Chapter 86 Meniscal Disorders

Meniscal Tears

Meniscal tears are being seen with increasing frequency in the pediatric population.9 Potential causes of this include a rise in organized sports participation in younger children, an improved awareness of this diagnosis among common practitioners, and wider availability and improved quality of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).33

Anatomy and Classification

Pediatric meniscal tears are believed to have a greater healing potential as compared with adult tears.10 This may be in part to the result of the vascularity of the developing meniscus. The meniscus is completely vascular at birth, and its vascularity gradually diminishes over time, resembling the adult meniscus by age 10.21 The peripheral 25% to 30% of the adult meniscus has direct vascular supply from the perimeniscal capillary plexus and so is termed the red-red zone. This area is thought to have the greatest potential for repair. The remainder of the meniscus obtains its nutrition through synovial diffusion with the middle third, termed the red-white zone, and the central third, termed the white-white zone to emphasize diminishing vascular supply.

Other factors may also contribute to the healing potential of pediatric and adolescent meniscal tears. Pediatric meniscal tears usually occur following a specific injury to a previously normal meniscus. Simple nondegenerative tear patterns are most common and include longitudinal and bucket handle tears in the red-red zone.14 Degenerative tear patterns such as parrot beak, horizontal cleavage, and complex tears are more often seen in the adult population and have lower healing potential. Additionally, many pediatric meniscal injuries occur in the setting of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears.56 The highest healing rates for meniscal repair have traditionally been seen in the setting of ACL reconstruction.

Diagnosis

Meniscal tears in children younger than 10 years generally occur in the setting of a discoid meniscus. Nondiscoid tears most commonly occur in the adolescent age group following a twisting knee injury during sports activities. Children often present with knee pain and swelling. Mechanical symptoms such as locking or catching suggest meniscal tear instability. A locked knee (unable to be fully extended or flexed) is highly suggestive of a displaced bucket handle meniscal tear. In these cases, displaced meniscal tissue occupies the intercondylar notch area to block motion. A hemarthrosis is a strong indicator of potential meniscal pathology. In one report, meniscal tears were identified in approximately 45% of children ages 7 to 18 years who presented with an acute knee hemarthrosis.56 In this series, the medial meniscus was more commonly torn (70% to 88%) and a concurrent ACL tear was noted in 36% of the adolescents.

On physical examination, a knee effusion is often accompanied by joint line tenderness. Range of motion should be carefully assessed to identify mechanical blocks to motion. Provocative physical examination maneuvers on children may be difficult and limited by pain and apprehension. The traditional McMurray test for meniscal pathology in adults requires 90 degrees of knee flexion, which may be uncomfortable for children following a knee injury. The test has been modified for children: the knee is flexed to 30 to 40 degrees and a rotational varus or valgus stress is placed on the knee.9,11 Joint line pain following this maneuver is indicative of meniscal pathology. When performed by an experienced examiner, the physical examination can be used to diagnose both medial (62% sensitivity, 80% specificity) and lateral (50% sensitivity, 89% specificity) meniscal tears in children reliably.30 Other potential diagnoses must be considered in this population, including patellar dislocation, osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), osteochondral injury, and plica syndrome. The ipsilateral hip should be assessed because knee pain may be indicative of hip pathology (e.g., slipped capital femoral epiphysis) in this age group.

A meticulous ligamentous examination of the knee is necessary for children with suspected meniscal tears. Concurrent injuries such as ACL tears are common.56 The Lachman test is reliable in the pediatric population for the diagnosis of ACL insufficiency but the test findings must be compared with those of the contralateral knee because normal tibial translation is increased in younger patients.16 Knee radiographs are standard following knee injuries in children. A complete radiographic series in children includes an anteroposterior (AP), lateral, intercondylar notch (tunnel), and Merchant (sunrise) views. Tunnel views are helpful to identify OCD lesions located posteriorly on the femoral condyles whereas sunrise views can show patellar subluxation or osteochondral loose bodies indicative of patellar dislocation.

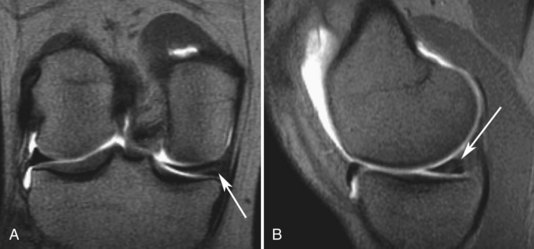

(MRI, when used appropriately, can aid in the diagnosis of meniscal pathology. In the proper clinical setting, MRI findings can support a presumptive diagnosis of meniscal pathology in children. Overuse of MRI in children, however, has its drawbacks. A high rate of false-positive MRI findings has been noted in the pediatric population.40 The increased vascularity of the pediatric meniscus causes intrameniscal signal change, which can be misinterpreted as a meniscal tear (Fig. 86-1). MRI has lower sensitivity and specificity when used to evaluate meniscal pathology in children compared with adults and in younger children compared with older children.56 MRI sensitivity (61.7%) and specificity (90.2%) for the diagnosis of meniscal tears in children younger than 12 years has been reported and compared unfavorably with children aged 12 to 16 years old (sensitivity 78.2%; specificity 95.5%).30 Advances in MRI have improved these percentages in the adolescent age group.38

Treatment

Asymptomatic meniscal tears noted incidentally on MRI can be observed over time for healing. Small symptomatic meniscal tears noted on physical examination or MRI scans may be initially treated with a trial of conservative management but persistent symptoms warrant surgical intervention. Large tears should be addressed surgically in a prompt fashion because higher healing rates have been reported when the tear is repaired within 3 months of the injury.60 Meniscal tears identified during arthroscopy should be assessed for stability. Small tears (<10 mm) that are stable (manually displaceable less than 3 mm) may heal without repair. Meniscal trephination and synovial rasping are commonly used techniques to stimulate bleeding near the tear site.

In most cases, arthroscopic meniscal repair is favored over partial or total meniscectomy in children. Most pediatric tear patterns are amenable to repair. Removal of part or all of the meniscus may accelerate degenerative changes in the knee.41 Contact forces in the knee increase significantly following partial meniscectomy in proportion to the amount of meniscal tissue removed.36 Removal of a small bucket handle medial meniscal tear increases contact stresses by 65% and débridement of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus increases contact stresses to near-total meniscectomy.7,17 Total meniscectomy increases contact stresses by 235% and should be avoided in the pediatric population. One group reported that at 5-year follow-up after partial or total meniscectomy in 20 children, mean age 15 years, 75% of patients continued to have symptoms, 80% had radiographic changes consistent with early osteoarthritis, and 60% were dissatisfied with their results.39 A recent review has noted that 50% of patients who underwent total meniscectomy had radiographic changes, symptoms, and functional loss consistent with osteoarthritis at 10- to 20-year follow-up.37 Unfortunately, no studies to date have demonstrated whether meniscal preservation through repair lowers the incidence of early osteoarthritis in this young and active population.

Fortunately, most pediatric meniscal tears are amenable to repair. Longitudinal peripheral tears in the red-red zone are the most common tear type (50% to 90%) and are ideal tears to repair.17 Other repairable tear types include bucket handle tears, meniscal root tears, and most tears that extend into the red-red or red-white zones. Many meniscal repairs in children are done in the setting of ACL reconstruction, which increases the potential for success.35 Complex, degenerative, adult-type meniscal tear patterns, such as horizontal cleavage tears and radial tears, are less commonly seen in the pediatric population and may reflect a genetic or structural weakness of meniscal tissue.33 These tears are generally treated with partial meniscectomy, with an attempt to preserve as much meniscal tissue as possible.

Arthroscopic techniques for meniscal repair can be divided into three groups—inside-out, outside-in, and all-inside repair. For all techniques, the tear is first identified and probed to evaluated size, location, tear pattern, and instability. Repairable tears are then reduced and the tear site is prepared for repair through rasping of the nearby synovium to create a bleeding surface for repair. Inside-out arthroscopic techniques have traditionally been the gold standard method of repair for most midbody and posterior horn tears. This technique relies on the use of double-armed absorbable or nonabsorbable repair sutures linking long flexible needles. The flexible needles are placed through curved cannulas and across the meniscal tear in a horizontal or vertical mattress fashion. The sutures are spaced approximately 3 to 5 mm apart and must be tied down to the capsule through a separate incision (Fig. 86-2).20 An open incision may be necessary to protect posterior neurovascular structures for inside-out repair of posterior horn tears. Outside-in repair is a similar technique used mostly for anterior horn tears that relies on sutures fed through spinal needles percutaneously placed across the tear site. After passing through the tear, the sutures are retrieved and tied down to the capsule anteriorly.

Recently, arthroscopic all-inside meniscal repair techniques have gained in popularity. These techniques rely on newer generation implants that are suture-based, flexible, and low profile and provide secure fixation across the tear site while minimizing risk of adjacent chondral injury (Fig. 86-3). These implants rely on capsular penetration for deployment during repair of tears. In younger children and smaller knees, the posterior neurovascular structures lie near the posterior capsule, which may preclude the use of these implants for posterior horn tears. In these cases, a standard inside-out repair with protection of the posterior neurovascular structures is safest.

Outcome

Prior studies have published promising results on meniscal repair in children as part of a larger cohort of adult patients.13,58 There is a paucity of data on success rates of meniscal repairs in an exclusively adolescent population. In the first published report, 26 patients, mean age 15.3 years (range, 11 to 17 years), underwent 29 meniscal repairs (12 medial and 17 lateral), with 15 of the patients (58%) undergoing simultaneous ACL reconstruction.42 All repairs were performed arthroscopically, 25 with an inside-out technique and 4 with an all-inside technique. At mean 5-year follow-up, no meniscal symptoms were noted, all meniscal repairs were believed to have healed, and 27 of 29 patients returned to preinjury level sports. Another series reported results on 71 children and adolescents, mean age 16 years (range, 9 to 19 years), following repair of complex meniscal tears extending into the central avascular region.1 At a mean 51-month follow-up, 53 of 71 patients (75%) were deemed clinically healed. Notably, an 87% healing rate (39 of 45 patients) was noted in patients who were simultaneously undergoing ACL reconstruction.45

A retrospective case series of 45 isolated meniscal repairs in children, mean age 16 years (range, 10 to 18 years), reported clinical success in 80% of simple tears, 68% of displaced bucket handle tears, and 13% of complex tears at a mean follow-up of 5.8 years.65 Of these, 17 repairs (38%) failed at a mean time of 17 months (range, 3 to 61 months) and required reoperation. Failure was associated with a rim width of 3 to 6 mm from the meniscosynovial junction, suggesting a tear location outside the red-red zone. The same group later reported improved meniscal repair results in the setting of ACL reconstruction. In 96 children, mean age 16 years (range, 13 to 18 years), clinical success was 84% for simple tears, 59% for displaced bucket handle tears, and 57% for complex tears. Another group included adolescents in a larger adult series and reported an 82% healing rate (based on second-look arthroscopic evaluation) for bucket handle meniscal repairs done in the setting of ACL reconstruction.14

Complications of meniscal repair in children are rare but can include neurovascular injury, arthrofibrosis, complex regional pain syndrome, and chondral injury from a protruding implant. In the studies noted, only two cases of arthrofibrosis and one painful neuroma of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve following inside-out repair were reported.42 Although success rates following meniscal repair in the adolescent population are encouraging, long-term data are lacking and it remains to be seen whether meniscal preservation through repair will translate into lower rates of early osteoarthritis for these young active patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree