Chapter 43 Medical Human Sexuality

Overview

Models of Human Sexual Response

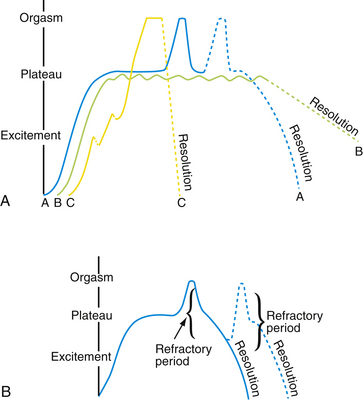

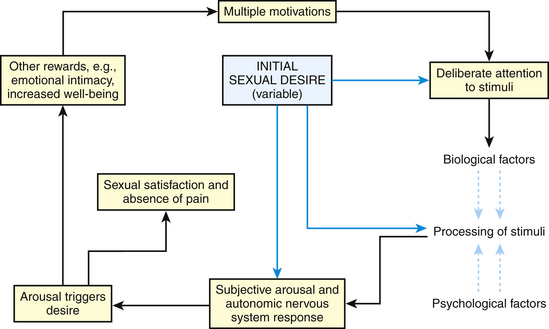

Masters and Johnson first described the physiology of “human sexual response cycle” in 1966. Based on the physical components of sexual functioning, they described four phases of the sexual response cycle: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution (Fig. 43-1). Helen Singer Kaplan subsequently described a more subjective, psychologically oriented sexual responsiveness model with three phases: desire, excitement, and orgasm. Recently, however, nonlinear alternative models have been suggested, especially for women’s sexual response (Basson and Schultz, 2007) (Fig. 43-2). In certain settings, men may have similar nonlinear sexual responses. Response phases establish a framework to discuss sexual dysfunction.

Initial Evaluation of Sexual Problems

The sexual health interview may be approached with a screening or abbreviated method, followed by in-depth questioning, if necessary (Nusbaum and Hamilton, 2002) (Box 43-1). The answers on the detailed sexual history then direct the physical examination and appropriate laboratory testing. A physician may open the sexual history questioning with an inclusion technique: “Sexual health is important to overall health, therefore, I ask all my patients about it. I’m going to ask you a few questions on sexual matters now.” The clinician can use normalization or universalization techniques. In normalization the clinician introduces emotionally laden or difficult subjects by implying these experiences are quite prevalent: “Many people have been sexually abused or molested as children. Did you have any experiences like that when you were young?” Universalization phrases questions as if everyone has done everything, making an affirmative answer easier for sensitive questions. For example, patients may be asked “How often do you masturbate?” instead of “Do you masturbate?” The clinician should also reassure the patient about physician-patient confidentiality.

Box 43-1 Questions for a Detailed Sexual History

From Nusbaum MRH, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:1705-1712.HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; IV, intravenous.

Jack Annon in 1976 proposed the PLISSIT model to approach sexual concerns: Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Treatment (Box 43-2). The clinician can alternatively use the ALLOW acronym: Ask, Legitimize, Limitations, Open up, and Work together (Hatzichristou et al., 2004), as discussed next.

Box 43-2 PLISSIT Model for Approaching Sexual Problems

Modified from Annon JS. The Behavioral Treatment of Sexual Problems. Honolulu, Enabling System, 1974-1975.

Limitations. The patient’s knowledge may have limitations, and patient education may address the patient’s perceived sexual dysfunction. For example, an older man with longer time between erections may not know the refractory period normally increases with age. Patient education and reassurance may eliminate his perceived “sexual dysfunction.” Physicians should recognize their own limitations and, if necessary, refer a patient to the appropriate specialist for further evaluation and treatment of a sexual dysfunction.

Open up, for further discussion and evaluation. A detailed sexual history may be needed to evaluate fully a patient’s sexual concern (see Box 43-1). If the time constraints limit the current visit, the physician should offer the patient a future follow-up visit.

Work together, to develop a treatment plan. In some cases, simply following the previous four steps may be therapeutic. Many clinical cases can be managed with brief education or limited advice, such as discussing normal physiologic sexual changes with aging or recommending books or products (e.g., water-based lubricant for vaginal dryness). When a referral has been made, scheduled follow-up supports the patient during the process and helps address administrative or adherence issues. Counseling may be extremely important, and the physician should research local resources. The American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors, and Therapists (AASECT) may be contacted for referral information (http://www.aasect.org).

Female Sexual Dysfunction

Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder

For women, low sexual drive is the most frequently reported sexual problem. Four in 10 women state they have low sexual drive. The lack of sexual desire may not be distressing for all women, with “distress” prevalence ranging in studies from 23% to 61% (Lindau et al., 2007; Shifren et al., 2008). Hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) may be general (a general lack of sexual desire), situational (previously present sexual desire is now absent), acquired (beginning after a period of normal sexual function), or lifelong (persistent no or low sexual desire). The cyclic model of sexual functioning postulates that arousal, not desire, may be the initial trigger for a woman’s sexual encounter. Recently, therefore, experts suggest defining HSDD as a recurrent, consistent lack of ability to experience any desire or arousal (Basson et al., 2004). A brief questionnaire can be helpful to screen patients for HSDD (see eTable 43-1 online).

Female Orgasmic Disorder

In both primary and secondary orgasmic dysfunction, it is important to ask about past or current experiences of violence, victimization. and abuse. Social factors also affect a woman’s experience of orgasm. Women taught negative messages regarding sexuality or with strict religious or cultural prohibitions on sexual attraction and thoughts may experience orgasmic difficulty, even if the specified conditions for sexual behavior (e.g., marriage) have been fulfilled. Women who were born later in the 20th century are more likely to experience orgasm than those born earlier, likely reflecting social changes. Secondary inhibited orgasm can be caused by other medical illnesses and contributing contextual factors.

Sexual Pain Disorders

Vaginismus

Dyspareunia

Treatment of physiologic dyspareunia caused by atrophic vaginitis may require vaginal estrogen. Vaginal infections must be diagnosed and treated. For poor lubrication, supplemental water-based lubrication may be sufficient. Deep dyspareunia is often caused by overvigorous penetration or excess cervical pressure and may respond to brief educational interventions. Many people do not realize that penises and vaginas vary in length, and the vagina may not stretch to accommodate full penile engulfment. Changing position to allow the woman to control the amount of cervical pressure may ameliorate the dyspareunia. Referral for sex therapy for the couple may prove helpful. In some cases, the patient may be able to bring about change in the sexual relationship with sufficient information and assertiveness. If dyspareunia is the result of deliberate carelessness or abuse by the partner, ending the relationship is usually the only reasonable option.

Male Sexual Dysfunction

Erectile Dysfunction

Evaluation

Clinicians should carefully evaluate the patient’s complaint of ED, because some men consider premature ejaculation as “erectile dysfunction.” After obtaining the pertinent history, the clinician should carefully review the patient’s past medical history. Because penile erection depends on intact vasculature, the medical history is similar to one assessing cardiovascular risk factors: “What is bad for the heart is bad for the penis.” Several common classes of medicines can cause sexual dysfunctions (Box 43-3). The social history should include the patient’s smoking, alcohol, and marijuana use, and the patient’s important social and sexual relationships. The physician should also assess psychological factors such as depression and anxiety.