Metabolic Bone Disease

Steven J. Fitzgerald and David G. Lewallen

Key Points

Paget’s Disease

Introduction

Paget’s disease affects 1% of the U.S. population over the age of 40.1 It is a chronic localized disorder of bone marked by increased bone turnover, specifically, resorption, formation, and remodeling resulting in the replacement of normal matrix with a weakened and enlarged bone. Both monostotic and polyostotic forms are possible as defined by the number of involved skeletal sites. Paget’s can affect any bone but is most common in the pelvis and femur, and is polyostotic in 76% of cases.2–5 Overall prevalence, including both forms, increases with age, with a 1.2 : 1 male-to-female ratio in the United States.1 Prevalence varies geographically; Paget’s is most common in Europe among those of Anglo-Saxon ancestry and is rare in Africa and Asia.6,7 Population studies from both Europe and New Zealand have suggested that the severity of Paget’s disease has decreased over the past 40 years, and an increase in the monostotic form of the disease has been noted, especially among women.8,9

Pathoanatomy

Paget’s disease is often diagnosed incidentally but can present with generalized bone pain. With proximal femoral and hip involvement, it can be difficult to differentiate generalized bone pain from active disease, stress fracture, or radiculopathy from intra-articular pathology. Intra-articular injection in this situation may aid in differentiating the source of pain.10 Malignant transformation and Paget’s sarcoma occur in less than 1% of patients but carry a poor prognosis and should be included in the differential when symptomatic patients with Paget’s disease of the hip are evaluated.11 Destructive bone changes and a soft tissue mass superimposed on typical pagetoid bone patterns with recently increased pain may suggest possible sarcomatous change.

Bone pain generally correlates with disease activity. Disease activity can be followed by monitoring of serum alkaline phosphatase and urinary pyridinium cross-links. Increased bone turnover results in increased excretion of type I collagen breakdown products, and the compensatory osteoblastic activity results in increased alkaline phosphatase activity.

The exact cause of Paget’s remains unknown; however, a viral origin was first proposed in 1974, after the discovery of virus-like inclusion bodies in the osteoclasts of affected bone.12 A viral cause continues to be a focus of current research, with implications for the paramyxovirus family.13 Multiple molecular markers have also been implicated in the disease process, including interleukin-6, a resorptive cytokine found in the bone marrow of affected patients.14 Additional work has been undertaken to investigate increased expression of genes that inhibit apoptosis, which leads to a relative increase in the number of osteoclasts.15 It is more common among relatives of those with Paget’s disease, with first-degree relatives having a seven-fold increased chance of developing Paget’s disease.16 Genetic studies and linkage analysis have implicated the sequestrosome 1 gene and multiple other genetic loci as candidate regions for Paget’s disease.15,17 Extensive osteolysis, large numbers of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, and rapid formation of disorganized woven bone remain the histologic hallmarks of pagetoid bone.18

A frequent association with disabling hip disease leading to hip arthroplasty has been well established, but it remains unclear whether osteoarthritis is more common in patients with Paget’s disease than in age-matched controls.4,19,20 It has been postulated that the pagetic process and deformity predispose patients to develop degenerative arthritis at an accelerated rate secondary to juxta-articular bony enlargement, resulting in incongruity, altered biomechanics secondary to bowing, and altered subchondral support.21–23

In the region of the hip, characteristic varus bowing of the femur, coxa vara, and acetabular protrusio are commonly seen in patients with Paget’s. Subcapital fracture, nonunion of the proximal femur, and a distorted and sclerotic canal can complicate treatment. Both medial and concentric wear patterns of the hip joint are common23,24 (Fig. 78-1). Hypervascularity characteristic of the active lytic phase of the disease may be associated with increased intraoperative blood loss. Appropriate medical management, including consultation with an endocrinologist, can help mitigate the risk of intraoperative bleeding, as well as postoperative peri-implant bone resorption.

Figure 78-1 Typical acetabular wear pattern seen in Paget’s disease.

Alternative Treatment

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used to reduce bone pain in patients with active disease; however, antiresorptive medications have become the mainstay of modern medical treatment of Paget’s disease of bone. Antiresorptive medications act by decreasing the osteoclast-mediated bone resorption characteristic of Paget’s disease, both by decreasing active symptoms and reducing future complications. Two main classes of antiresorptive medications are available in the United States: (1) calcitonin and (2) bisphosphonates. Salmon calcitonin is less effective than nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates and requires daily subcutaneous injection.25 The nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates alendronate, risedronate, and zoledronate acid have all shown varying degrees of effectiveness and potency when serum alkaline phosphatase levels are used as measurement of active disease.25,26 Zoledronate has proved particularly effective in arresting active disease and provides the convenience of one-time intravenous dosing over 15 minutes.26 A summary of commonly used bisphosphosphonates and dosing regimens is provided in Table 78-1. Antiresorptive therapy can be used to treat pain caused by Paget’s disease and to prevent or slow the development of osteoarthritis and advancing deformity. Antiresorptive therapy is also thought to be effective before surgery for reducing intraoperative bleeding due to hypervascularity in active disease, as well as the potential for postoperative bone resorption.25–29 No consensus is seen in the literature regarding the timing of perioperative bisphosphonate therapy. The timing and dosing of antiresorptive therapy should be prescribed in consultation with and monitored by an endocrinologist secondary to potential side effects.21 Nonsurgical treatment of degenerative arthritis associated with Paget’s disease is the same as that provided for idiopathic osteoarthritis and includes anti-inflammatory agents, activity modification, and gait aids.

Table 78-1

Antiresorptive Agents for Paget’s Disease of Bone

| Agent | Trade Name | Dosage |

| Risedronate | Actonel | 30 mg by mouth daily for 2 months |

| Alendronate | Fosamax | 40 mg by mouth daily for 6 months |

| Zoledronate | Reclast | 5 mg IV once every 12 months |

| Salmon calcitonin | Miacalcin | 50-100 U subcutaneous injection daily for 6-18 months |

Surgical Treatment

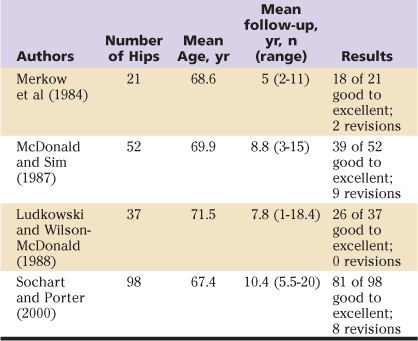

Both cemented and uncemented total hip arthroplasty have been used successfully to treat degenerative hip disease secondary to Paget’s disease, and good to excellent results have been reported for both. Nevertheless, no consensus has been reached regarding choice of implant or fixation technique. Direct comparison of available studies is difficult owing to confounding variables, results spanning two decades, small numbers of patients, differing implant designs, and evolving techniques. The degree of deformity, the amount of bone loss, and the need for osteotomy require implant selection and technique adjustment based on individual patient pathology. However, reported revision rates appear to be higher with the use of cemented implants. Results of available studies using cemented and uncemented implants are summarized in Tables 78-2 and 78-3. The use of hybrid THA in a Paget’s patient with severe proximal femoral involvement is demonstrated in Figures 78-2 and 78-3.

Table 78-2

Cemented Total Hip Arthroplasty for Paget’s Disease of the Hip

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree