Mini-ALIF

Thomas A. Zdeblick

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indications

In selected patients, anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) is indicated for the treatment of symptomatic degenerative discs. Additional indications include pseudoarthrosis, spondylolisthesis (either isthmic or degenerative), lateral listhesis, and scoliosis. These deformity indications are typically coupled with posterior instrumentation as well. Although every case must be individualized, certain generalizations regarding indications can be made. Appropriate symptoms of degenerative disc disease include an aching low back pain that is typically present in the midline and over the sacroiliac joints after activity. On occasion, radiation into the buttocks may occur. Plain radiographs typically show loss of disc space height, endplate sclerosis, endplate osteophytes, and loss of lordosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans typically show loss of disc hydration and peri-endplate edema. Annular tears or a high-intensity zone is not sufficient in most cases to warrant fusion. Discography, although controversial, may be utilized to confirm a concordant pain response.

ALIF procedures are typically indicated for one- or, rarely, two-level disc degeneration. Clinical results, at least for fusion, of three-level or more procedures have been less than ideal. In my practice, I limit the indications for ALIF for disc degeneration to patients younger than 65. There are several reasons for this. As patients become older, osteoporosis and thinning of the endplates occur. This makes interbody devices less stable. Also, the retraction of the great vessels required for anterior lumbar spine exposure poses a greater risk to the older patient. Complications such as embolism, thrombosis, leg ischemia, and swelling are more common in older patients.

Postdiscectomy collapse is an excellent indication for ALIF. In these cases, however, the surgeon should expect to find a greater amount of adhesion surrounding the anterior annulus. Prior disc space infection is not necessarily a contraindication, as long as the infection has been adequately treated and systemic markers have returned to normal.

Isthmic spondylolisthesis is best reduced via ALIF. Following complete discectomy, sequential distracters placed within the disc space provide excellent mechanical force to reduce the translational deformity. Indirectly, foraminal stenosis is decompressed as well via distraction. Posterior instrumentation is typically placed following reduction. In cases with disc collapse and spondylolisthesis, stand-alone ALIF may be indicated.

In long deformity constructs ending at the sacrum, many surgeons prefer ALIF at the L5-S1 junction to improve fusion rate and prevent distal hardware failure. ALIF also works quite well to treat pseudoarthrosis of poster lumbar fusions. The large surface area and excellent vascular supply of the vertebral endplates readily enable fusion healing.

Contraindications

The placement of anterior cages is contraindicated with active infection. Although anterior approach and débridement with bone grafting can be performed in cases of active infection, metallic implants are not recommended. Stand-alone ALIF procedures are not recommended in cases of osteoporosis or osteopenia with thinning of the endplates. Previous anterior spinal surgery is a relative contraindication due to the presence of adhesions along the great vessels, which makes

their dissection much more difficult. These cases must be individualized. Other previous abdominal surgery is not a contraindication to this approach. Midline incisions for laparotomy or Pfannenstiel incisions for gynecologic procedures have not proved to be a contraindication to the mini-open approach. Prior retroperitoneal radiation treatment is a contraindication. Extensile abdominal wall reconstruction, however—for instance, mesh repair of hernia—does make the approach much more difficult. Morbid obesity is a contraindication.

their dissection much more difficult. These cases must be individualized. Other previous abdominal surgery is not a contraindication to this approach. Midline incisions for laparotomy or Pfannenstiel incisions for gynecologic procedures have not proved to be a contraindication to the mini-open approach. Prior retroperitoneal radiation treatment is a contraindication. Extensile abdominal wall reconstruction, however—for instance, mesh repair of hernia—does make the approach much more difficult. Morbid obesity is a contraindication.

TECHNIQUE

The patient is positioned supine on the operative table. I do not place a lumbar bolster to hyperextend the spine. I find this can lead to foraminal compression or, rarely, femoral nerve palsy. A radiolucent operating table is utilized, the patient is placed in slight Trendelenburg position, and I often roll the table toward the right during the approach. This helps facilitate the retraction of the peritoneal contents from left to right. All patients undergoing ALIF receive a mild bowel preparation the night before surgery. This consists of a single enema and one bottle of GoLYTELY. This not only helps during the retraction but also helps prevent postoperative ileus. I have found that a bowel preparation given preoperatively greatly facilitates early patient discharge.

The appropriate level for skin incision is marked under guidance of both anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopy (Fig. 27-1A). Using the lateral view, the surgeon marks on the anterior abdomen the direct line of extension from the disc space to be operated upon. If a two-level procedure is performed, the incision is centered between the two levels but closer to the more inferior of the two disc spaces. For single-level procedures, a 6- to 7-cm transverse skin incision is utilized. For two-level procedures, a 9- or 10-cm oblique incision is made. Alternatively, a paramedian vertical skin incision can be used as well. I prefer the horizontal skin incision purely for cosmetic reasons. I typically stand on the patient’s right side, working toward myself for the left-to-right exposure. The fluoroscopy equipment is brought in and left in place superior to the surgeon (Fig. 27-1B).

L5-S1 Exposure

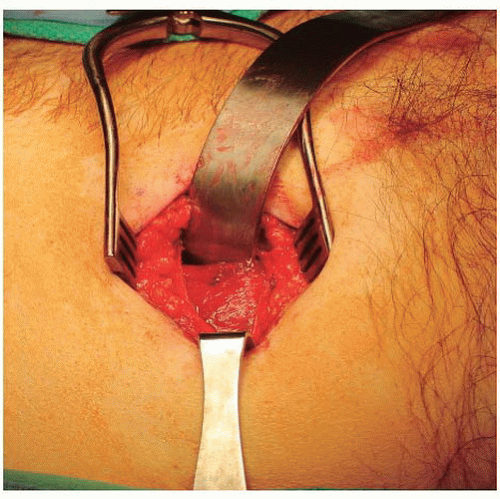

A 7-cm transverse skin incision is made beginning 1 cm to the right of midline and extending 6 cm to the left of the midline. Fluoroscopy is used to locate this incision. Typically, for L5-S1, this incision is located two to three fingerbreadths above the pubic symphysis. Sharp dissection is carried out through skin and subcutaneous tissue, and the anterior rectus sheath is exposed. The anterior rectus sheath is incised transversely with a no. 10 blade (Fig. 27-2). Alternatively, this can be incised vertically paramedian. Care is taken not to disturb the muscle fibers lying beneath. The midline between the heads of the rectus muscle is then located using blunt dissection. Using Kitner dissectors and a finger and working from the midline, the surgeon develops the preperitoneal space underlying the left rectus muscle (Figs. 27-3 and 27-4). A small finger retractor is slipped under the rectus muscle, and it is elevated. The surgeon can now bluntly dissect underneath the rectus muscle, along the posterior rectus sheath, until the arcuate line is palpated inferiorly and laterally.

Blunt dissection inferior to the arcuate line allows entry into the retroperitoneal space. For more extensile exposure, the posterior rectus sheath can be divided superiorly from the arcuate line. This must be done carefully, with scissors, as the peritoneum is tightly bound to the posterior sheath. A thin Deaver retractor is then slipped into this space, and the peritoneum is retracted from left to right. The peritoneal reflection along the lateral abdominal wall must be mobilized bluntly using Kitner in a “paddling” fashion. The left ureter is then identified, which ensures that the surgeon is indeed operating within the retroperitoneal space. Typically, I retract the ureter along with the peritoneum in a left-to-right direction. Blunt dissection alone is continued until the promontory of the sacrum is palpable. The Deaver retractor is then placed into a mechanical holder to ensure that the peritoneum is maintained in its position.

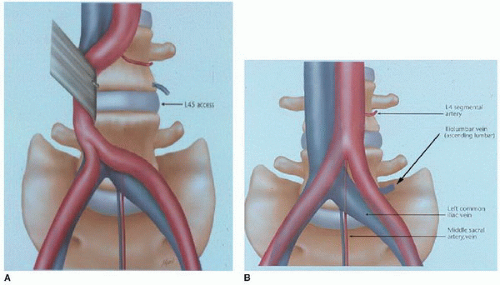

Complete exposure of the L5-S1 disc space requires mobilization of the left common iliac vein and the middle sacral artery and vein (Fig. 27-5A and B). This must be done without disturbing the presacral plexus of nerves. Often these nerves are visible. They run vertically across the disc space in a plane that is superficial to that of the middle sacral artery and vein. I begin by bluntly dissecting this presacral plexus of nerves from left to right across the disc space. No cautery or bipolar should be used while this nervous plexus is mobilized. The middle sacral artery and vein lie in a plane directly adherent to the anterior annulus.

FIGURE 27-3 The preperitoneal space is developed in the space underlying the left rectus abdominis muscle. This is done with Kitner dissectors and finger dissection. |

Typically, there are two veins and a single artery. Care should be taken while these are mobilized, to make sure that they are not mistaken for the presacral nervous plexus (Fig. 27-5C). These vessels are mobilized with a fine right-angled dissector and clips applied and then divided. Cautery must be avoided. Blunt dissection with Kitner elevators can then be performed across the disc space. I typically expose the left side of the disc space first. This requires elevation of the left common iliac vein. This vein must be carefully mobilized with Kitner elevators.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|