MYLA U. QUIBEN, PT, PhD, DPT, GCS, NCS, CEEAA After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to: 1. Analyze how the aging process may affect people with lifelong functional limitations and challenges in life participation. 2. Analyze the unique challenges faced by people with chronic motor impairments such as those associated with cerebral palsy, genetic malformations, developmental disabilities, postpolio syndrome, spinal cord injury, and traumatic or acquired head injury during the aging process. 3. Evaluate this population of patients/clients with sensitivity and skill, incorporating precautions and effectiveness of interventions. 4. Provide a framework for the examination process for individuals with chronic conditions. 5. Present holistic intervention considerations for individuals with chronic motor impairments. 6. Identify gaps in knowledge and research in the management of aging individuals with chronic neuromuscular conditions. 7. Appreciate the complexity of examination, evaluation, and management of the aging patient with chronic motor impairments. The aging process typically leads to gradual physiological changes in muscle strength, flexibility, and joint mobility and changes in balance and endurance. Physical activity and a healthy lifestyle have been shown to address age-related changes by delaying the decline and deterioration; however, age-related changes such as osteoarthritis and vascular changes are still likely to occur to varying degrees despite a healthy lifestyle. Healthy but sedentary older individuals report more problems in activities of daily living (ADLs) than do those who continue to be physically active and who previously had an active lifestyle.1–3 In the realm of chronic problems in life participation, individuals who experienced the effects of polio in their younger years give clinicians an enlightening example of the chronic interaction among neurological and functional impairments, recovery, effects of aging, and health care. As a chronic condition, individuals who dealt with polio can teach therapists to reconsider and reevaluate their approach to individuals who are now experiencing activity limitations, impairments, and ineffective postures and movement. The challenges of aging with chronic body system problems or impairments are encountered by individuals who have postpolio syndrome (PPS); those who acquired CNS insult at birth (developmental disabilities including cerebral palsy [CP; see Chapter 12] and Down syndrome [see Chapter 13]); and those who acquired injury through disease or trauma sometime in the life span development process (traumatic brain injury [TBI; see Chapter 24], multiple sclerosis [MS; see Chapter 19], and spinal cord injury [SCI; see Chapter 16]). The discussion of chronic impairments brings several questions to the forefront: This chapter aims to provide a holistic view of the management of the chronic problems of individuals with nervous system impairments, with consideration given to the effects of aging and compensation over time. Movement emerges from the interaction among the individual, task, and environment,4 with several variables and degrees of freedom. Therefore physical therapists (PTs) and occupational therapists (OTs) need to examine and address multisystem impairments and contributions to movement while appreciating the changing dynamics of a highly complex movement system. With increasing life expectancy, mainly as a result of innovations in health care, a unique group of individuals with chronic conditions are subject to age-related changes. Individuals with developmental disabilities constitute a growing segment of the aging society. This is a broad topic, in part because of the many conditions that are categorized as developmental disability. According to the Administration on Developmental Disabilities and the Administration for Children and Families,5 developmental disabilities are severe, chronic functional limitations attributable to mental or physical impairments or a combination of both, that manifest before age 22 years and that are likely to continue indefinitely. These result in substantial limitations in three or more of the following areas: self-care, receptive and expressive language, learning, mobility, self-direction, capacity for independent living, and economic self-sufficiency. These individuals also have a continuous need for individually planned and coordinated services.6 The definition envelops a wide range of conditions leading to significant and lifelong disabilities. This group includes those with genetic and neurological conditions, two of the more common of which are CP (see Chapter 12) and Down syndrome (DS; see Chapter 13). The question of whether unexpected changes among people with neurodevelopmental disabilities occur as they age and how these changes compromise functioning with progressive aging is of massive importance with the emergence of a population of individuals with developmental disabilities with increased life expectancy and concurrent increase in older-age–related diseases. According to Heller7 the number of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities aged 60 years and older is projected to nearly double from 641,860 in 2000 to 1.2 million by 2030 owing to increasing life expectancy and the aging of the Baby Boomer generation. With the aging of adults with developmental and genetic disorders a new societal issue looms, as individuals with developmental disabilities have a lifelong need for external support. Much is unknown about the long-term effects of aging and maturation in adults with these conditions. Adults with several types of developmental disabilities have life expectancies similar to those of the general population, excluding adults with particular neurological conditions and with more severe cognitive deficits. Recent studies show the mean age at death ranges from the mid-50s for adults with severe disabilities or DS, to the early 70s for those with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities.8–10 Concurrent with an increased life span, some evidence exists that certain individuals with developmental disabilities have experienced an increase in age-related diseases. Of the limited information available, research has shown that aging affects certain genetic and neurologically based intellectual and developmental disabilities that may increase the risk of age-related pathologies and lead to an increased occurrence of coincident conditions.11 Of several developmental conditions, DS has been the subject of a substantial body of research. DS is known for resulting in advanced aging that includes a higher risk for Alzheimer disease and select organ dysfunctions.11–13 Evidence exists that adults with CP, considered a life span disability, lose functional abilities earlier than individuals who are able-bodied.14 For CP, evidence is also increasingly pointing to specific age-related outcomes such as the effects of deconditioning, limitations with performance reserve, and possibly a shorter life span.11 In adults with CP, secondary conditions commonly described in research primarily are related to the long-term effects on the musculoskeletal system, such as pain, degenerative joint disease, and osteoporosis.11,15,16 Secondary impairments in CP can progress subtly and may not appear until late adolescence or adulthood.15 Age-related health conditions are also seen in other genetic and neurological disorders as the affected individuals age. However, the nature of these risks lacks extensive substantiation in the literature. Overall, knowledge of adult health issues for older people with developmental disabilities is limited.7 Several reasons contribute to the lack of knowledge. Limited health care programs exist for this population, likely because this is an emerging population. Most of the existing literature is in the pediatric domain rather than dealing with age-related issues. Although these individuals were likely seen by therapists for various functional limitations throughout their lives, the professional training that health care providers have received regarding the care of these individuals has focused on early childhood and school-aged children. As a result, many adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities have difficulty accessing appropriate health care information regarding secondary conditions resulting from their specific disabilities. Moreover, in general, older individuals with developmental disabilities have more difficulty in finding, accessing, and paying for high-quality health care.7 Communication difficulties also limit the understanding of the experiences of aging adults with developmental disabilities. Evidence exists, however, showing that obesity and inactivity are more common in individuals with developmental disabilities than in the general population.17 Bazzano and colleagues17 identified several reasons for this health discrepancy, including individual and community factors, physical challenges, segregation from the community, lack of accessible fitness facilities and developmentally appropriate community programs, and cognitive deficits. Given trends of increasing survival and longevity observed among individuals with developmental disabilities, it is sensible to consider a more in-depth look at the aging process among a variety of neurodevelopmental conditions and the need for a holistic approach. Although some literature exists regarding life span changes with these disorders, particularly DS and CP, there is lack of confirming evidence for most of these conditions. Horsman and colleagues14 advocate for research on the expectations regarding aging for adults with CP, including preventive measures to lessen the effects of secondary impairments. This recommendation applies to developmental life span conditions and other chronic conditions that are subject to age-related changes that may be magnified or made worse by existing impairments and limitations. Evidence-based research is necessary to better understand the long-term effects of aging on adults with developmental and chronic conditions. The challenge then is to provide a holistic examination that involves a multisystem approach and to provide appropriate referrals as necessary to address the multiple needs of individuals with developmental disabilities. In the realm of management of chronic movement dysfunction, PPS—the late effects of polio—becomes a model case for other chronic neuromuscular conditions. There is much to learn from the complex nature of the late effects of polio and the effects of aging on an already stressed system. The cause must be briefly discussed to further understand the possible effects of aging. PPS can affect polio survivors years after recovery from the initial polio infection and is characterized by multifaceted symptoms that lead to decline in physical functioning.18 PPS manifests with progressive or new muscle weakness or decreased muscle endurance in muscles that were initially affected by the polio infection and in muscles that were seemingly unaffected; generalized fatigue; and pain.18 The exact cause of PPS remains unknown on the basis of review of the literature. Although it is not clear what exactly causes the new symptoms, there appears to be a consensus that insufficient evidence implicates the reactivation of the previous poliovirus.19 Underlying causes have been proposed in a variety of hypotheses from several authors, with aging playing a key role.20–24 The suggestion that aging contributes to PPS is supported in the literature.21,25,26 By the fifth decade of life, loss of anterior horn cells begins, and by age 60 years the loss of neurons may be as high as 50%.27 Age-related changes superimposed on the already limited motor neuron pool after polio appear to be important factors in the development of PPS. With the effects of the normal aging process, the remaining anterior horn cells are further reduced to a point at which the deficits caused by the initial insult cannot be overcome. The loss of even a few neurons from a greatly exhausted neuronal pool potentially results in a disproportionate loss of muscle function.20,28 The loss of motor neurons from aging alone may not be a considerable factor in PPS because studies20 have failed to link chronological age and the onset of new symptoms. Rather, it is the length of the interval between the onset of polio and the appearance of new symptoms that seems to be more critical. Another plausible hypothesis alludes to overuse and fatigue of the already weakened muscles as a factor in the development of new muscle weakness.19,29,30 A study by Trojan and colleagues30 provides support to this hypothesis. Their results suggest that length of time since acute polio, joint and muscle pain, physical activity, and weight gain are factors associated with PPS. Years of overuse after recovery from polio causes a metabolic failure leading to an inability to regenerate new axon sprouts. The exact cause of degeneration of axon sprouts is not known. Evidence to support this hypothesis can be inferred from muscle biopsies, electrodiagnostic tests, and clinical response to exercise.20 McComas and colleagues31 suggested that neurons that demonstrated histological recovery from the initial virus were possibly not physiologically normal and were potentially vulnerable to premature aging and failure. Other proposed hypotheses include persistence of dormant poliovirus that was reactivated by unknown mechanisms, an immune-mediated response, hormone deficiencies, and environmental contaminants.20 Another hypothesis points to the loss of anterior horn cells during the initial polio as a factor.19,21 Findings from Trojan and colleagues30 support the hypothesis that the severity of the initial motor unit involvement, seen as weakness in acute polio, is critical in predicting PPS. Individuals at greatest risk for PPS had severe attacks of paralytic polio, although individuals with milder cases also had symptoms.20 These hypotheses have not been completely examined, and currently the evidence is not strong enough to support any one possible cause. Clinically it is difficult to assume that only one factor causes symptoms. The chronicity of the disease lends weight to the possibility that more than one factor contributes to the individual’s symptoms. McNaughton and McPherson32 state that the simple descriptive labels “late problems after polio” and “of late deterioration after polio” are less limiting and do not imply a direct link with the previous polio diagnosis. Post-Polio Health International33 uses the terminology “late effects of polio and polio sequelae” as the most inclusive category. Late effects of polio and polio sequelae pertain to health problems that are a result of chronic impairments from polio and may include degenerative arthritis from overuse, bursitis, or tendinitis. A subcategory under this heading is PPS leading to decreased endurance and decreased function. Currently no definitive test exists in the literature to diagnose the late effects of polio or PPS. It remains a diagnosis of exclusion, and as such the diagnostic process for PPS is challenging and may be long. Halstead and Gawne34 identified cardinal symptoms of PPS as new or increased muscle weakness, fatigue, and muscle and joint pain with neuropathic electromyographic changes in an individual with a definite diagnosis of polio. Diagnostic electromyography (EMG) may be required or used when the muscle pattern or history is atypical. The criteria most commonly used for establishing a medical diagnosis of PPS were developed by Halstead35 and are as follows: 1. A confirmed history of paralytic polio in childhood or adolescence 2. Partial to complete muscle strength and functional recovery 3. A period of at least 15 years of neurological and functional stability 4. Onset of two or more new health problems listed in Table 35-1 TABLE 35-1 ADL, Activity of daily living. Modified from Halstead L, Wiechers D, editors: Research and clinical aspects of the late effects of poliomyelitis, White Plains, NY, 1987, March of Dimes, p 17. 5. No other medical conditions to explain these new health problems Dalakas36 identified additional inclusion criteria in the diagnosis: residual asymmetrical muscle atrophy, with weakness, areflexia, and normal sensation in at least one limb and normal sphincteric function and deterioration of function after a period of functional stability unexplained by primary or secondary condition. Several individuals who recovered from polio during the early epidemics were encouraged to exercise for years and to use heroic compensatory methods for function. An exhaustive regimen of daily stretching and strengthening, demanding compliance from individuals and their support systems, was strongly encouraged. Orthotics and assistive devices were promoted as a means toward independent mobility. The outcomes of rigorous training were individuals who adapted and compensated with their remaining capabilities. Compensations include use of muscles at high levels of their capacity, substitution of stronger muscles with increased energy expenditure for the task, use of ligaments for stability with resulting hypermobility, and malalignment of the trunk and limbs. With the late effects of polio or a diagnosis of PPS, many of these individuals may have extreme difficulty dealing with these new problems because of the attitude of “working hard” to reeducate weakened muscles and compensate for loss of function after the initial diagnosis.37–40 The new symptoms of PPS, which limits their motor function and likely impairs established personal and societal roles, require that they not work hard or overexert themselves. These two approaches are contradictory and can leave an individual frustrated and confused over therapeutic recommendations. For persons with SCI and TBI, a trend is seen toward increasing awareness on the effects of aging on the functional status of this group. Owing to medical advances, patients are now living 20 to 50 years past their time of injury. Numerous studies have been done describing quality-of-life issues for people with TBI; however, those studies seldom look specifically at changes in functional levels or what can be done to ameliorate the declines.41–43 McColl and colleagues,44 studying the impact of aging on people after SCI, have identified major categories of problems related to aging, such as musculoskeletal problems and joint, sensory, and connective tissue changes; chronic urinary tract infections; heart, respiratory, and other chronic diseases; secondary complications of the initial lesions, such as syringomyelia; and problems related to social and cultural acceptance and access or barriers. Evidence on specific age-related changes is presented in the section on examination. Decreases in perceived health status and in functional abilities with increases in additional assistance for ADLs have been documented for aging individuals with SCI.45–49 In a study of 150 people aging with an SCI, nearly 25% reported decreases in the ability to perform functional activities that they had been able to handle after the acute rehabilitation phase. The subjects who reported decreases in functional ability were generally older (45 years compared with 36 years) and had longer postinjury periods (18 versus 11 years). The most common symptoms reported by the individuals with decreases in functional status were related to fatigue, pain, and muscle weakness. The ADLs reported to be more difficult were transfers, bathing, and dressing. To maintain their functional levels, those with declines in functional ability reported needing additional equipment.45 The need for further assistance with ADLs was echoed in a study by Gerhart and colleagues of individuals with SCI 20 years after the initial injury.46 The study showed that 22% of the subjects reported an increased need for support with ADLs. Compared with a general group of nondisabled men and women aged 75 to 84 years in which 78% of the men and 64% of women did not need help with ADLs, the population of persons with SCI needed increasing support to remain independent, and the need for help occurred at a younger age. On average, those with quadriplegia required more help with ADLs around the age of 49 years, whereas those with paraplegia were able to maintain their functional level until age 54 years. The groups showing functional decreases reported greater fatigue, increased muscle weakness, pain, stiffness, and weight gain.46 Other studies support the findings that 5, 10, and 15 years after the initial SCI, an association with the need for additional help with increasing age existed.47 Liem and colleagues,48 referencing an international data set of people with SCI, investigated a subset of 352 people at least 20 years after their injury. Thirty-two percent of the subjects reported needing increased help with transfers and housework compared with their functional abilities at acute hospital discharge. With increasing age, women had a higher incidence of reported musculoskeletal impairments, which may have been related to biomechanical differences between men and women (e.g., 40% lower upper body strength). In addition to the need for ADL support, neurogenic bowel and bladder symptoms also worsen with age in some people with SCIs. With changes in general health status, polypharmacy, decreased activity, and poor nutritional patterns, bowel problems (particularly constipation) become more of an issue. Although constipation seems like a minor issue relative to paralysis, those with SCIs report significant abdominal distention and pain, an increased incidence of perineal and sacral skin breakdown, and in some cases autonomic dysreflexia. In addition to the discomfort of chronic bowel dysfunctions, the required bowel care programs may take more time, which can lead to increased psychosocial issues associated with anxiety about bowel accidents in social and work situations and may take time away from social activities for both the person with an SCI and the caregiver. For those with continuing bowel problems that interfere with life and work activities, a colostomy may be an option that increases independence from caregiver support during the bowel program.50 Another complicating factor related to bowel dysfunction is the typical treatment for pain complaints. Because the origin of pain is often illusive, the most common treatment involves oral medications rather than referrals for therapeutic interventions. Pain medications, especially opioids, increase gastrointestinal difficulties in nondisabled populations,51 and the problem for patients with SCI is compounded. Charlifue and colleagues,52 drawing on the National Spinal Cord Injury Database of 7981 individuals with SCIs that occurred from 1973 to 1998, found a slight decrease in perceived health status the longer one lived after SCI. Evidence was also found that those injured later in life had a higher number of rehospitalizations after injury than those injured at a younger age. Despite palpable problems with the statistical issues within the sample, the study clearly indicated that the best predictor of a complication is a previous history of that complication. On the basis of their results, Charlifue and colleagues52 suggest that prevention of complications is the best approach to improve quality of health and quality of life for people aging with SCI. Individuals with TBI are often neglected by professional health care and insurance providers after the acute rehabilitation period. According to Levin,53 before 1980, individuals with brain injuries were considered “dead on arrival.” Persons who would have died from the TBI several decades ago are now living into old age and are coping with the changes caused by the aging process superimposed on their physical limitations and cognitive problems. Of great concern is the possible relationship between a history of brain injury and increased cognitive changes along the dementia continuum.54 Cognitive decline in the nondisabled population is a problem, but the additive effect for a person with a previous TBI may seriously impair the person’s coping mechanisms when dealing with his or her own health and self-care needs.55 Extensive work has been done on rehabilitation programs and quality-of-life issues related to head injury and, to a lesser extent, cerebral vascular accidents.56 (See Chapters 23 and 24 for interventions for head injury and hemiplegia.) Unfortunately, the focus of rehabilitation after a TBI has been on the acute and rehabilitation stages of treatment and not the chronic problems that follow this group of patients into their older years. As with other chronic conditions, few patients see a therapist after they are discharged from rehabilitation unless they have new acute events such as musculoskeletal problems or a medical condition that causes a change in functional status. Although TBI is a lifetime disability, little attention has been paid to the needs of aging persons with a TBI who may have recurring needs for physical and cognitive rehabilitation and retraining over the life span. Individuals who sustain a TBI in the older years will likely have different needs from those injured at a younger age. In a study on the effect of age on functional outcome in mild TBI, Mosenthal and colleagues57 found that those injured later in life (after age 60) had longer inpatient rehabilitation periods and lagged behind younger patients in functional status at the point of discharge; however, similar to the younger individuals who sustained a head injury, the over-60 individuals showed measurable improvement during the 6-month study period. Therefore, aggressive management of older patients with TBI is recommended, and older patients may require continuing management owing to the overlying issues of the aging process.57 This is echoed in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus document on the treatment of people with TBI, which suggests that specialized interdisciplinary treatment programs need to be put in place to deal with the medical, rehabilitation, family, and social needs of people with TBIs who are over the age of 65 years. The document also concludes that access to and funding for long-term rehabilitation is necessary to meet long-term needs; however, it recognizes that changes in payment methods by private insurance and public programs may jeopardize the recommendations.58 Although the authors of the NIH document recognize the need to deal with the aging processes associated with TBI, there continues to be a lack of services and trained professionals available, especially at the community level.59 As with the SCI population, work is now being done to investigate the relationships among TBI, aging, and health. Breed and colleagues60 found that older individuals with TBI were more likely than their age-matched nondisabled peers to report metabolic, endocrine, sleep, pain, muscular, or neurological and psychiatric problems. Their findings support those of Hibbard and colleagues61 and Beetar and colleagues,62 which suggest that medical personnel need to be prepared to treat a broad range of health issues in the aging TBI population. Fewer of the studies on long-term outcomes and issues in TBI extend to the 10- and 15-year postinjury periods that have been examined for patients with SCIs. In studies 5 years after the initial TBI, improvements in physical and social functions were noted in most areas for at least the first 2 years after injury, with the exception that those with a history of alcohol or drug abuse did less well. One could assume that continued abuse of alcohol or drugs would bode ill for individuals aging with a TBI.63 In one study of 946 children and adolescents who sustained a TBI, Strauss and colleagues64 found that patients with severe and permanent mobility and feeding deficits had higher mortality rates, with a 66% chance of surviving to age 50 years. In contrast, survivors with fair or good mobility had a life expectancy only 3 years shorter than that of the general population. However, because both severely and mildly injured individuals with a TBI can live well into and beyond their 50s, the impact of aging on the physical and cognitive deficits must be dealt with assertively to prevent superimposed disability. Estimates of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services indicate that 40 to 54 million Americans have some type of chronic condition or disability.65,66 Conditions are diverse and may be related to trauma or chronic conditions such as MS.66 Trends of increasing survival and longevity are now being observed among individuals with chronic conditions as they experience aging processes. It is timely to consider how to manage individuals with chronic impairments. Examination of individuals with chronic impairments and disabilities is challenging to say the least. Not only are the impairments and functional limitations diverse, but the combinations of these impairments and limitations are many and unique to each individual owing to societal, personal health, environmental, and psychological considerations. Moreover, the effects of aging will likely affect individuals differently depending on existing impairments, functional limitations, current health status, and each individual’s attitude toward health and maintaining their functional status and lifestyle. This entails a more thorough, methodical, multisystem examination with a meticulous health interview and wellness model (see Chapter 2).

Management of chronic impairments in individuals with nervous system conditions

What is the course of age-related medical conditions common in individuals with chronic impairments?

What is the course of age-related medical conditions common in individuals with chronic impairments?

Do age-related conditions vary among the developmental or genetic diseases or among conditions occurring at one point during the life span?

Do age-related conditions vary among the developmental or genetic diseases or among conditions occurring at one point during the life span?

What are the prevalence and/or incidence of secondary conditions in individuals with chronic impairments?

What are the prevalence and/or incidence of secondary conditions in individuals with chronic impairments?

Have specific treatment protocols for health provision for this population been identified?

Have specific treatment protocols for health provision for this population been identified?

What is the state of dissemination of information related to aging and health to people affected by these conditions?

What is the state of dissemination of information related to aging and health to people affected by these conditions?

How has the effect of aging with chronic body system problems changed the ability of these individuals to participate in life as well as their perceived quality of life?

How has the effect of aging with chronic body system problems changed the ability of these individuals to participate in life as well as their perceived quality of life?

Diagnoses with underlying chronic consequences

Developmental conditions

Neurological conditions acquired in the life span: spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, postpolio syndrome

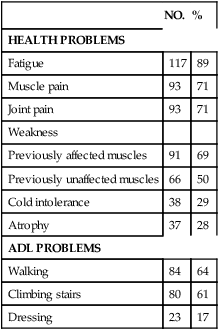

NO.

%

HEALTH PROBLEMS

Fatigue

117

89

Muscle pain

93

71

Joint pain

93

71

Weakness

Previously affected muscles

91

69

Previously unaffected muscles

66

50

Cold intolerance

38

29

Atrophy

37

28

ADL PROBLEMS

Walking

84

64

Climbing stairs

80

61

Dressing

23

17

Spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury

Examination of individuals with chronic impairments

Management of chronic impairments in individuals with nervous system conditions

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree