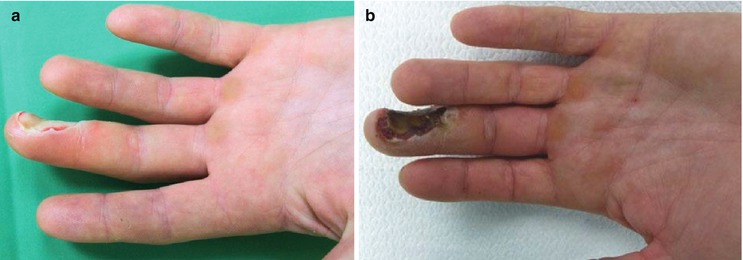

Fig. 14.1

Deep laceration wound of the hand with injury of thenar muscles

Severe bruising (tissue contusion)

Thermal destruction (Fig. 14.3)

Fig. 14.3

Entrance site of a low-voltage burn (a), after 5 days before debridement (b)

There are many classic injuries associated with certain types of accidents. Falling on the outstretched palm with hyperextension of the wrist is often the mechanism for fracturing the scaphoid.

14.1.4 Planning

Treatment planning is based on careful analysis of the initial injury and the resulting defect after surgical primary care, the lost functions, and the necessary reconstruction, including soft tissue coverage.

Surgical treatment is directed at achieving the following goals:

1.

Complete removal of infected or avital tissue

2.

Restoration of tissue perfusion

3.

Bony stabilization with minimal additional soft tissue trauma

4.

Stable, well-perfused, and aesthetically adequate soft tissue coverage

5.

Early mobilization of the limb in order to minimize post-traumatic scarring and restore function and motion of the hand

Many factors enter into the treatment plan for each individual patient, including age, education, vocation, hand dominance, expectations, and even hobbies.

14.1.5 Surgical Procedure

The surgical procedure may be divided into several steps:

14.1.5.1 Acute Care/Emergency Room Management

Review of the injury and possible additional injuries (ABC rule, exclusion of danger to life and involvement of sensory organs, especially eyes and ears)

Hemostasis of acute bleeding (by tourniquet, usually no clamping of vessels)

Reduction of bony deformities

Control of tetanus protection, if necessary booster or vaccination, antibiotic administration

Cooling of devascularized tissue (leaving intact skin bridges)

Polytraumatized patients, that is, patients with life-threatening injury to one or more organ systems, must always be judged in terms of the leading injury (“life before limb”). Treatment of hand injuries is limited to temporary stabilization of bone injuries and bleeding. For clinically unstable patients, amputations may be more useful than lengthy reconstructions.

After determining the leading injury, triage is performed and hemostasis and prevention of life-threatening blood loss is the first goal in the emergency room. Removal of a compression bandage often significantly improves the perfusion situation and enables further evaluation, including pulse status and sensibility testing.

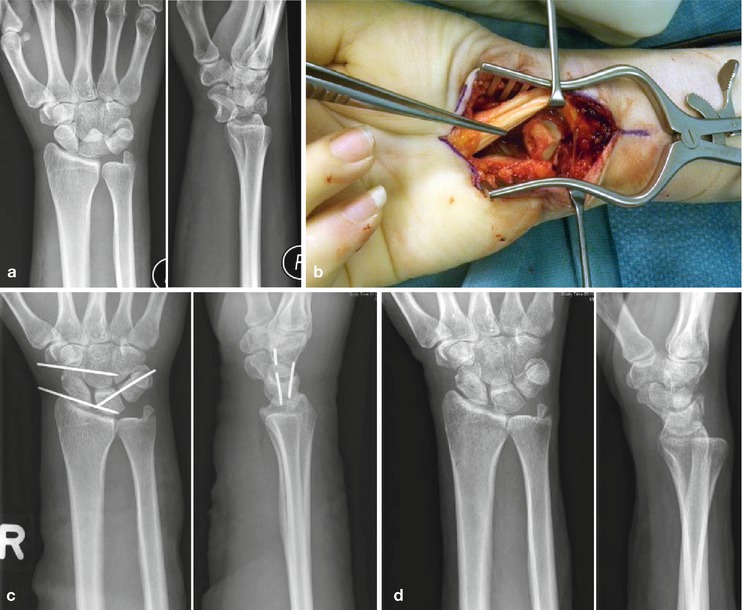

The exact medical history includes factors such as age, occupation, recreational interests, additional illnesses, medications, allergies, and other factors, such as nicotine consumption. It is always important to document the exact circumstances of the accident and mechanism, as this can significantly influence further treatment and prognosis. Radiographs of the affected limb in two planes (also amputate) should be performed (Fig. 14.4).

Fig. 14.4

Radiograph of amputate and hand

14.1.5.2 Anesthesia and Use of Tourniquet

Anesthetic requirements for hand surgery are few and simple. The patient should be free of all pain and lie quietly throughout the operation, including application of the dressing. The vast majority of patients are healthy young people for whom a wide variety of general or regional nerve block techniques are equally satisfactory.

In case of complex hand injuries or multiple amputations of finger with expected long operation times, the operation should be performed under general anesthesia, if necessary, with brachial plexus. Postoperative monitoring in the ICU should be considered.

Regular use of a pneumatic tourniquet to maintain a bloodless operation has been a major contribution to reparative hand surgery and is essential both for the identification of injured structures and to protect uninjured ones.

In most cases, one and a half hours ischemia time is sufficient for identification of injured parts, debridement, and dissection. Most of the repairs can be performed following the release of the tourniquet if necessary.

The pressure of the pneumatic tourniquet should not be above 300 mmHg on the adult upper extremity and proportionally less for children.

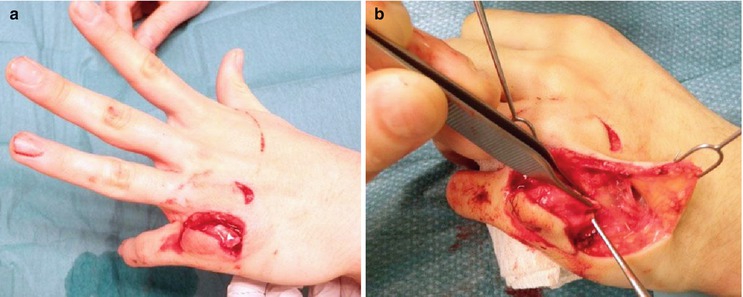

14.1.5.3 Surgical Debridement

Debridement of complex hand injuries follows several important rules

Wound excision and aggressive debridement of necrotic and ischemic tissue, especially muscle

Preservation of critical structures (nerves, tendons, and arteries)

Marking of important structures such as nerves, blood vessels and tendons for any secondary reconstructions (Fig. 14.5).

Fig. 14.5

Preoperative view of severe self-wrist cutting injury (a); View after debridement: complete transection of tendon, nerve, and vessel with defect (b)

In amputation injuries, during initial debridement, well-preserved or vascularized tissue components (spare parts, such as bones, tendons, nerves, or blood vessels) should be preserved for use in reconstruction or soft tissue coverage (fillet flap, skin grafts).

The extent of debridement in “crush injuries” is often difficult to assess. Wound assessment can be complicated, especially with closed injuries, because a significant soft tissue injury case is sometimes detected preoperatively but underestimated in many cases.

14.2 Bone and Joint Reconstruction

Fractures of the hand are the most common of all fractures. Radiographs are required in at least two planes to confirm clinical impressions and to demonstrate the extent of injury. CT scan may be necessary with fracture of the hook of the hamate or of the scaphoid.

Stabilization of bone injuries is usually performed by simple, fast, and less traumatic methods, for example, K-wires or external fixation; it is less often performed with plating.

Important strategies in the care of bony injuries are:

Fracture visualization by minimal wound enlarging, without destruction of periosteum

Maximum length preservation; bone reduction only if for the primary soft tissue closure or for bone and nerve reconstruction necessary

Accurate anatomical fracture reduction with special consideration of joint surfaces

Bridging of defects with external fixation or plate (Fig. 14.6)

Fig. 14.6

Open fracture with segmental bone loss and severe soft tissue trauma (a). The mini Hoffmann external fixation device applied for a complex proximal phalanx fracture; due to external fixation, a primary tendon repair can be achieved (b)

Complex bony reconstruction, for example, iliac crest bone graft is usually performed secondarily

Bony stabilization is recommended to enable early movement therapy. Examples include

Radius/ulna – plating (Fig. 14.7)

Fig. 14.7

Fractured radius and ulna treated with plating of both bones

Wrist – compression screw/K-wires, reconstruction of injured ligamentous structures, stabilization with K-wires

