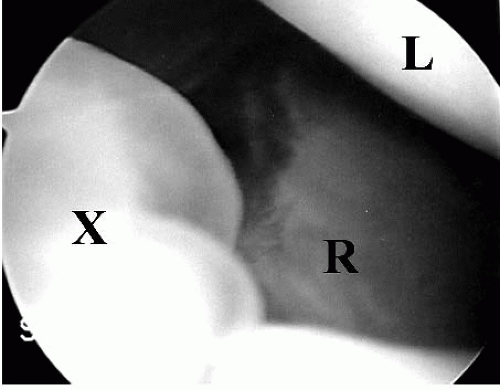

Cystic stalks, which may appear to be pedunculated or sessile protuberances, may be viewed in the radiocarpal joint at the interval between the dorsal scapholunate ligament and the capsule inflection that separates the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints (

Fig. 41.1). In reviewing the current literature, the exact roles of intra-articular cystic stalks are somewhat ambiguous. According to previous reports, although not specifically stated, it has been implied that the identification and surgical excision of the stalk is paramount when using standard arthroscopic technique for ganglion excision. However, the presence of this important structure has been variable in the literature. Osterman and Raphael (

1) identified a stalk in twothirds of their patients undergoing arthroscopic ganglion excision. Despite the fact that one-third of their patients had no identifiable stalk, ganglions were successfully excised with no recurrences. Other studies have reported a stalk incidence as low as 10% (

2,

3 and

4). Despite vastly different reports on stalk identification, the importance of such pathology must be questioned. Rather than a cystic stalk, Edwards and Johansen (

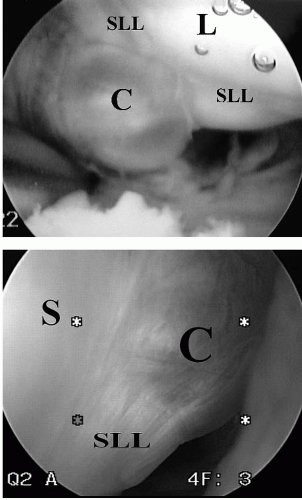

4) described intra-articular cystic material and redundant capsular tissue in the vast majority of their patients with ganglion cysts (

Fig. 41.2). This finding, which was more consistently evident, was the focus of their resection, rather than the stalk.

The intra-articular limitations of arthroscopic viewing may explain the paucity of stalk identification. The radiocarpal and midcarpal joints are separated by the extrinsic capsular ligaments. At this separation, the dorsal capsular reflection is adherent to the interosseous scapholunate ligament. It is possible that a ganglion stalk travels toward the scapholunate ligament within the substance of the dorsal capsular reflection, rather than through the radiocarpal or midcarpal spaces, and the stalk may never be visualized by arthroscopy. Certain observations during arthroscopic resections may support this theory. On several occasions, extravasations of cystic fluid can be noted during the debridement of the dorsal capsular reflection between the radiocarpal and the midcarpal joints when stalks had not been visualized in either compartment. In other words, the stalk may have been hidden within the dorsal capsular extrinsic ligaments.