Fig. 1.1

Cross-sectional view of meniscus demonstrating orientations of fibers. (1) Superficial mesh layer, (2) lamellar network, and (3) circumferential fibers. Arrows indicate radially oriented fibers. (Reprinted with permission from Springer: Petersen, W. and B. Tillmann, Collagenous fibril texture of the human knee joint menisci. Anat Embryol (Berl), 1998. 197(4): p. 317–24)

The composition of the extracellular matrix of meniscus is generally accepted to be roughly 70 % water and 30 % dry weight in the mature knee [6]. In the young knee, water content is much higher until the composition of the collagen and proteoglycans increases to levels typically seen in adults [16]. The dry weight portion can be divided into collagen, noncollagenous proteins, and proteoglycans. The predominate collagen is type I collagen with varying degrees of type II, II, V, and VI collagens [6]. Elastin is an integral noncollagenous protein that serves to aid in the overall structure and stability of the menisci and comprises 0.6 % of the dry weight [6, 17]. Proteoglycans are formed by a protein core to which one or more glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains are attached. In comparison to articular cartilage found elsewhere, the proteoglycan content in the meniscus is significantly less among the same species [18, 19]. The predominate GAGs are chondroitin 6-sulfate, chondroitin 4-sulfate, keratin sulfate, and dermatan sulfate [6].

Macroanatomy

Medial Meniscus

The medial meniscus has a C-shape appearance and covers approximately 50 % of the medial tibial plateau. The size of the medial meniscus approximates 4.4 cm in length and 3.1 cm in width. Meniscal dimensions have been strongly correlated to a patient’s gender, height, and weight and are important to take into account when considering meniscal transplantation [20]. The posterior horn is larger than the anterior horn in the anteroposterior dimension. The medial meniscus has multiple attachments within the medial compartment. It is attached at the anterior and posterior horns through bony attachments and along the periphery to the joint capsule. The anterior attachment has been shown to have multiple variations with four distinct types currently described [21]. Posteriorly, the attachment is anterior to the attachment of the posterior cruciate ligament. The coronary ligament attaches the inferior aspect of the meniscus to the tibia [22]. Unique to the medial meniscus is its attachment to the deep fibers of the medial collateral ligament.

The medial meniscus can translate approximately 5 mm in the anterior-posterior plane which allows for adequate femoral rollback during knee flexion [23, 24]. Because of the relatively firm attachments to surrounding soft tissue and bony structures, the medial meniscus provides anteroposterior stability to the knee, which is most evident in cases of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) deficiency. The posterior horn of the medial meniscus acts as a wedge to block anterior translation and thus is an important agonist to the ACL. In the presence of ACL injury, the posterior horn of the medial meniscus experiences large stresses that can lead to attritional tears over time. Such tears can nullify the hoop forces that contribute to the shock dissipation characteristics of the meniscus. In addition, a combined ACL deficiency and medial meniscectomy can lead to an average 58 % increase in anterior tibial translation [25].

Lateral Meniscus

The lateral meniscus has a more circular or ovoid appearance and covers approximately 70 % of the lateral tibial plateau. Dimensions of the lateral meniscus approximate 3.6 cm in length and 2.9 cm in width. Similar to the medial meniscus, variations in sizing is largely correlated with gender, height, and weight. The anterior and posterior attachments of the lateral meniscus are much closer together than that of the medial meniscus (see Fig. 1.2). Anteriorly, the lateral meniscus attaches adjacent to the anterior cruciate ligament. Posteriorly, the attachment is behind the intercondylar eminence anterior to the attachment of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. In addition to the bony attachments of the anterior and posterior horns are the meniscofemoral ligaments and the popliteomeniscal fasciculi. The ligament of Wrisberg passes posterior to the PCL and attaches to the femur, while the ligament of Humphrey passes anterior to the PCL. In some discoid variants, the bony attachment of the posterior horn is completely absent, and the ligament of Wrisberg becomes the primary posterior stabilizer. The popliteomeniscal fasciculi connect the lateral meniscus to the popliteus tendon and joint capsule, adding to the stability of the lateral meniscus [26]. Overall, the lateral meniscus is more loosely affixed to the lateral compartment than the medial meniscus is within the medial compartment. The lateral meniscus can translate approximately 11 mm during normal knee kinematics [24]. This increased mobility allows the increased tibiofemoral excursion seen in the lateral compartment.

Fig. 1.2

Meniscal Anatomy and relationship to important structures of the knee joint. (Reprinted with permission from: Pagnani MJ, Warren RF, Arnoczky SP, Wickiewicz TL: Anatomy of the knee, in Nicholas JA, Hershman EB, eds: The Lower Extremity and Spine in Sports Medicine, 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO, Mosby, 1995, pp 581–614)

Discoid Meniscus Variants

Variants of the anatomic appearance of the menisci are much more common in the lateral meniscus with a reported incidence between 1.5 and 16.6 %, and of these, 5–20 % occur bilaterally [27–34]. The Watanabe classification is used to describe discoid variants of the lateral meniscus. Three distinct types exist: (a) incomplete, (b) complete, and (c) Wrisberg variant (see Fig. 1.3). Discoid menisci are thicker, often lack a consolidated matrix, lack the normal tapered central contour seen in normal menisci, and, in the case of the Wrisberg variant, lack normal bony attachments, predisposing them to failure. Majority of the time, however, discoid variants are asymptomatic and are incidental findings.

Fig. 1.3

Watanabe’s classification of discoid meniscus. (Reprinted with permission from Springer: Atay OA, Yılgör İÇ, Doral MN. Lateral Meniscal Variations and Treatment Strategies. In: Doral MN, editor. Sports Injuries. Heidelberg. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg; 2012)

Meniscomeniscal Ligaments

In addition to the tibial, meniscofemoral, and capsular attachments listed previously, there also variable attachments that connect the two menisci together. There are four normal meniscomeniscal attachments that have been described: the anterior and posterior transverse meniscal ligaments and the medial and lateral oblique meniscomeniscal ligaments. The most prevalent by far of these is the anterior transverse meniscal ligament which is present in roughly 58 % of patients. The orientation of the fibers is such that the anterior horn of the medial meniscus is attached to the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus and three variants have been described (see Fig. 1.4) [35]. The overall significance of these attachments is debated, with some investigators ascribing a significant stabilizing role to the anterior horn of the medial meniscus. However, it is important to keep these in mind when evaluating MRI’s which can easily be misinterpreted as an anterior horn meniscal tear [36].

Fig. 1.4

Variations in the attachment of the anterior transverse meniscal ligament. (a) Type I attachments to anterior horn of medial meniscus and anterior margin of lateral meniscus. (b) Type II attachments to the medial aspect of the anterior horn of the medial meniscus and the joint capsule anterior to the lateral meniscus. (c) Type III attachments to the joint capsule anterior to both the medial and lateral meniscus, no direct meniscal attachments. (Reprinted from [35] with permission from SAGE Publications)

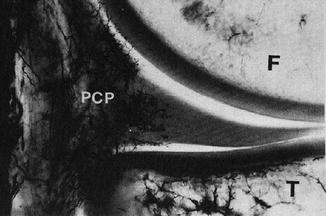

Vascular Supply

The main vascular supply to the meniscus comes primarily from the superior and inferior geniculate arteries; the middle geniculate supplies a portion of the anterior and posterior horns. At birth the entire meniscus is highly vascular [5]. This changes rather rapidly with normal development, and by the age of 9 months, the inner one-third becomes avascular. By the age of 10, the vascular supply to the meniscus approximates that of the adult meniscus. The superior and inferior geniculate arteries form a perimeniscal network of capillaries that infiltrate the periphery of the meniscus. This plexus of capillaries supplies 10–30 % of the medial meniscus and 10–25 % of the lateral meniscus [37] (see Fig. 1.5). A small area immediately adjacent to the popliteus is completely avascular [37]. In addition to the vascular supply, a small amount of nutrients are supplied by diffusion of synovial fluid [23].