9 MASS CASUALTY INCIDENTS

The timing of traumatic incidents is usually erratic. There are slow times with few or no trauma patients, then several traumatic events may occur nearly at once, with each producing more than one patient. Some incidents may produce a larger than usual number of injured persons. Calls for emergency medical services (EMS) trauma response and trauma case arrivals at the hospital occur in this same episodic manner. When the number of injury incidents, or the scope of a single incident, is much larger than usual (a large-scale trauma incident), multiple casualties can result and trauma care systems must rapidly expand capacity to handle the high number of cases.

Various terms are used to refer to large-scale injury incidents. Most have no precise, universally accepted definition. However, the definitions in Box 9-1 provide the reader with an idea of the generally accepted meaning for various terms frequently associated with large-scale trauma incidents. Contingency planning for trauma care under any of these scenarios becomes more challenging as the scope of the event enlarges.

BOX 9-1 Definitions of Terminology Related to Mass Casualty Incidents

Mass casualty incident (MCI): A trauma event in which the needs of numerous injured individuals overwhelm the capability of the trauma center or trauma system.*For example, at a small rural hospital, the arrival of two or more seriously injured patients may be referred to as an MCI, whereas at a larger trauma center the term may apply to an incident producing even more trauma patients, perhaps 5, 10, or more.

Disaster: A sudden natural or man-made event that results in destruction, damage, injuries, or deaths. (See Table 9-1 for examples of events that can cause disaster.)

Weapons-of-mass destruction (WMD) event: Event involving weapons of extraordinary destructive power.

CBRNE: Chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or explosive incident. (This term is now used in favor of the older “NBC,” which stood for nuclear, biologic, or chemical.)

The medical response to any large-scale trauma incident will depend on many factors, including the nature or cause of the incident. Events that cause disasters can be categorized as natural or man-made (Table 9-1). The majority of large-scale disasters worldwide have inflicted physical injuries and deaths. There are several notable examples in which the disaster event inflicted harm simply by exposure to a toxic substance or infectious organisms rather than by direct force. These include the 1984 Bhopal, India, chemical release; the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear power plant incident; the 1995 Tokyo sarin gas attack; the 2002 Moscow theater anesthetic gas incident; and the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic. Exposure to excessive thermal energy can cause burn injuries and deaths, such as happened in the 1996 disco fire in Manila, Philippines. The lack of essential agents, such as food, has led to several large-scale famines, and insufficient oxygen has caused death in the case of mass drownings (e.g., the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami). Many disasters, however, produce physical injuries by direct exposure to kinetic energy (e.g., blunt, penetrating, and blast). An analysis of “significant terrorist events” for a 5-year period (1999-2003) shows that only two of 128 incidents (1.5%) were not caused by direct exposure to kinetic energy, usually a gunshot or explosion; 69% (89/128) were a result of a bombing or explosion.1

| Natural | Man-Made |

|---|---|

Adapted from Dallas CE, Coule PL, James JJ et al, editors: Basic Disaster Life Support Provider Manual, Version 2.5. 2004, American Medical Association.

INITIAL RESPONSE

AT THE SCENE

After the incident is first discovered, EMS and law enforcement groups will be dispatched. As additional details indicate the size of the event, more response units may be requested and dispatched. First-arriving units will assess the scene, making first impressions about the size and scope of the event, and the presence of ongoing safety hazards. One method of approaching the scene assessment uses the familiar ABCDEF mnemonic, as described in Box 9-2.2

BOX 9-2 Mnemonic for Sizing Up the Scene of a Mass Casualty Incident

A Anticipate victims and injuries. What types of injuries can you expect given the nature of the incident?

B Breathing. Is this possibly a toxic environment? Assess for toxic releases.

C Cars/crowds. Look for safety hazards associated with traffic and large crowds of people.

D Disability. What further threatens victims and rescuers? Search for additional hazards, such as unstable buildings and adverse weather.

E Electricity. Look for potential for electrocution from a damaged electrical supply.

F Fuel/fire. Are there spilled fuels or other causes of potential fire, such as natural gas leaks?

Adapted from Augustine J: The ABCs of Size-Up. Emergency Medical Services (EMSResponder.com). Available online at http://publicsafety.com/article/article.jsp?id=2727&siteSection=2 2007. Accessed July 6, 2007.

Organizing Scene Efforts

One useful scheme to organize initial efforts is called the RED survey.3 RED stands for Rapid Evaluation of Disaster. Step 1 of the RED survey is the incident survey (again based on ABCDE) as described in Box 9-3. Part of step 1 is “D = DISASTER,”3 which is another approach aimed at organizing the management of the disaster scene. The mnemonic DISASTER is described in Box 9-4.

BOX 9-3 Incident Survey of the Rapid Evaluation of Disaster

B Barrier. Barrier and Contain refer to efforts to prevent the enlargement of the disaster scene.

D DISASTER (see Box 9-4 for more details)

American Medical Association. Advanced Disaster Life Support Provider Manual (Version 2.0), 2004:1-4 to 1-5.

BOX 9-4 Mnemonic Aimed at Organizing the Management of the Disaster Scene

American Medical Association: Advanced Disaster Life Support Provider Manual (Version 2.0), 2004:1-19.

Triage

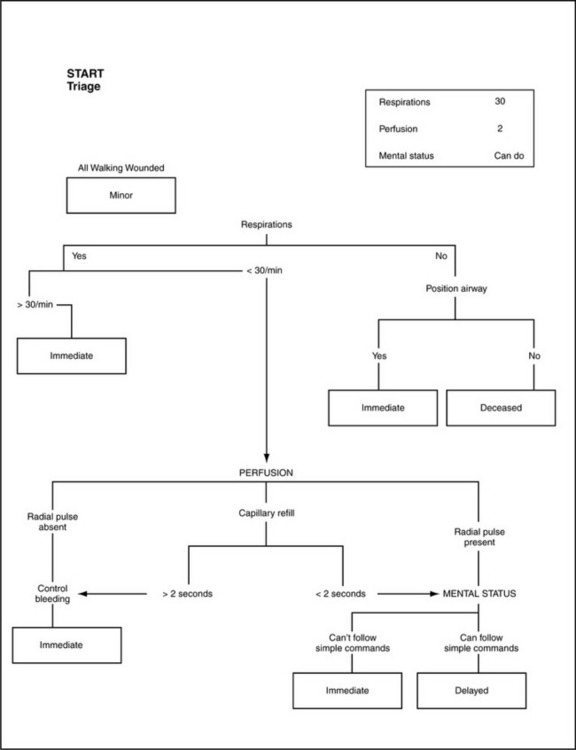

A widely used scheme for multicasualty triage is the START protocol (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment).4 This method (Figure 9-1) effectively categorizes casualties as immediate (red), delayed (yellow), minor (green), or dead/dying (black). Those with impairment to breathing, circulation, and consciousness are categorized as immediate. These are the critical cases that require treatment without delay. The delayed cases may have serious injury, such as fractures or bleeding without shock, but will likely survive some delay in initiation of treatment. The minor cases are often referred to as the “walking wounded.” They should be asked to assemble in an identified area nearby, to be treated when more resources become available. A pediatric modification of this triage method is known as “JumpSTART.”5 Although similar to the START triage method, JumpSTART includes pediatric-specific steps, such as defining respiratory rates differently than in the adult approach.

FIGURE 9-1 START algorithm.

Used with permission from Young K: Simple triage and rapid treatment, START, 1999. Office of Education and Certification, MIEMSS. Available online at http://miemss.umaryland.edu/Start.pdf.

Another useful triage scheme is the MASS Triage model (M = Move, A = Assess, S = Sort, S = Send) with its associated “ID-me!” mnemonic for triage severity categories (I = Immediate, D = Delayed, M = Minimal, E = Expectant).3

Incident Command

As triage continues, additional arriving personnel should establish an incident command center. Usually a senior official of the EMS agency with jurisdiction will take control of this effort. The Incident Command System (ICS)6 is an effective method of bringing organization and control to the complex effort of providing initial care at the disaster scene. An overall incident commander takes control of the entire scene response and all associated major decisions. Assisting the incident commander are any number of possible staff, such as those in charge of:

• Planning—Evaluate information received; develop action plans and strategy

• Finance—Oversee monetary aspects of personnel, staff injuries, and overall event management

• Logistics—Ensure adequate supplies, equipment, water, food

• Operations—Manage scene control, rescue, triage, decontamination, treatment, ambulances, helicopters, other transport, communications, and medical support

AT THE HOSPITAL

First Decisions

Hospital Incident Command System.

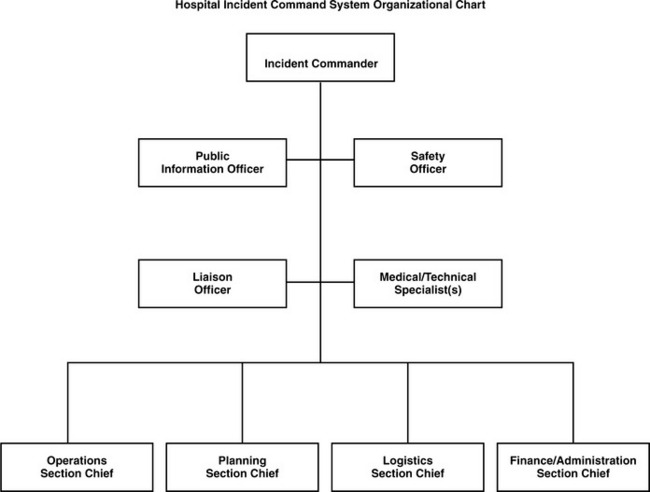

The hospital command center should be opened and an incident commander identified. One good example of an administrative organization for hospital disaster response is the hospital incident command system (HICS) developed by the California Emergency Medical Services Authority.7 The HICS plan calls for a hospital incident commander (IC) to be in charge of all disaster decisions. The IC will be assisted by several section chiefs, typically including the operations chief, the planning section chief, the logistics chief, and the finance/administration section chief. In addition, support for administrative decision making will be provided by a public information officer, a safety officer, and a liaison officer. Additional managers and unit leaders may be organized under the section chiefs, as the scope of the incident demands. The details of a typical HICS organizational chart can be found in Figure 9-2.

FIGURE 9-2 Hospital Incident Command System Organizational Chart.

Adapted from Skivington S, DeAtley C, Saruwatari M et al: Hospital Incident Command System Guidebook. California Emergency Medical Services Authority, 2006. Available online at http://www.emsa.ca.gov/hics/hics guidebook and glossary.pdf.

The HICS is outlined in great detail in the Hospital Incident Command System Guidebook,7 which is available online for download. All appropriate hospital leaders and key medical staff members should be thoroughly trained on the HICS system. Many such personnel will not want to devote the time necessary to this training. As a result, HICS education and practice exercises should be of the highest quality, providing realistic scenarios that demand that the participants think critically and thoroughly explore the implications of the various HICS roles. Practice drills and exercises with realistic scenarios should be conducted on a regular and frequent basis (such as quarterly). These approaches will demonstrate the relevance of the HICS education and enhance administrative commitment to devoting the time necessary to training. The “Introduction to ICS for Healthcare/Hospitals” (IS 100 HC) course and the “Applying ICS to Healthcare Organizations” (IS 200) course are available online.6

The preestablished hospital command center should be located in an area likely to remain accessible during a disaster, large enough to accommodate the command staff, and stocked with all needed supplies and equipment. Communications equipment is particularly critical, including multiple telephone lines, radio communications, and computer systems. The command center should be able to view multiple television channels simultaneously, project video, and have communication tools available to support decision making such a white boards, charts, and flip charts. Regional maps, hospital architectural plans, copies of hospital and community disaster plans, personnel and supply inventories, job action sheets, and other disaster supplies and equipment should be on hand. Frequent HICS practice exercises should take place involving the hospital command center so that all HICS leaders are familiar with its capabilities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree