Managing Medial Collateral Ligament Deficiency with Soft Tissue Reconstruction

Kenneth A. Krackow

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Loss of ligament stability in total knee replacement, both in primary and revision situations, is commonly addressed by increasing the prostheses’ constraint (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). But use of constrained prostheses, particularly rotating hinges, as well as constrained intercondylar prostheses (CIPs), may not be an optimal solution. This is particularly true in younger active patients, as shown by numerous studies (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Furthermore, major reliance on the constrained prosthesis alone may not lead to success if the prosthesis is used without adequate soft tissue balance.

There are special situations in primary total knee replacement in which ligament loss or incompetence is encountered, either preoperatively or intraoperatively, and our preferred techniques for managing these situations are described herein. This ligament advancement or reconstruction approach is used at the time of knee arthroplasty to adjust major soft tissue sleeve imbalance caused by ligament loss or incompetence. It is not used as a technique for managing unstable total knee arthroplasty at a second separate procedure. Also, this chapter deals with ligament incompetence situations, not soft tissue balance techniques in general, which usually involve releasing tight structures on the concave side of a deformity and which are covered in Chapter 9.

Ligament imbalance in a primary total knee can be managed by different methods:

Soft tissue balancing (generally done by releasing tight structures on the concave side of the deformity)

Ligament reconstruction (which may include proximal and distal advancement of ligaments or ligament substitution or augmentation)

Constrained prostheses (which may range from total stabilizing to a hinged prosthesis)

A combination of any two or more

We use the term CIP to indicate total knee components with intra-articular “peg” mechanisms that provide medial lateral and posterior stability. This term has been adopted to provide a generic alternative to the cumbersome attempts at not favoring a particular brand by simultaneously always mentioning two or three, for example, constrained condylar knee, total condylar III, superstabilizer, and others.

We define ligament loss or incompetence as a situation in which the ligament is either stretched and attenuated or injured and in discontinuity. In these situations, releasing the opposite side to balance the soft tissue sleeve may not be an ideal solution. It may likely be impractical to expect to lengthen the now relatively tight side enough to balance out to an abnormally lengthened position assumed on the damaged side. Also, neither the original damaged side nor the released surgically lengthened side will possess normal ligament strength. Therefore, ligament reconstruction or the use of a more constrained prosthesis or a combination of both may be necessary to achieve adequate stability.

CIPs have been shown to have encouraging results in the intermediate-term follow-up in elderly patients with low physical demand (3). In individuals who are younger and more active, however, the constrained knee may transfer stress to the implant-cement-bone fixation interface and may lead to early failure. Therefore, to avoid excessive prosthesis constraint in patients who are not elderly, ligament reconstruction can be a workable alternative. Key features of the indications for soft tissue advancement or reconstruction as described in this chapter relate to a strong desire to avoid the use of a CIP.

It should also be clear that we are dealing with a situation that by definition is not amenable to a solution by use of posterior-substituting components alone. Most posterior-stabilized components provide no collateral stability; they provide posterior stability and some medial lateral translation stability.

PREOPERATIVE LIGAMENT LOSS

Preoperative ligament loss can be the result of traumatic ligament injury or stretching, or as part of these a priori primary deformities.

Valgus Deformity

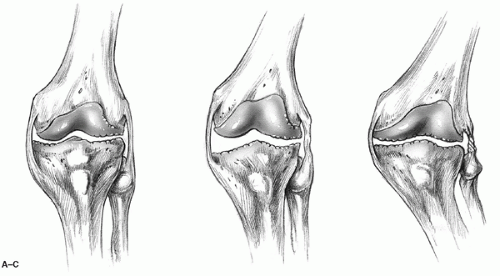

Valgus deformity in an arthritic knee may be classified as type I, type II, or type III (Fig. 18-1A—C) (6,7). The type II valgus knee is found in a small subgroup of patients with greater bony deformity with two specific soft tissue problems: lateral soft tissue contracture and medial soft tissue attenuation. Medial ligament reconstruction procedures are considered in those cases in which adequate medial stability has not or cannot be achieved, despite essentially maximum soft tissue release. Such release would include posterior cruciate ligament release or recession and extensive release of lateral collateral structures.

While considering special deformity situations that may be addressed by ligament reconstruction technique, it may also be appropriate to consider and discuss type III valgus deformity. An example of this is a severely overcorrected closing wedge-style proximal tibial osteotomy as a result of malunion, late collapse, wear in the lateral compartment, or overcorrection at the time of surgery. This situation is not exactly an example of ligament damage or incompetence, but its management is unusual and fits in with other techniques discussed in this chapter.

In this situation, in addition to the grossly abnormal valgus-oriented proximal tibia, there is an asymmetry of the soft tissue sleeve, which is different from the average valgus knee. The dissection at the lateral aspect of the knee and soft tissue handling of the iliotibial band and lateral collateral ligament during the previous proximal tibial osteotomy together can make the standard lateral soft tissue release more difficult. Achieving sufficient lateral release in any of these examples to achieve simultaneous balance of collateral ligaments and the normal 6 degrees of valgus tibiofemoral angle may simply be impossible (8,9). Therefore, medial ligament reconstruction may be considered to achieve adequate balance, particularly in younger active individuals in whom we want to avoid excessive constraint. Furthermore, in our experience, the tibial osteotomy is done in the younger age group, and the truly overcorrected example becomes a major problem within 18 months to 2 years after osteotomy. Therefore, patients with type III valgus presenting for treatment are relatively young patients in whom the surgeon would like to avoid the use of a CIP.

Today, type III valgus knees may also be managed by simultaneous tibial osteotomy during arthroplasty, with fixation using press-fit intramedullary stems. The complex ligament reconstruction procedure was developed before such implants became available (8). Other options, such as

corrective osteotomy alone could even be considered for some cases. TKA should be offered only when the patient is, in general terms, considered an arthroplasty candidate because of significant intra-articular degeneration requiring joint resurfacing.

corrective osteotomy alone could even be considered for some cases. TKA should be offered only when the patient is, in general terms, considered an arthroplasty candidate because of significant intra-articular degeneration requiring joint resurfacing.

Procedures

The following procedures are indicated for preoperative ligament loss, depending on the nature of the injury. Medial collateral ligament (MCL) reconstruction is indicated for preoperative traumatic MCL injury and type II and type III valgus deformity.

INTRAOPERATIVE LIGAMENT LOSS

MCL

The MCL is probably the most common collateral ligament injured intraoperatively. The exact incidence of this complication is not known. In our personal experience, it is less than 1%. There are reports of an incidence rate as high as 8% in a selected group of morbidly obese individuals (10). Whatever the incidence may be, intraoperative disruption of MCL injury could cause significant soft tissue imbalance and late postoperative medial instability with valgus deformity.

Situations in which there is a high risk of injuring the MCL intraoperatively are as follows:

Markedly obese individuals with difficult exposures

Tight varus knees, typically with overhanging medial femoral and tibial osteophytes

Surgical inexperience

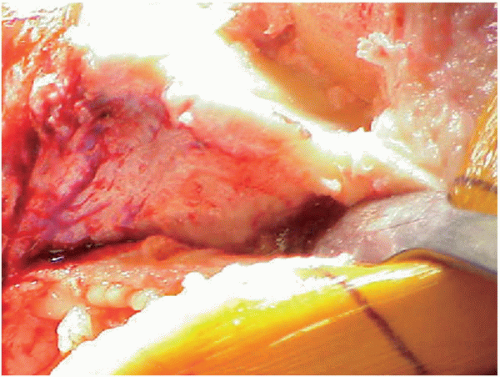

FIGURE 18-2 Subperiosteal dissection of the medial tibial condyle and placement of the retractor under the medial collateral ligament. |

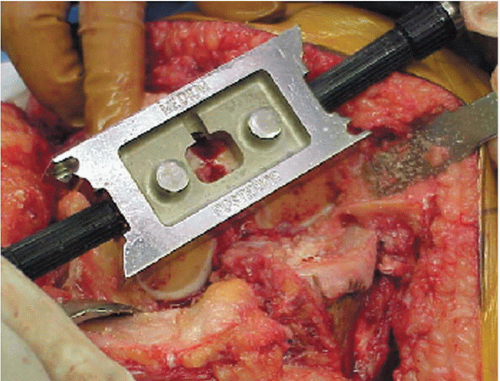

FIGURE 18-3 Protecting the collateral ligaments by placing the retractors at the same level as the saw blade while doing bone preparation. |

Intraoperative MCL injury occurs when the surgeon fails to remain close enough to the bone and dissect under the MCL at the medial tibia, just below the osteophyte. In certain cases, the superficial MCL remains closely apposed to the bone here. The surgeon or the assistant who does not appreciate this fact may lacerate the MCL if it is not adequately retracted during sharp dissection when attempting to uncover the osteophyte, during sawing the tibial or posterior femoral cut, or while excising the medial meniscus without proper tension or exposure.

Clearly, the best practice is to avoid injury. Surgical tips to avoid injuring the MCL include the following:

Medial tibial condyle dissection must be subperiosteal and therefore deep to the MCL.

Placement of an elevator or retractor must clearly be under the MCL (Fig. 18-2) on bare bone.

The collateral ligaments should be protected by placing appropriate retractors while performing the bony preparation (Fig. 18-3) and making certain that the retractors are at the same level as the saw blade.

Release the mid and posterior midmedial capsular margin and deep MCL before cutting the medial tibia (Fig. 18-4) so that it is possible to perform adequate protecting retraction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree