Managing Patella Problems in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty

Richard A. Hocking

Steven J. MacDonald

The incidence of postoperative problems and complications with the patella in primary knee replacement has fortunately been significantly reduced with a better understanding of the effects of component position and rotation on patellofemoral mechanics and in particular with the development of femoral components that have been designed to assist patella tracking. However, there remain several specific clinical scenarios in which the patella and/or the extensor mechanism present unique challenges to the reconstructive surgeon. These specific situations are the subject of this chapter.

Modern femoral components have an impact on patellar performance. They are side-specific and have a prominent anatomically designed trochlear groove, which proximally sweeps laterally to capture the patella in extension. The groove then sweeps medially to draw the patella between the medial and lateral condyles as the knee is flexed. Modern designs accommodate the morphology of both the native patella and a prosthetic patella whether the patellar prosthesis is an inlay or an onlay design.

The soft tissues also affect the tracking of the patellar tendon. The ability of the patella to track physiologically is determined by the balance of the forces exerted through the soft tissues around the knee. Manipulating these forces allows the surgeon to balance the patella. Extreme situations such as altered height of the patella, chronic dislocation of the patella, erosion of the patella, or absence of the patella have profound effects on these forces and are the subject of this chapter.

LATERALLY DISLOCATED PATELLA

Indications

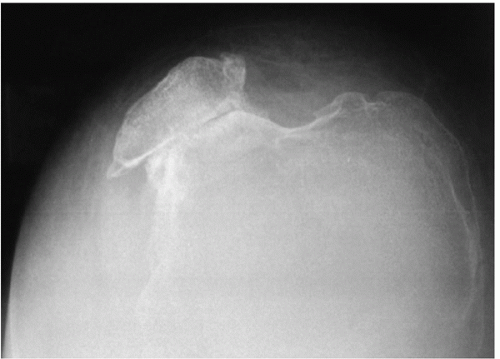

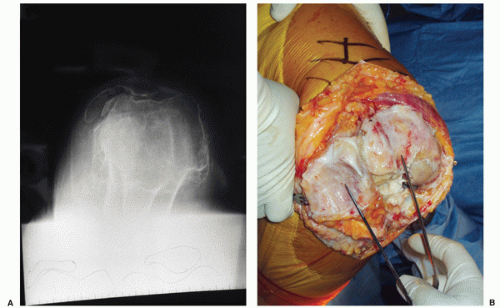

On occasion, patients present with a laterally subluxed or chronically dislocated patella, which may be caused by congenital or acquired disorders of the patella. Congenital patella dislocations may occur in patients with Nail-patella syndrome in which there is a small, high patella. The majority of the patellae that present dislocated are acquired dislocations caused by secondary mechanical alignment changes of the limb (usually severe valgus) (Fig. 14-1) and erosions of the patella articular surface (more common in advanced rheumatoid arthritis) (Fig. 14-2A,B). The challenge in these situations is first to reduce the dislocations and then to achieve stability throughout the arc of motion.

Preoperative Preparation

Preoperative evaluation includes thorough history, examination, and radiological investigation. In the history, the nature of the onset and the duration of the dislocation should be sought. Symptoms of instability, particularly with single-leg weight bearing and loss of power in the affected knee are important to elucidate.

Physical examination should be directed at establishing the position of the patella in relation to varying positions of flexion. Is the patella always dislocated? Is it dislocated only in flexion (suggesting tight lateral structures and a contracted extensor mechanism), or does the patella reduce in deep flexion while being unstable in early flexion (suggesting either patella alta or a poorly formed trochlea)?

Imaging studies should include a standing 3-foot anteroposterior, lateral, and intercondylar views. A skyline view of the patellofemoral joint is also required. In these views, the anatomical and mechanical axes should be determined. The majority of cases with patella dislocation will be in knees with significant valgus deformity. The skyline view usually reveals a shallow or dome-shaped trochlea with a patella that has suffered erosion to conform to the dome-shaped trochlea (Fig. 14-2A). Although magnetic resonance imaging or computer tomography scans can be helpful for assessing the extent of bony erosions preoperatively, this additional information is generally unnecessary as long as the surgeon anticipates erosive changes and plans appropriately.

TECHNIQUE INCLUDING PEARLS AND PITFALLS

The surgeon approaches the knee via a midline incision and medial parapatellar arthrotomy. The medial release is initially kept to a minimum in keeping with the routine valgus knee exposure. An attempt is then made to evert the patella, which may or may not be successful at this stage. If successful, the surgeon continues with the preparation for implanting the tibial and femoral components, paying careful attention to the alignment and rotation of the components (information to follow). If the surgeon is unsuccessful in everting the patella, a decision needs to made as to whether the existing exposure is adequate to correctly orient the femoral and tibial components. If the existing exposure with lateral subluxation/dislocation of the patella without eversion is adequate, I continue with preparation for implantation. If the exposure is inadequate, the exposure needs to be improved by eversion of the patella.

Eversion of the patella may be achieved by performing a lateral release. My preference is to perform the release from inside the knee to outside. The patella is lifted anteriorly with one hand, and using a knife or electrocautery, the tight lateral retinaculum is divided. Initially, the retinaculum is divided immediately adjacent to the patella. An attempt at eversion is made, and if this is not successful, the retinaculum superior and inferior to the patella is palpated for tightness, and the release is extended accordingly. The release is continued until the patella is able to be everted.

The preparation of the proximal tibial and femoral surfaces is completed as outlined in Chapter 5, and coronal soft tissue balancing is addressed as outlined in Chapter 9, after which the patella is addressed. I prefer to resurface the patella with an inlay component (1). The thickness of the patella is determined with calipers. If the patella is less than 12 mm thick, the risk of a fracture either with intraoperative preparation or in the postoperative period is increased, and I will therefore leave that patella unresurfaced (2). I try to maximize the size of the patella button, and I center it on the patella bone to allow for the largest size patella. If the bone stock is adequate, I try to maximally medialize the patella button to enhance patella tracking, using the smallest patellar component possible so as not to compromise the lateral patellar facet if it is very thin and risks fracture. The patella is then reamed to a preset depth to allow seating of the implant inside a rim of bone. With the trial button in place, I remove excess bone using the oscillating saw such that there is a smooth transition from the prosthetic patella to the host patella surface. This creates a dome-shaped structure with the prosthetic patella at the center.

The knee is then put through a range of motion (ROM) with the trial components in place. The corrections to the coronal plane alignment are often all that is necessary to keep the patella balanced, particularly if a lateral release had been done during the approach. If the patella is not reduced at this stage, and a lateral release was not performed earlier, it is performed at this stage, after the tourniquet has been released and patellar tracking has been reassessed (Fig. 14-3) (3). The surgeon performs the release using a scalpel or electrocautery from inside the joint starting with the retinaculum immediately adjacent to the patella and then continuing the release proximally and distally as required. The knee is then put through a ROM, and the stability of the patella is assessed. It is important to distinguish between a patella that tends toward a tilt, versus those that are subluxing or dislocating. If the patella is simply tilting, one or two towel clips are used to approximate the medial arthrotomy closure, and patellar tracking is reassessed. In the vast majority of clinical scenarios, this simple move will resolve the tilt. Rarely, the patella may continue to dislocate as the knee goes into

deeper flexion. The approach then is to tighten the medial side to see whether this will balance the forces across the patella (Fig. 14-4

deeper flexion. The approach then is to tighten the medial side to see whether this will balance the forces across the patella (Fig. 14-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree