Management of Labral and Articular Lesions

Carlos A. Guanche

Our understanding of the pathology causing hip pain is evolving. The exact prevalence of acetabular labral tears and cartilage injuries in the general population is unknown. Injuries to the acetabular labrum are the most consistent pathologic findings identified at the time of hip arthroscopy (1). In one review of 300 cases, labral tears were present in 90% of patients. These tears are most frequently found in the anterior aspect and often are associated with sudden twisting or pivoting motions. The incidence of cartilage injuries is as not as well documented, however.

Current surgical options as well as the indications for surgery are being developed. The ideal indication for labral repair is a tear from a recent traumatic injury. The common presentation, however, has no inciting event and is caused by chronic repetitive injury, leading to an attritional tear. Likewise with cartilage injuries, there is typically a long history of chronic pain with no obvious etiological event. It is therefore important to understand that treatment of the underlying pathology is as important as treating the problem, or the long-term results will be poor.

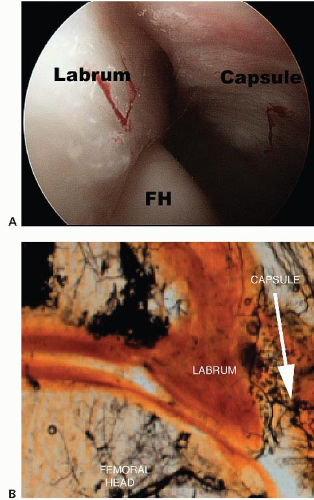

The hip labrum is a fibrocartilaginous structure that surrounds the rim of the acetabulum in a nearly circumferential manner. The labrum is widest in the anterior half, thickest in the superior half, and merges with the articular hyaline cartilage of the acetabulum through a transition zone (2) of 1 to 2 mm. The labrum is firmly attached to the rim of the acetabulum. Its junction with the osseous margin is irregular, and there may be extension of bone into the substance of the labrum. A group of three or four vessels are located in the substance of the labrum on the capsular side of this bony extension and penetrate into the peripheral one-third of the labrum. The labrum is separated from the hip capsule by a narrow synovial-lined recess (Fig. 48.1). Extrapolating from our understanding of the healing capacity of the meniscus, repair strategies should be considered in tears involving only the peripheral labrum.

We are only beginning to understand the function of the labrum. It functions as a secondary stabilizer by extending the acetabular congruity as well as helping to maintain the negative intra-articular pressure within the joint. This has been confirmed through a poroelastic finite model that showed the labrum functions to provide structural resistance to lateral motion of the femoral head within the acetabulum (3) and decreases the contact pressures within the hip probably as a result of its effect on maintaining the articular fluid in contact with the weight-bearing cartilage (4).

CLINICAL EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

Since the differential diagnosis of hip pain is so broad, the examiner must detail the patient’s history with regard to their medical history, any hip surgery/trauma, or pediatric hip disease, as well as any social or occupational hazards. The clinical presentation of patients with a tear of the labrum or chondral injury is variable, and, as a result, the diagnosis is often missed initially. One study has shown that in a series in which the diagnosis of a labral tear had been made by arthroscopy, the mean time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 21 months (3). An average of 3.3 health care providers had seen each patient prior to diagnosis. Groin pain was the most common complaint (92%) with the onset of symptoms most often insidious. The most common exam finding was a positive “impingement sign,” which occurred in 95% of patients in this series.

Although most patients do not specifically report loss of hip range of motion, this finding is almost universally seen. Hips with structural abnormalities, such as acetabular retroversion, coxa profunda, or pistol grip deformities, may have decreased range of motion(ROM) from anatomic limitations, but may also be limited by pain. Patients with pathologic hip conditions also commonly develop late capsulitis, synovitis, and/or trochanteric bursitis. Differential diagnosis of the classic mechanical symptoms (painful catching or clicking) of labral tears and/or chondral injury includes snapping iliotibial tendon or a hypermobile psoas tendon (1). The differential diagnosis should include sacroilitis, degenerative disk disease, abductor muscle problems, osteonecrosis, psoas tendinitis, pubic rami fractures,

and stress fractures of the proximal femur. More chronic problems are usually associated with trochanteric bursitis.

and stress fractures of the proximal femur. More chronic problems are usually associated with trochanteric bursitis.

Clinical examination of the affected hip should begin with an evaluation of the patient’s gait, foot progression angle, and measurement of leg length. The antalgic gait pattern should be differentiated from the Trendelenburg gait (seen in patients with hip dysplasia who have weak abductors). Patients with deformities secondary to slipped capital femoral epiphysis may ambulate with an externally rotated extremity and an open foot progression angle (>10°). Hip pathology may be detected on inspection of the lower extremity rotation with the legs at rest. Typically, both feet rest symmetrically at approximately 10° to 30° of external rotation. Asymmetric external rotation of the legs may indicate acetabular retroversion, femoral retrotorsion, or femoral head-neck abnormalities, which can be a source of primary pathology.

The hip is then carried through a range of motion, with one hand placed over the spinous process during flexion to allow immediate detection of pelvic flexion once the proximal femur contacts the acetabulum. Rotation is then measured with the hip flexed at 90°. The patient with retroversion and femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) has limited flexion and/or internal rotation.

Findings on physical examination can include a positive McCarthy sign (with both hips fully flexed, the patient’s pain is reproduced by extending the affected leg, first in external rotation, then in internal rotation). Also common is inguinal pain with flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the hip as well as anterior inguinal pain with ipsilateral resisted straight leg raising (5).

The impingement test was first described for patients with femoroacetabular impingement but is equally useful for labral injuries. With the hip at 90° of flexion, maximum internal rotation and adduction is performed. Contact between the anterosuperior acetabular rim and the femoral neck elicits pain. Although there is no specific examination to assess for chondral injuries, this same maneuver is also highly sensitive for intra-articular patholog (6). The hip can also be tested at varying degrees of flexion. Posterior labral tears should be tested with the leg externally rotated and in hyperextension.

Diagnostic Imaging

Weight-bearing AP pelvis and frog lateral radiographs are critical in the initial assessment to evaluate the patient for arthritis and FAI, as well as dysplasia.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the superior accuracy of magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) over standard MRI in diagnosing labral tears. Intra-articular gadolinium has been shown to improve the sensitivity of diagnosing labral pathology from 25% to 92% using a small field of view (7). Therefore, when clinical suspicion of a hip labral tear or chondral articular disruption exists, MRA using a small field of view is the study of choice.

An intra-articular bupivacaine injection may be useful in situations where the diagnosis of labral or chondral pathology is equivocal or if a tear has been diagnosed by MRA, but it is uncertain whether symptoms are related. Similar to its use in diagnosing external impingement of the shoulder, if patients experience relief from their symptoms following the injection, the diagnosis of pain secondary to hip intra-articular pathology is more certain (8). However, intra-articular pathology could still be present without pain relief from the injection (9).

Research utilizing delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC), which measures loss of glycosaminoglycans in early stages of arthritis, has demonstrated that dGEMRIC has the ability to detect early stages of osteoarthritis due to hip dysplasia and femoroacetabular impingement (10). In addition, this technique has shown promise with regard to staging of cartilage lesions before and following surgical interventions.

TREATMENT

Nonoperative

Once the diagnosis of a labral tear has been made, conservative treatment options include avoiding activities that cause symptoms and a supervised therapy program emphasizing hip range of motion and core strengthening. Although it is unlikely that the tear will heal over time, it is possible that symptoms may stabilize to the point that the patient no longer experiences symptoms. If conservative management is elected, the patient should understand the need to avoid activities that produce symptoms and the possibility that the tear may progress and potentially predispose to arthritic changes in the hip. There are no published series detailing the long-term results of this treatment regimen.

Likewise, the mainstay of treatment for cartilage injuries consists of prompt diagnosis and activity modification. If these fail to ameliorate symptoms, surgical treatment is recommended. There are numerous accepted surgical options most of which are based on the historical treatment of these injuries in the knee. The procedure depends on the underlying etiology, overall alignment of the joint, the extent of involvement, and size of the lesion. For more advanced processes, treatment options include acetabular and femoral osteoplasties, redirectional osteotomies, trap-door procedures, hip resurfacing, and total joint replacement. For well-circumscribed lesions in a prearthritic well-aligned joint, options include debridement, microfracture, and isolated cartilage restoration as well as resurfacing procedures. Although open surgery is still the gold standard, these procedures are increasingly being performed arthroscopically.

Operative Debridement of Lesions

Most labral tears and chondral injuries are treated with debridement. However, some labral tears are amenable to arthroscopic repair. As discussed, the blood supply to the labrum enters from the adjacent joint capsule, with vascularity detected in the peripheral one-third of the labrum while the inner two-thirds were avascular. Thus peripheral tears have healing potential, and repairs should be considered if this is observed at the time of surgery. However, McCarthy et al. (6) reported 436 consecutive hip arthroscopies including 261 labral tears, with all of the tears located at the relatively avascular articular junction.

It is the author’s preference to use a general anesthetic supplemented with a lumbar plexus block for postoperative analgesia as well as relaxation (11). The procedure can be performed in either the supine or the lateral position and should use both a 30° and a 70° arthroscope for a thorough assessment of the joint. Modified arthroscopic flexible instruments, extended shavers, and hip-specific instrumentation should be available.

A diagnostic arthroscopic examination of the central compartment can be done systematically not only to evaluate the labrum from anterior to posterior but also to locate possible cartilage lesions on both the acetabular and the femoral side (5). The typical cartilage lesions are adjacent to injured labrum. The acetabular notch should be evaluated and the integrity of the ligamentum teres should be assessed. This can be a source of pain as a result of impingement of the soft tissues between the femoral head and the acetabulum. In addition, severe synovitis can be found in this area. If encountered, it should be debulked or removed(Fig. 48.2). Any loose bodies should be noted and their source identified. Finally, an assessment should be made of any obvious capsular redundancy or laxity.

Many patients will have a significant synovitis associated with the labral tearing and an effort should be made to resect some of the inflamed tissue, not only for visualization of the joint but also to decrease the associated pain. It is the author’s preference to use a radio frequency (RF) probe in order to decrease the potential for bleeding and subsequent compromise of the surgical field.

The goal of the procedure should be to preserve as much tissue as is technically feasible, while resecting the degenerative or damaged portions. This is important in order to maintain the labrum’s role as a secondary joint stabilizer and to minimize the potential for arthrosis. Frayed labral tears should be debrided with the use of either motorized shavers or RF probes (Fig. 48.3). Placing absorbable suture through the defect and tying the suture through the capsule can stabilize intrasubstance labral tears. It is important to delineate the areas of abnormal tissue that are identified both on radiographs (in the form of perilabral calcifications) and on MRI/A (abnormal signal intensity) in order to thoroughly address the labral pathology. Occasionally, perilabral calcifications can be in the formative stage and these should be sought out and decompressed (Fig. 48.4).

An outcome correlated classification system of labral injuries and chondral damage has been created by Wardell et al., stage 0, as compared with normal

acetabular labrum, constitutes a contusion of the labrum with adjacent synovitis; stage I is a discrete labral free margin tear with intact articular cartilage of the acetabulum and femoral head; stage II is a labral tear with focal articular damage to the subjacent femoral head but with intact acetabular articular cartilage; stage III is a labral tear with an adjacent focal acetabular articular cartilage lesion with or without femoral head articular cartilage chondromalacia (12). In the author’s experience, this is the most common type of tear seen in those patients with cam impingement.(Fig. 48.5). Stage IV constitutes an extensive acetabular labral tear with associated diffuse arthritic articular cartilage changes in the joint. Ninety-five percent of the time the labral injury involved the anterior half of the joint. All patients who had combined anterior and lateral labral injuries had associated degenerative arthritis in the joint. This classification is loosely used to establish a general algorithm for treatment of these complex patients.

acetabular labrum, constitutes a contusion of the labrum with adjacent synovitis; stage I is a discrete labral free margin tear with intact articular cartilage of the acetabulum and femoral head; stage II is a labral tear with focal articular damage to the subjacent femoral head but with intact acetabular articular cartilage; stage III is a labral tear with an adjacent focal acetabular articular cartilage lesion with or without femoral head articular cartilage chondromalacia (12). In the author’s experience, this is the most common type of tear seen in those patients with cam impingement.(Fig. 48.5). Stage IV constitutes an extensive acetabular labral tear with associated diffuse arthritic articular cartilage changes in the joint. Ninety-five percent of the time the labral injury involved the anterior half of the joint. All patients who had combined anterior and lateral labral injuries had associated degenerative arthritis in the joint. This classification is loosely used to establish a general algorithm for treatment of these complex patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree