Robert L. Barrack

Managing the Patella in Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty

ISOLATED REVISION OF A FAILED PATELLAR COMPONENT

RETAINING A WELL-FIXED PATELLAR COMPONENT

TREATING THE DEFICIENT PATELLA

OPTIONS FOR THE DEFICIENT PATELLA

INTRODUCTION

At the time of revision total knee arthroplasty (TKA), the patella is frequently the last component addressed at the time of surgery, and therefore its importance is often minimized or neglected. Frequently, however, patients undergoing a revision TKA will have anterior knee pain or symptoms preoperatively, and a careful evaluation of the patellofemoral tracking and extensor mechanism should be performed. Poor extensor mechanism function following revision TKA is a leading cause for persistent pain, limited function, and a compromised result. As Rand stated, “the patella has too often been neglected in discussions of TKA revision.”1 Many studies on revision TKA do not even specify on the method of patellar treatment. Despite this, there are a number of potential treatment options for the patella. Prior to selecting the method of treatment for a problematic patella in TKA, the attention should be focused on femoral and tibial component rotation, as this may be the primary mode of failure of the patellar implant if incorrect rotation is present. Careful preoperative planning, intraoperative decision making, and availability of specialized implants, instruments, and bone grafting techniques will allow the surgeon to prepare for patellar revision options. Assessment of implant stability, type of existing implants, and remaining host bone stock are factors to consider in the planning process. Management of the deficient patella with poor remaining bone stock poses a challenging problem. Several techniques have been described for dealing with these difficult patellar problems encountered during revision TKA. The purpose of this chapter is to review the general surgical principles in approaching the patella during revision TKA, to discuss the options available for patellar management, to review and update the previously documented results of these traditional options, and to describe the new techniques for patellar treatment in revision TKA.

BIOMECHANICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The patella acts as a dynamic fulcrum to transmit the forces generated by the extensor mechanism through the knee and may be responsible to provide up to 50% increase in knee extension compared to the knee without a functioning patella or patellectomy.2 The contraction of the quadriceps mechanism has been associated with contact pressures exceeding 6.5 times body weight at the patellofemoral joint. It has been proposed that anterior knee pain following TKA may in fact be secondary to altered biomechanics3,4 at the patellofemoral joint. Increased patellofemoral joint forces are present with increased degrees of flexion,5–7 which is one measure of success in TKA outcome. It has been shown that higher flexion concentrates forces onto the lateral superior and medial facets of the patella.6 The resurfaced patella has been reported to be subjected to increased strain and decreased tensile strength by as much as 30% to 40%.8 The decreased thickness of bone, combined with osteopenia, may be a factor predisposing to patella fractures in the resurfaced patella. This may be worsened when combined with a lateral retinacular release, which may potentially devascularize the extensor mechanism.9,10 Thus, multiple biomechanical factors may contribute to patellar component or host bone stresses in association with a TKA.

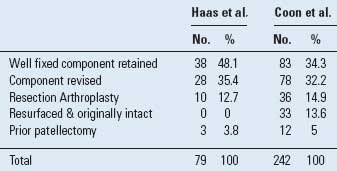

The method of treatment of the patella in revision TKA has been well described in recent studies, and a spectrum of patellar problems and treatment options has been identified in a recent review.11 In a study of 79 revision TKAs reported by Haas et al.,12 in 38 knees a well-fixed component was left in place, in 28 knees the patellar component was revised to a new component, in 10 knees the component was resected and left unresurfaced, and in 3 knees a patellectomy was performed. In a multicenter study of 242 revision TKAs reported by Coon et al.,13 a similar distribution of patellar treatment options was reported (Table 48.1). The study by Coon et al. concluded that the method of patellar treatment significantly impacted the clinical result. Patients who had a revision TKA with prior patellectomy or with patellar resection arthroplasty had significantly worse results compared to the other groups.

The first priority in the treatment of the patella in revision TKA is to avoid extensor mechanism disruption in the form of either a patellar tendon avulsion or patella fracture. This begins with the surgical approach to the knee at the outset of the case. Exposure of the patella is necessary to assess the status of the patellar implant and to proceed with the definitive treatment. This should be accomplished in a careful, sequential manner. The patella should not be immediately everted while flexing the knee past 90 degrees, as is often possible in a primary TKA. The gutters should be cleared of adhesions, particularly on the lateral side. The patella should be placed under tension with a laterally directed retractor while adhesions are released starting with the patellofemoral ligament. While eversion of the patella is preferred for the exposure, the patella may be partially everted or slid laterally (without complete eversion) with similar exposure and less stress on the extensor mechanism. If undue tension on the patellar tendon insertion is still apparent with attempted patellar eversion or a slide, an alternative surgical approach should be considered.14 After patellar exposure has been accomplished, it is necessary to expose the interface between the patellar component and the underlying bone. Frequently this interface is obscured by overlying fibrous tissue/meniscus.15 This should be circumferentially removed and the interface examined. An osteotome can be placed under the patellar component to determine if it can be levered out. However, levering on a thin patellar remnant may cause iatrogenic injury or fracture and should be avoided if the component appears well fixed. Occasionally a component that appears well fixed radiographically will prove to be loose when tested in this manner. If the patella is not loose, radiographically or at intraoperative testing, a decision must be made as to whether there are other indications for removal of the component.

TABLE 48.1 Methods of Patellar Treatment in Two Series of Revision TKA

After a definitive method of patellar treatment has been elected, the final surgical consideration is ensuring optimal tracking of the extensor mechanism. This is equally important regardless of the method of patellar treatment elected. The major methods of optimizing tracking include attaining appropriate prosthetic rotation, especially an appropriate degree of femoral component external rotation. This is most reliably obtained in the revision situation by aligning the femoral component with the epicondyles. Tibial component internal rotation should be avoided, and generally alignment of the midportion of the tibial component just medial to the midpoint of the tibial tubercle will position the component appropriately.16 If the extensor mechanism does not track centrally, the femoral and tibial component rotation should be carefully reassessed with these landmarks in mind, as the magnitude of combined internal rotation of the implants has been shown to be directly proportional to the degree of patellar maltracking on radiographs.16 In one study of patellar dislocation in TKA, patellar tracking only improved after soft tissue realignment in combination with revision of malaligned or loose components was performed. Although revision significantly improved active knee extension and knee scores, two thirds of the patients had residual disabilities and pain.17

Certain component-positioning parameters can place undue stress on the extensor mechanism. If the anterior flange of the femoral component is placed anteriorly (flexed) so that the flange is not flush with the femoral cortex, this will increase the forces on the extensor mechanism during knee flexion. Elevation of the joint line will produce a similar effect. If a very thick tibial polyethylene tibial insert is used and there is undue stress on the extensor mechanism with knee flexion, the position of the patella relative to joint line should be carefully assessed. The joint line is normally approximately 1.5 to 2.0 cm above the fibular head, and in extension the inferior pole of the patella should be approximately >1 cm proximal to the surface of the tibial insert (range: 1 to 4 cm on lateral radiograph). If a thick tibial insert is necessary to obtain stability in extension and this results in a relative patellar baja, consideration should be given to using distal femoral augments and a thinner tibial insert to effectively lower the joint line.

Once the patellar component has been adequately exposed and its fixation status has been assessed, a decision must be made regarding the optimal method of treatment for the patella. If removal of the patellar component is elected, there are certain surgical technique considerations. The patellar component should be stabilized, usually with towel clips through the quadriceps and patellar tendons, with care to avoid clipping and tension at the insertion of these tendons onto the patella. If the remaining patellar component bone is overly thick (>15 mm) it may be possible to simply take a saw and undercut the pegs of the component. This is not frequently possible. A well-fixed all-polyethylene patellar component however can still be removed by placing a saw blade right at the implant-bone interface and sawing off the polyethylene from the pegs. The cement and pegs may then be removed with narrow sharp osteotomes or a pencil-tipped burr, with care being taken not to fragment the residual patellar bone. Well-fixed polyethylene cemented pegs can be efficiently removed by drilling the center of the peg with a sharp drill bit; this should be performed with caution, in order to avoid perforation through the anterior cortex and further stress riser creation in the patella. This will remove the polyethylene from the cement and the cement may then be removed with sharp curettes and small osteotomes, again with care being taken not to fragment the bone.

When a metal-backed component is removed, it is usually easier to first remove the polyethylene from the metal. Cemented metal-backed components are carefully removed with osteotomes around the periphery. The most difficult component to remove is the bone-ingrown metal-backed component. A diamond-wheel cutting tool is used to side-cut the lugs at the junction of the baseplate.18 If the revision is for an aseptic diagnosis, leaving the well-fixed lugs in place and cementing the revision component over the host bone and lugs have been described.11 Certain metal-backed patellar component designs are extremely difficult to remove without loss of significant patellar bone. In this situation, sectioning the metal baseplate has been suggested as a method of minimizing the risk of patellar fracture during component removal.19 The decision to remove a metal-backed patellar component should be made for components that show significant wear of the polyethylene, component malposition, or extensive underlying osteolysis. If the component is metal backed and does not have these characteristics, then it may be reasonable to retain the implant if the tracking and geometry of the components are suitable.

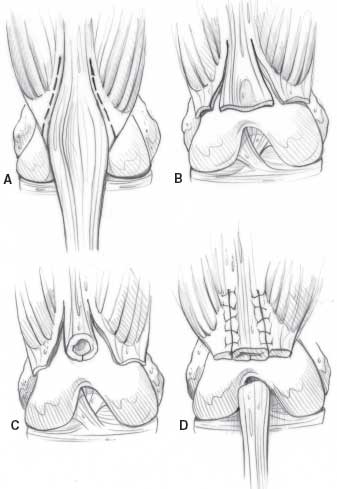

The most commonly selected options for patellar treatment are to either leave a well-fixed patellar component in place (occurs ~30% to 50% of the time20,21) or to revise the patellar component to one that is specific for the revision component being implanted. After patellar component removal, there may not be enough residual bone to implant a standard three-peg patellar component. Generally, if greater than or equal to 10 mm of bone is remaining throughout the patella, an adequate implant fixation with an all-polyethylene onlay cemented implant may be obtained. When less than this amount of bone remains, the surgeon is faced with a more challenging problem. In this scenario, a number of options exist, including using a biconvex revision component, leaving the residual bone unresurfaced, using a “crossed K-wire” technique to reinforce a cemented central peg patella, impaction grafting using a bone graft contained in a synovial pouch, a porous metal patella that has both bone and soft tissue ingrowth potential, and using the so-called gull-wing osteotomy. Another clinical scenario occasionally encountered is a patient with a TKA and a prior patellectomy. This group of patients has traditionally had the least optimal results. Attempts to reestablish some of the mechanical advantages of the patella in this scenario include tubularization of the residual extensor mechanism (Fig. 48-1),22 iliac crest bone grafting, or attaching a patellar ingrowth component to the soft tissue of the residual extensor mechanism. These treatment options and the clinical results that have been described to date are discussed.

FIGURE 48-1. “Tubularization” attempts to improve the cosmetic appearance as well as the mechanical lever arm of the extensor mechanism after patellectomy A: Retinacular medial and lateral incisions. B: Paterla is excised. Note the extension mechanism is not transferred. C: The extensor mechanism (quadriceps patellar soft tissue sleeve patellar tendon). D: The retinaculum is switched back to the tubularized extensor mechanism. (Adapted from Callaghan JJ. The adult knee. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

ISOLATED REVISION OF A FAILED PATELLAR COMPONENT

The patient who presents with a failed patellar component in association with a TKA should be carefully evaluated. The temptation to proceed with an isolated revision of the patellar component alone should be undertaken with caution, and a more thorough evaluation performed to assess the mode of failure. Although rarely an isolated revision of the patella is necessary, the surgeon should approach such cases with caution, and search for a primary mode of failure or extensor/component malalignment. A careful clinical history, physical examination, and serial radiographs should be obtained. Radiographs made prior to the index arthroplasty are useful to assess the preoperative tracking of the native patella. If there is patellar maltracking, subluxation, or dislocation, the rotation of the tibial and femoral components can be evaluated with a CT scan for axial rotational measurements. The surgeon should assess for the combined internal malrotation of the components, which correlates with the degree of lateral patellar tracking problems.16,23 If there is a combined degree of abnormal internal rotation, this requires revision of the component(s) in order to restore extensor mechanism tracking and create patellofemoral stresses closer to normal. Isolated revision of the patellar component in a revision TKA is a procedure that has reported poor results in a substantial percentage of cases, likely secondary to unrecognized component malrotation. Koh et al.24 reported on the results of 29 knees undergoing isolated revision of patellar metal-backed components at 2 to 9 years of follow-up in patients with a mean age of 71 years.24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree