Meniscus Resection

Emilio Lopez-Vidriero

Donald H. Johnson

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Pertinent History

The meniscus is commonly injured in sports, but can also occur as a sequela of age-related degeneration. In these cases, there may be no trauma, but more typically, patients report a twisting hyperflexion injury followed by pain. This acute episode may involve locking of the knee, with the development of moderate swelling over the first 24 hours. With recurrent episodes of pain and swelling, mechanical symptoms such as catching, popping, or locking are reported. The pain tends to localize along the joint line, especially with deep flexion and twisting motions.

It is important to establish symptoms of instability, because the menisci are a secondary restraint to anteroposterior translation, and certain tears can worsen in cases of an Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) deficient knee.

Physical Examination

The patient is examined for signs of an effusion, loss of quadriceps bulk, and decreased range of motion (ROM). Tenderness to palpation along either the medial or the lateral joint line is among the most significant sign of a meniscal tear (Fig. 55.1A), reported statistically at 74% with a positive predictive value of 50%. The collateral and cruciate ligaments must be assessed to rule out additional injury. With an ACL-deficient knee, the sensitivity of joint line tenderness has been shown to decrease to around 50%.

Special tests for assessing the meniscus, such as the McMurray, Steinmann, and Apley tests, can aid in the diagnosis, but the McMurray test is preferred because it is easy, fast, and reliable. Also, complementary knee tests may be done in the same position. The McMurray test is performed with the patient supine, the hip flexed to 90°, and the knee in forced maximal flexion. One hand grasps the heel, the knee is steadied, and the joint line palpated with the other hand. As the knee is slowly taken into extension, external rotation stress will test the medial meniscus, whereas internal rotation stress tests the lateral meniscus (Fig. 55.1B). As a mnemonic rule, the heel of the foot points toward the injured meniscus. The result of the test is considered positive when the patient feels pain in the appropriate joint line accompanied by a thud or click. When the clunk is present, the test has a sensitivity of 98% but, due to the fact that not always is possible to evoke the clunk, its specificity is only 15%.

In conclusion, the hallmarks of a meniscal tear are presence of an effusion, joint line tenderness, and positive McMurray test. When history and physical examination are used together, the overall sensitivity to diagnose a meniscal tear, confirmed with arthroscopy, is around 95% with a specificity of 88%.

Diagnostic Imaging

Evaluation of a meniscal tear should include routine AP and lateral X-rays of the knee. If degenerative changes are expected, standing views including a 45° flexion PA view should be performed to assess the degree of joint space narrowing. Assessing osteoarthritis is important to counsel the patient about expectations of success, because the degree of arthrosis before surgery predicts poorer postoperative results in the short and long term.

Although not clinically indicated in all patients, MRI is valuable in evaluating the full range of meniscal pathology. This includes the primary diagnosis of a meniscal tear, detection of a recurrent tear after resection or repair, and demonstration of associated injuries. MRI shows the relative locations of the tears and determines the presence of a meniscal tear with an accuracy of over 90%. It provides an accurate noninvasive technique for evaluating meniscal tears, especially when combined with pertinent history, and physical examination. This is particularly important when treating young adults, where tears can be completely asymptomatic.

Decision Making: Indications and Contraindications

Meniscectomy is indicated when the type of tear will not heal spontaneously, or in those cases where a repair is not possible. Although the technology is improving and the indications for repair are increasing, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is still indicated in 80% of the tears (Table 55.1).

Factors to consider when deciding whether to resect or to repair a meniscal tear are location of the tear, morphology, size, chronicity, and inherent patient factors.

In terms of location, tears in the white-white zone are resected because, according to Arnoczky, they have a low degree of vascularity and their chances of healing are very low. If the tear is in the white-red zone, the other abovementioned factors will inform the decision.

When morphology is taken into account, horizontal cleavage tears, radial lateral tears, and degenerative bucket handle tears of the meniscus are not usually considered repairable. Tears larger than 20 mm in size are normally resected.

Generally, tears are considered chronic after 8 to 12 weeks. Usually the meniscus becomes shredded, or degenerative with time, and is no longer suitable for repair.

In terms of the patients’ age, there may be less vascularity and cellularity in the older meniscus and thus less healing potential. The older patient often has a degenerative tear that is not repairable. There is no age limit to a meniscus repair, but most surgeons would favor resection over repair in patients over 40 to 50 years of age.

Patients with an acute ACL injury often have a small posterior flap tear of the lateral meniscus. Although there is some controversy, most people feel that this should simply be resected.

In the chronic unstable ACL-deficient knee, a meniscus tear should be resected, unless the ACL is reconstructed. Due to the abnormal kinematics of the ACL-deficient knee, the failure rate of meniscal repair in the unstable knee is much higher than the stable or reconstructed knee.

Table 55.1 Indications for meniscectomy. This table summarizes clinical situations where meniscectomy is preferred over repair | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Where patients are noncompliant with rehabilitation programs, resection is the better option.

Classification

Meniscus tears may be classified by the location of a tear relative to its blood supply and its vascular appearance. The peripheral and central surfaces can be clinically graded as white (relatively avascular) or red (vascular) at the time of arthroscopy. This classification is based on anatomic studies that have depicted a peripheral vascular zone. [Include a line drawing]

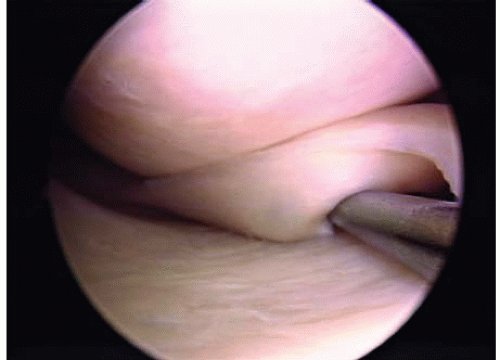

A red-red tear is defined as a peripheral capsular detachment, and it has the best prognosis for healing. Unfortunately, a significant portion of tears occur in the white-white zone, the central, avascular portion of the meniscus, and theoretically are unable to heal. The red-white (Fig. 55.2) are meniscal rim tears through the peripheral vascular zone of the meniscus. While the central portion of this tear exists in the avascular zone, theoretically, these lesions should have sufficient vascularity to heal by fibrovascular proliferation.

Conventional wisdom dictates that meniscal repairs be limited to the peripheral vascular area of the meniscus (i.e., the red-red and red-white tears). Both experimental and clinical evidence suggests that white-white tears are incapable of healing, even in the presence of surgical suturing, and has provided the rational for partial meniscectomy. In an effort to extend the zone of repair more peripherally, techniques such as the creation of vascular access channels by trephination, synovial abrasion, and the use of a fibrin clot have been developed.

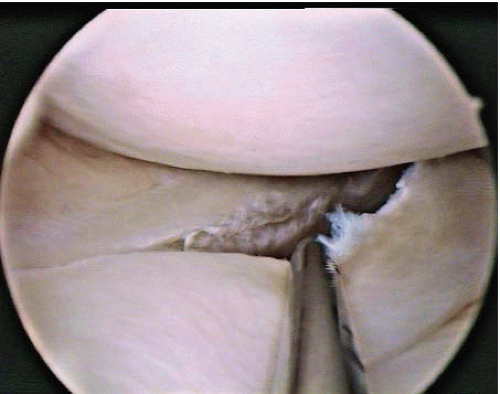

Meniscal tears can also be classified by their stability (Table 55.2). A tear is considered unstable when it is more than half the length of the meniscus and subluxes under the femoral condyle when probed with a hook (Fig. 55.3). This concept is especially important in deciding treatment options: leave alone, trephinate, resect, or repair.

Table 55.2 Criteria of stability defined arthroscopically using the probe | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

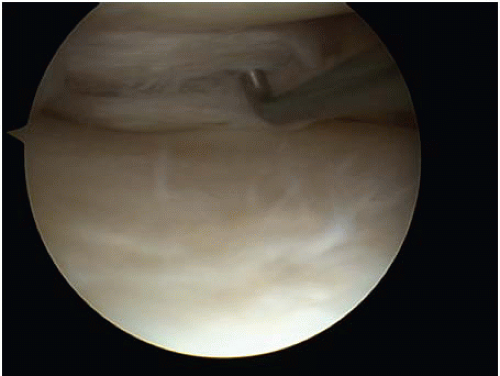

FIGURE 55.3. Unstable longitudinal vertical tear. Note how it subluxes under the femoral condyle when probed. |

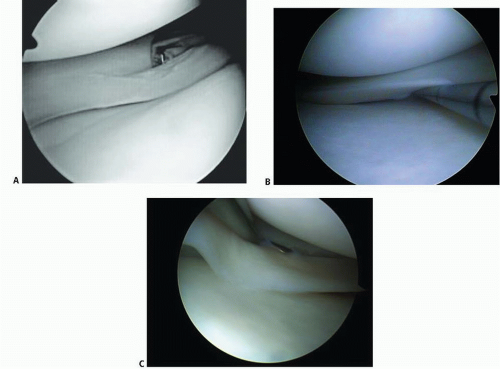

Stable tears, which occur particularly in the posterior aspect of the meniscus and which do not subluxate into the joint, may be left alone (Fig. 55.4A-C).

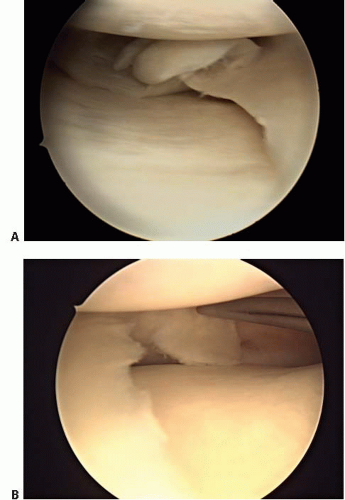

Tears can be described according to their morphology and based on their configuration. Under these criteria, tears can be vertical or horizontal, depending on whether the line of the lesion goes from superior to inferior (vertical) (Figs. 55.3 and 55.4), or from inside to outside (horizontal), and commonly called “open book” or “fish mouth” (Fig. 55.5). Moreover, tears can be described as longitudinal (Figs. 55.3 and 55.4) if the pattern is from anterior to posterior, or transverse, and are also called radial or “parrot beak” (Fig. 55.6). Combinations of these four basic patterns make up the others types of tears: the oblique, being vertical and radial or the so-called bucket handle, which is a vertical-longitudinal tear that is unstable, and subluxes completely under the condyle (Figs. 55.3 and 55.7A-C). Lastly, the complex tear is a combination of all, usually in the degenerative setting, and located in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (Fig. 55.8).

Longitudinal-vertical tears usually occur in younger patients, in association with an ACL tear, and more frequently in the medial meniscus because it is less mobile. Oblique tears tend to appear between the medial and the posterior third of the meniscus. They may cause mechanical symptoms of entrapment and pain, due to the tension on the meniscus-capsule junction.

FIGURE 55.5. Horizontal degenerative tear. Note how it opens with the use of the probe. Some of these tears may reach the meniscocapsular junction. |

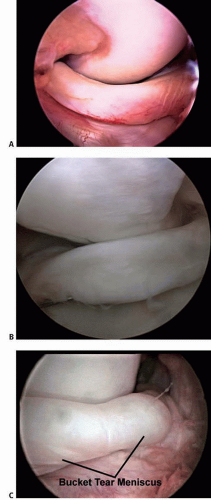

FIGURE 55.7. A: Bucket handle tear dislocated into the intercondylar notch. This meniscus is torn in the red-white zone. Note the vascular supply to the dislocated fragment. Some of these tears are amenable to repair. B: Bucket handle tear that dislocates into the intercondylar notch when probed. Note the chondral lesion on the condyle. C: Irreducible bucket handle tear.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|