Massive Cuff Repairs: A Rational Approach to Repairs

Jeffrey S. Abrams

KEY POINTS

Massive rotator cuff tears include three or more of the rotator cuff tendons.

Pathology anteriorly, superiorly, and posteriorly can be visualized by placing the arthroscope in multiple portals.

Biceps tendon pathology is a common source of pain in shoulders with large and massive rotator cuff tears. Biceps tenotomy or tenodesis may be helpful in reducing the pain.

Patient selection is a combination of factors including age, chronicity of the tear, radiographic imaging, and medical and physical comorbidities. Surgeons need to consider not only shoulders to be repaired but also shoulders that will heal.

Surgical tear patterns are either based anteriorly surrounding the subscapularis-supraspinatus interval or posteriorly at the supraspinatus-infraspinatus interval. Recognition of patterns is helpful in creating a low-tension repair.

Articular and bursal releases may include capsulotomy, coracohumeral releases, bursectomy, modified decompression, coracoid arch releases, and interval releases.

After diagnostic arthroscopy, repairs begin anteriorly due to spatial limitations. Following subscapularis repair, anterior releases from a bursal perspective can be performed.

Delaminations and mid-tendon tears need to be recognized to complete full-thickness repairs. Since the tendency is to create convergence of the cuff from multiple directions, anchor spreading is a preferred construct to stabilize the repair.

The massive rotator cuff tear includes at least three tendons. Many surgeons have incorrectly referred to the massive tear as one that is irreparable. Today, the massive rotator cuff tear has many surgical options, including arthroscopic repair (1, 2 and 3). It is critical that the treating physician carefully evaluate the characteristics of the muscle, tear pattern, patient’s comorbidities, and degree of disability to determine the best method of management. The etiology of a massive tear may be trauma or an extension of an existing medium-sized tear following a specific event. These tears may be found at times in an older population with chronic changes noted on imaging studies. With improved imaging studies, rotator cuff tears are being diagnosed prior to significant muscular changes following trauma. This may present an opportunity to treat and repair symptomatic shoulders prior to permanent changes developing within the muscles and tendons. The possibility of successful healing and a “watertight” closure is best in the younger individual with minor changes to the detached cuff tendons. Delays in treatment may lead to tear extension and retraction, muscular atrophy, fatty changes within the muscles, superior migration of the humeral head, decreased tendon vascularity, and tuberosity osteopenia—all of which can impact the ability of healing.

Tear pattern recognition is important to understand how some small and medium tears can extend into a massive tear. Most rotator cuff tears begin along the anterior edge of the supraspinatus tendon. Tear extension is most common in a posterior direction, which eventually causes disruption of the entire supraspinatus and extends through the overlapping infraspinatus insertion. Some tears will also extend anteriorly across the rotator cuff interval to include the subscapularis. The massive cuff tear pattern is most often a crescent-shaped tear. The medial extension along the intervals, either anteriorly into the subscapularis or posteriorly into the infraspinatus, may create delaminations and a multilayered tear. In order to consider a repair that has minimal tension, these complex tear patterns need to be recognized and anatomically addressed when possible. The rotator interval may be included in this tear pattern, and disruption of the biceps pulley system is common (4). Treatment of biceps tears or instability may need to be included in the treatment of the massive rotator cuff tear.

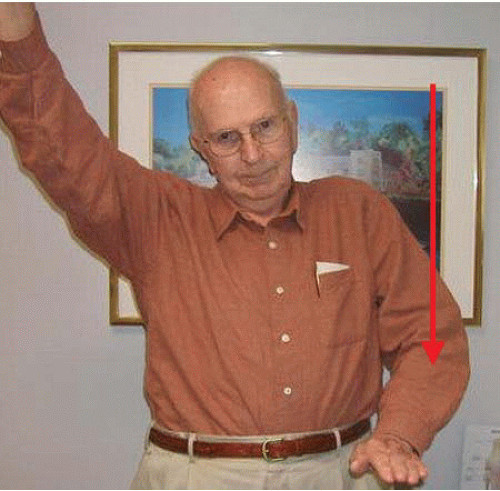

Patients with a massive rotator cuff tear may exhibit a number of complaints ranging from resting pain to complete loss of function (Fig. 11.1). One role of the rotator cuff is to stabilize the glenohumeral articulation during functional elevation created by the deltoid. As the tear extends, certain shoulders are unable to compress the humeral head into the glenoid. This is rarely found with a

single tendon tear and is more likely attributed to tears that include the superior portion of the subscapularis and the majority of the infraspinatus (5). This condition has been compared with a boutonniere deficiency seen with extensor capsule disruption of a finger. The remaining tendons sublux inferior to the axis of the joint creating an adductor force during an attempt of arm abduction. This results in a shrug sign. Over time, this dynamic loss may evolve into a fixed deformity reducing the humeral head acromion interval on a sitting or standing radiograph (Fig. 11.2).

single tendon tear and is more likely attributed to tears that include the superior portion of the subscapularis and the majority of the infraspinatus (5). This condition has been compared with a boutonniere deficiency seen with extensor capsule disruption of a finger. The remaining tendons sublux inferior to the axis of the joint creating an adductor force during an attempt of arm abduction. This results in a shrug sign. Over time, this dynamic loss may evolve into a fixed deformity reducing the humeral head acromion interval on a sitting or standing radiograph (Fig. 11.2).

An arthroscopic evaluation of a massive rotator cuff tear allows a thorough examination without deltoid detachment or retraction. There have been studies that recommend an open approach to a large and massive tear; however, these have been challenged by newer arthroscopic techniques, which mobilize tears and create secure repairs to the tuberosities (6,7). Advantages of arthroscopy include (1) reduced risk of infection, (2) reduced risk of postoperative stiffness, (3) reduced risk of deltoid injury, and (4) reduced morbidity during the early postoperative period.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

History

The key features obtained in a history include the patient’s symptomatic problems and whether there was a traumatic onset. Treatment for pain has the best chance of successful results. Trauma suggests a recent onset. Patients who have had prior treatment including cortisone injections and therapy may have had a chronic cuff tear that was exacerbated with trauma. The development of chronic muscle and tendon changes include decreased vascularity to the damaged structures.

FIGURE 11.2. Standing radiograph demonstrating reduction of the acromiohumeral interval and chronic changes to the greater tuberosity and acromion. |

Select patients may present with the acute onset of weakness following a minor traumatic event. These patients may have had a well-compensated tear that was injured further. Details regarding the change in shoulder function are important to clarify. Although surgery for weakness has met with mixed results, acute repair of tear extensions and release of neurologic entrapment may return a patient’s ability to elevate their arm (8,9).

Physical Exam

Observe the shoulder in a gown that does not cover the scapula and the deltoid. Look for significant degrees of atrophy in the supraspinatus, the infraspinatus, and the generalized shoulder musculature. Ask the patient to lift both arms to make comparisons with ranges of motion and whether movement is initiated by the glenohumeral joint or by raising the scapula. Measure flexion, external rotation with the elbow at the side, and internal rotation behind the back. Gentle strength testing can be performed by using the belly-press sign (subscapularis) and resistance against external rotation (infraspinatus and teres minor). The distal neurovascular examination may indicate whether a cervical problem may play a role in creating the shoulder symptoms.

Local tenderness can be elicited by direct pressure over the tuberosities and bicipital groove. Many patients will complain of tenderness along the margins of the tear posteriorly and anteriorly. Identify any associated symptoms including biceps pathology.

Imaging

In order to optimize patient selection, accurate imaging studies are important. Plain radiographs include three views. The anteroposterior view of the glenohumeral joint should be performed in an upright patient to identify “fixed” superior migration. A measurement of the acromiohumeral distance can be made. The literature suggests that 11 mm is

normal and that less than 6 mm may suggest an irreparable tear and is suggestive of the need for surgical repair (10). Degenerative joint changes can be appreciated if this view is obtained tangentially to the glenoid surface. The Y view will best illustrate the acromial arch morphology, and the axillary view can demonstrate concentric reduction and further illustrate joint asymmetry.

normal and that less than 6 mm may suggest an irreparable tear and is suggestive of the need for surgical repair (10). Degenerative joint changes can be appreciated if this view is obtained tangentially to the glenoid surface. The Y view will best illustrate the acromial arch morphology, and the axillary view can demonstrate concentric reduction and further illustrate joint asymmetry.

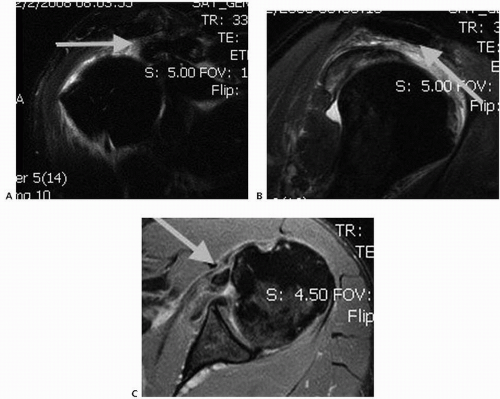

Muscles and tendons are best illustrated with MRI. Europeans have popularized contrast CT to accomplish this goal. An MRI study does not require contrast for an initial exam, but may enhance the evaluation of shoulders previously repaired. The dimensions of the tear can be determined by coronal and sagittal cuts (Fig. 11.3). Transverse cuts will further identify subscapularis and posterior cuff tears.

A finding associated with torn muscle physiology is the development of atrophy and fat infiltration. Medial muscle cuts on sagittal MRI studies can demonstrate muscular deterioration with fatty substitution (Fig. 11.4). Since Goutallier’s et al. original description of the infraspinatus on CT scans, there have been many opinions on the reparability of chronic rotator cuff tears (11). An important question is whether repaired rotator cuff tendons actually heal if advanced stages of fatty infiltration exist. Most would agree that atrophy and fat infiltration are permanent and not reversible. These findings result in muscular weakness that does not improve with surgical repair. Although weakness may be permanent, pain relief has not necessarily been negatively impacted by these changes. For this reason, many patients continue to choose surgical repair as a viable option for a painful rotator cuff tear with moderate muscular changes (12).

Ultrasound has evolved into a dynamic assessment of the rotator cuff (13). The symptomatic shoulder can be easily compared with the opposite extremity and placed through a range of motion. Postoperative repair integrity can also be evaluated and metallic anchors and surgical debris seen on MRI exams can be evaluated with fewer artifacts.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree