outcome measure; • does it measure what you want it to measure (reliability, validity and sensitivity)?; For a discussion of outcome measurement theory and properties in rehabilitation, we refer the reader to Finch et al. (2002). Physiotherapy outcome measures should be considered in the wider context of rehabilitation. Rehabilitation can be considered a problem-solving and educational process aimed at reducing disability and enhancing function in people who are affected by disease (Wade 1992). Rehabilitation principles are based upon the enhancement of activity by restoring skills and capabilities through functional retraining and environmental adaptation. Rehabilitation promotes independence and aims to facilitate the fullest potential physically, psychologically, socially and vocationally for a patient. Rehabilitation involves the recovery or improvement of function, as well as prevention of disability and the maintenance of a social role. Table 26.1 provides a summary of the outcome measures commonly used within neurology. It is not meant to be comprehensive and the reader is directed to the ‘Further reading’ list at the end of the chapter. Table 26.1 Outcome measures frequently used within the clinical setting The planning of goals is necessary to ensure that the rehabilitation effort is as effective and efficient as possible (Elsworth et al. 1999). Outcome is better if the goals involve the patient, are challenging and are set at different levels. The evidence relating to goal-setting is limited, but there is a general trend towards the inclusion of goal-setting in the rehabilitation process (Wade 1999c). With the emphasis on patient-centred care and inclusion of the patient in the decision-making processes, a formal process of goal planning will help to improve the co-ordination and co-operation of all those people involved. Co-operative goal setting makes the process of rehabilitation more patient-focussed and helps to motivate the patient through the long period of rehabilitation and beyond. In other words the effects of treatment will be long-lasting and continue to be evident when treatment has ceased. 1. Set meaningful and challenging but achievable goals. 2. Involve the patient and carers. 3. Include short- and long-term goals. 4. Set goals both at a team and an individual professional level. • medium-term goals = objectives; Wade (1999a) defines these terms as given in Table 26.2. Table 26.2 Adapted from Wade (1999b). In summary, goal-setting allows for the alignment of patient and professional goals. It is a method of ensuring that the rehabilitation team focusses on the needs of an individual patient and can help to motivate patients. It should lead to an overall improvement in treatment effectiveness and provide a method of measuring the effectiveness of treatment interventions (McGrath and Adams 1999; Edwards 2002). Now the assessment is complete, a problem and goals list needs to be formulated. It is important to bring the problems identified as a physiotherapist together with the patient’s/carer’s perceived problems. Problems and goals need to be agreed with the patient and family. At the end of the day it is important to remember that the goals should be the patient’s, not the physiotherapist’s (Table 26.3). Table 26.3 Systematic reviews of treatment interventions suggest that participants benefit from exercise programmes in which functional tasks are directly trained, with less benefit if the intervention is impairment-focussed (Van Peppen 2004). Examples of task-specific practice include practising sit-to-stand, walking and reaching activities, and are often mixed with other components, including strengthening and treadmill training. Many aspects of rehabilitation involve repetition of movement. Repeated motor practice has been hypothesised to reduce muscle weakness and spasticity (Feys 1998, Nuyens 2002), and to form the physiological basis of motor learning (Butefisch 1995), while sensorimotor coupling contributes to the adaptation and recovery of neuronal pathways (Bruce and Dobkin 2004). Active cognitive involvement, functional relevance and knowledge of performance are hypothesised to enhance learning (Carr and Shepherd 1987). Most research has been undertaken on patients with stroke. A Cochrane review, acknowledged as the best single source of evidence about the effects of healthcare interventions, has been undertaken on repetitive task training for improving functional ability after stroke (French et al. 2007). This showed repetitive task training resulted in modest improvement in lower limb function, but not upper limb function. Training may be sufficient to impact on daily living function. However, there is no evidence that improvements are sustained once training has ended. An evidence-based review of upper limb interventions found repetitive task-specific training may improve arm function (EBRSR 2009). Exercise (as covered in Chapter 13) includes stretching, strengthening and aerobic types of activities. If performed regularly with enough repetitions and appropriate duration these activities can develop into an exercise programme that will improve an individual’s range of movement, muscle strength and physical fitness. Current literature reviewing the effectiveness of these types of exercise now shows that strengthening exercises are beneficial to many types of neurological patients in the acute, rehabilitation and community settings (Weiss et al. 2000; Romberg et al. 2004). A Cochrane review suggested that aerobic exercise to develop physical fitness in stroke patients can improve their walking speed, tolerance and level of mobility (Saunders et al. 2009). The use of walking aids allows body weight to be supported but leads to an altered gait pattern, which can be tiring to maintain. Hoisting equipment allows a patient’s body weight to be partially supported while walking and a more normal gait pattern to be adopted. However, a large space is required to walk a patient with this type of equipment so intensity, distance and duration are low. The introduction of a treadmill, which provides a constant flat moving surface, gives patients the chance to walk greater distances without moving around a room and provides safety with the use of a partial body weight support (PBWS). This type of walking practice can reduce the number of therapists needed to walk a patient (Figure 26.2).

Neurological physiotherapy

Introduction

The fundamentals of CNS damage

Principal causes of neurological damage

Clinical features of damage to the CNS

Movement disorders

Impairments

Motor impairments

Sensory impairments

Communication disturbances/swallowing

Assessment of neurological patients

Objective assessment

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

Outcome measures

Outcome measures in context

Dimension

Outcome measure

References

Impairments

Muscle strength

Hand-held dynanometer

Bohannon et al. (1995)

Medical Research Council (MRC) grades

MRC (1976)

Range of motion

Goniometry

Norkin and White (1975)

Tone

Modified Ashworth Scale

Bohannon and Smith (1987)

Sensation

Nottingham Sensory Assessment

Lincoln et al. (1998)

Fatigue

Fatigue Severity Scale

Petajan et al. (1996)

Activity

Global activity

Generic

Barthel Index

Mahoney and Barthel (1965)

Functional Independence Measure

Granger et al. (1993)

Disease-specific

Motor Assessment Scale for Stroke

Carr et al. (1985)

Focal activity

Gait

Ten-metre timed walking test

Wade (1992)

Rivermead Mobility Index

Collen et al. (1991)

Mobility

Rivermead Motor Assessment

Lincoln and Leadbitter (1979)

Balance

Brunel Balance Assessment

Berg Balance Scale

Functional Reach Test

Tyson & DeSouza (2004)

Berg et al. (1989)

Duncan et al. (1990)

Timed get-up-and-go test

Podsialo and Richardson (1991)

Upper-limb function

Box and Block Test

Nine-hole Peg Test

Mathiowetz et al. (1985)

Mathiowetz et al. (1985)

Action Research Arm Test

Crow et al. (1989)

Participation

London Handicap Scale

Harwood et al. (1997)

Environmental Status Scale

Mellerup et al. (1981)

Quality of life

Generic

Thirty-six-item Short Form Health Survey

Ware et al. (1993)

Nottingham Health Profile

Hunt et al. (1981)

Disease-specific

Thirty-nine-item Parkinson’s Disease

Questionnaire

Peto et al. (1995)

Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis

Cella et al. (1996)

Goal-setting

Describes a state

Aim

Is for the patient and family

Is in terms of a social role or functioning or well-being

Objective

Is set within the medium term

Involves direction of change as much as achieving a specific state

Is framed in terms of patient behaviour and environment

Target

Is set within the short term

Is specific and often involves only one named person/profession

May be set at any level or in terms of the rehabilitation process

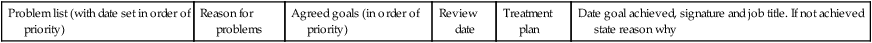

List of problems and goals

Problem list (with date set in order of priority)

Reason for problems

Agreed goals (in order of priority)

Review date

Treatment plan

Date goal achieved, signature and job title. If not achieved state reason why

Interventions

Task-specific practice

How the intervention might work

Evidence

Exercise

Treadmill training

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neurological physiotherapy