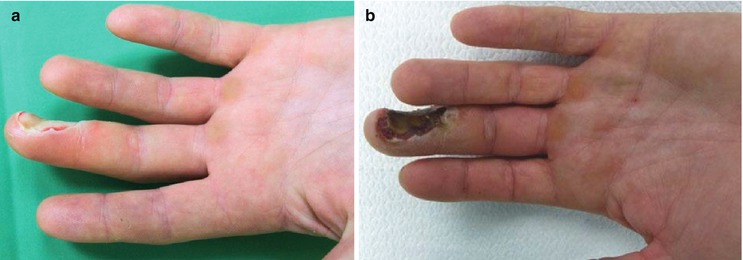

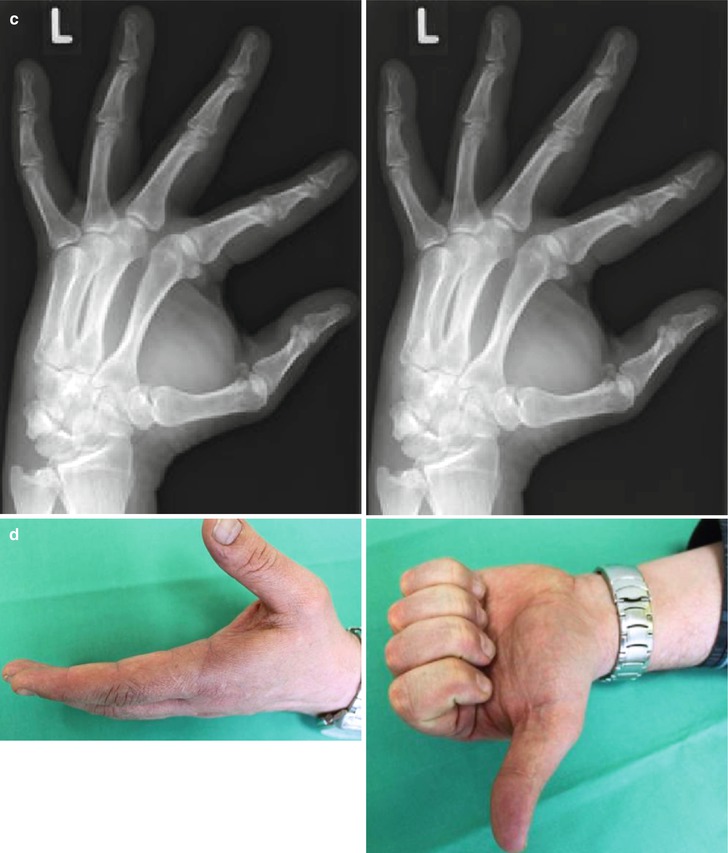

Metacarpals – mini plate fixation for early mobilization (Fig. 14.8)

Fig. 14.8

Circular saw injury of the hand with open metacarpal fractures, segmental bone loss, extensor tendon injury and dorsal soft tissue injury (a); metacarpal shaft fractures 3–5, mini plate fixation with some shortening of the metacarpal (b); repair of extensor tendon (c); radiograph preoperatively and after open reduction and internal fixation with 2.3 mm dorsal plate (d)

To exclude additional injuries of the wrist or fingers, they are moved under the imager to detect, for example, overlooked ligament injuries or dislocations.

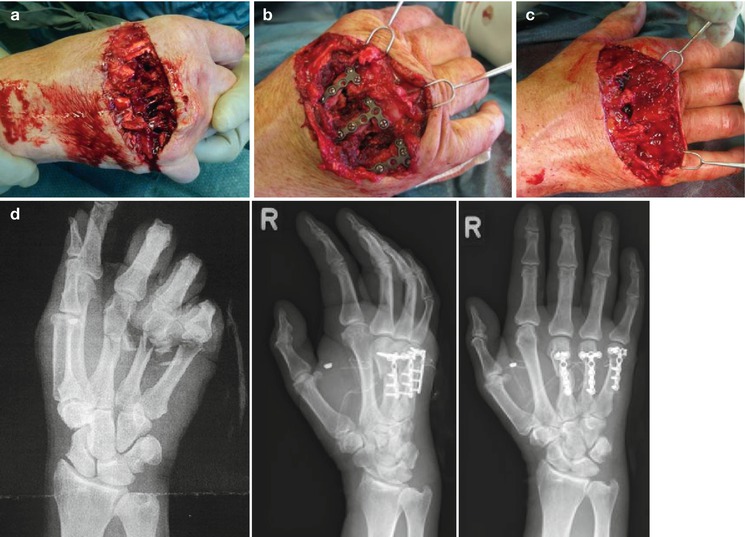

In a perilunate dislocation, open reduction and suture of carpal ligaments (especially the SL ligament) should be performed (Fig. 14.9). In joint destruction a primary fusion (arthrodesis) in appropriate function may be advisable.

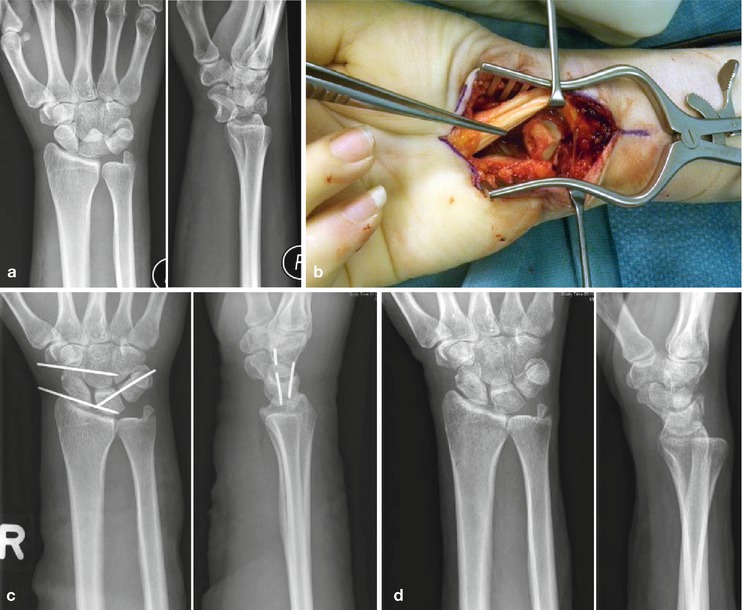

Fig. 14.9

Preoperative radiograph showing dorsal perilunate dislocation in which the lunate dislocates from its fossa and is rotated more than 90° (a); intraoperative image showing the dislocated lunate (b); after open reduction and K-wire fixation (c); after 12 weeks and K-wire removal (d)

14.3 Digital Joint Injuries

Dislocations of the metacarpophalangeal (MP) finger joints are rare. They usually result from falling on the outstretched hand or another mechanism that forces the MP joint into severe hyperextension. They are limited to the index and the small fingers.

These are classified as simple when reduction is easily accomplished and complex when soft tissue elements preclude closed manipulative reduction. After reduction, protection against recurrent injury is provided initially by splinting and then by taping the involved finger to a normal adjacent digit for 2 or 3 weeks. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, then the injury becomes a complex type of dislocation that requires an open reduction.

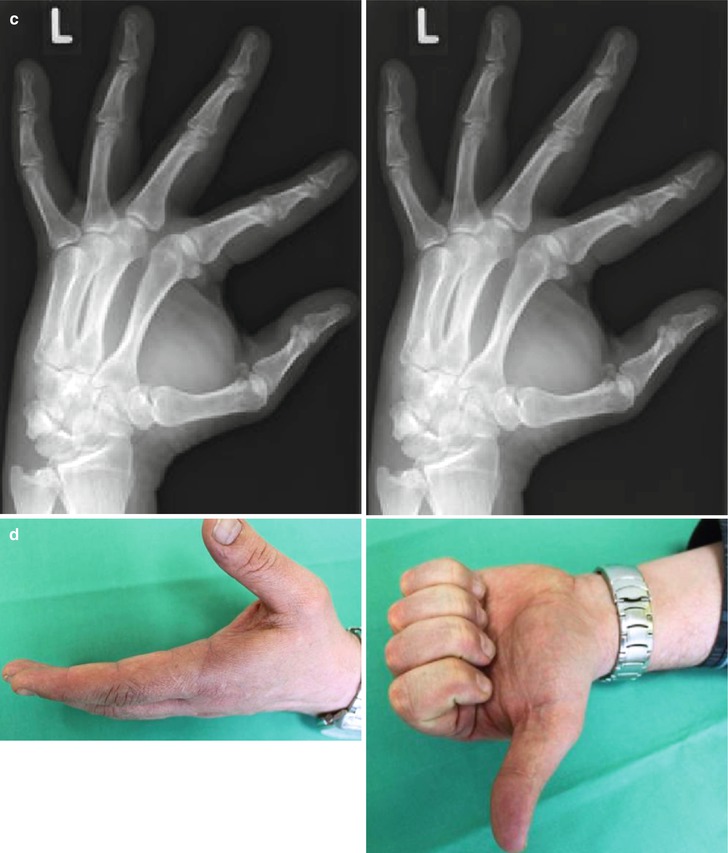

Stability and pain-free motion of proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints is extremely important to hand function. Therefore, injury to these joints warrants high priority in treatment. PIP joint dislocations are usually dorsal and result from force on the end of digit with hyperextension (Fig. 14.10).

Fig. 14.10

Open PIP joint dislocation of the middle finger, palmar plate rupture of the ring- and small finger (a); preoperative radiograph (b); radiograph after treatment with protected motion (Extension Block Splint) (c); 12 month follow-up, the patient had no pain and achieved functional range of motion (d)

PIP joint injuries that are stable with active motion can be treated by immobilization with a dorsal splint, usually in 20–30° of flexion for comfort and to rest the soft tissues. The period of immobilization ranges from as little as 3–5 days for mild hyperextension injuries to 7–14 days for dislocations and stable fracture dislocations. Duration of immobilization is individualized, depending on the extent of the injury and resultant amount of soft tissue swelling.

14.4 Tendon Suture and Reconstruction

The prognosis for tendon repairs is determined primarily by what tissues lay in contact with the repair of the tendon.

Extensor tendon injuries of the hand represent common injuries that are underestimated in many cases. If there is a delay in diagnosis and the primary injury is overlooked, deformities (e.g., buttonhole or boutonniere deformity, swan neck deformity) may have already been made. Secondary reconstruction after extensor tendon injuries is more difficult and yields worse results than primary care.

14.4.1 Zones of Extensor Tendon Injury

The dorsum of the hand, wrist, and forearm are divided into eight anatomic zones to facilitate classification and treatment of extensor tendon injuries. The most widely used classification system is that described by Verdan.

Zones 1, 3, 5, and 7 lie over the distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ), proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ), metacarpophalangeal joint (MCPJ), and wrist joint, respectively.

The even numbers are allocated to the intervening zones. The zones of the thumb differ from the finger as there are only two phalanges. They are numbered 1–5, with zones 1, 3 and 5 overlying the interphalangeal joint (IPJ), MCPJ, and wrist joint, respectively. The even numbers, 2 and 4, apply to the intervening zones.

Zone 1 (distal interphalangeal [DIP] joint)

Zone 2 (middle phalanx)

Zone 3 (proximal interphalangeal [PIP] joint)

Zone 4 (proximal phalanx)

Zone 5 (metacarpophalangeal [MCP] joint)

Zone 6 (dorsum of hand)

Zone 7 (wrist)

Zone 8 (dorsal forearm)

Extensor tendon injuries may require operative intervention, depending on the complexity of the injury and the zone of the hand involved.

Zone 1 injuries, otherwise known as mallet injuries, are often closed and treated with immobilization and conservative management where possible. Zone 2 injuries are conservatively managed with splinting. Closed Zone 3, or “boutonniere,” injuries are managed conservatively unless there is evidence of displaced avulsion fractures at the base of the middle phalanx, axial and lateral instability of the PIPJ associated with loss of active or passive extension of the joint, or failed nonoperative treatment. Open zone 3 injuries are often treated surgically unless splinting enables the tendons to come together. Zone 5 injuries are often caused by human bites and, require primary tendon repair after irrigation. Zone 6 injuries are close to the thin paratendon and thin subcutaneous tissue and require strong core-type sutures and then splinting; they should be placed in extension for 4–6 weeks. Complete lacerations to zone 4 and 6 involve surgical primary repair followed by 6 weeks of splinting in extension (Fig. 14.11).

Fig. 14.11

No active extension of the small finger due to extensor tendon injury (a); intraoperative image showing tendon injury in zone 6 (b)

Zone 8 requires multiple figure-of-eight sutures to repair the muscle bellies and static immobilization of the wrist in 45° of extension.

14.4.2 Zones of Flexor Tendon Injury

The five flexor tendon zones are modifications of Verdan’s original work, which based zone boundaries from distal to proximal on anatomic factors that influenced prognosis following flexor tendon repair. The five zones discussed below apply only to the index through small fingers; separate zone boundaries exist for the thumb flexor tendon.

Zone 1 extends from just distal to the insertion of the superficialis tendon to the site of insertion of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon (FDP).

Zone 2 is often referred to as “Bunnell’s no man’s land,” indicating the frequent occurrence of restrictive adhesion bands around lacerations in this area. Proximal to zone 2, the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendons lie superficial to the FDP tendons. Within zone 2 and at the level of the proximal third of the proximal phalanx, the FDS tendons split into two slips, collectively known as Camper chiasma. These slips then divide around the FDP tendon and reunite on the dorsal aspect of the FDP, inserting into the distal end of the middle phalanx.

Zone 3 comprises the area of the lumbrical muscles origin between the distal margin of the transverse carpal ligament and the beginning of the critical area of pulleys or first annulus. The distal palmar crease superficially marks the termination of zone III and the beginning of zone II.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree