Chapter 130 Management of Bone Defects in Revision Total Knee Arthroscopy

Augments, Structural and Impaction Grafts, and Cones

Background

Reconstruction of large bony defects in the femur and tibia during revision knee replacement remains a challenging clinical problem. Smaller bone defects have been traditionally and effectively treated with limited quantities of morselized cancellous bone graft,3,27 cement augmented with screw fixation,1,11,28,29 or modular augments attached to revision prosthetic implants.4,14 Large or massive bone defects require more extensive reconstructive efforts and have been managed traditionally with the use of large structural allografts,* impaction bone grafting techniques with or without mesh augmentation,17,32,33,36 fabrication of custom prosthetic components,8 or specialized hinged knee components.15 Despite the multitude of utilized treatment methods, the best reconstructive technique for bone defects during revision knee replacement has not been clearly determined.8

Bone Loss Assessment and Classification

A common system of categorizing bone defects in revision knee arthroplasty is the Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute Bone Defect Classification.8 This system permits communication and comparison of knees between different institutions and also allows preoperative and postoperative classification and management recommendations for specific bone defect severities. In this bone defect classification, type 1 defects describe only minor and contained cancellous bony defects within either tibial plateau, type 2A defects include moderate to severe cancellous and/or cortical bone defects of only one tibial plateau, type 2B defects consist of moderate to severe cancellous bone defects of both tibial plateaus and/or segmental cortical defects of one tibial plateau, and type 3 defects describe combined cavitary and segmental bone loss in both tibial plateaus.

Reconstruction With Cement and Screws

Cement used as a reconstructive augment has the attraction of being simple, inexpensive, and efficient, as the revision knee arthroplasty is already utilizing the material for fixation in most instances. This reconstruction method is typically indicated for smaller contained defects measuring less than 5 mm in depth,1,11 although some authors have advocated its use in larger defects with excellent clinical results.28,29 When cement is used for defects in revision knee arthroplasty, augmentation with bone screws is typically recommended to enhance the biomechanical properties of the construct (Fig. 130-1). In addition, if the patient is young and active, it may be more advantageous to utilize morselized allograft to restore bone stock in these types of defects.

Clinical Results

Satisfactory midterm results have been reported with the use of screws and cement for bone defects in TKA. Ritter and associates28 reported on 57 TKRs with large (9 ± 5 mm) medial tibial defects reconstructed with screws and cement at an average of 6.1 years’ follow-up.28 Although nonprogressive radiolucent lines were common and were seen in 27%, no cases of tibial component loosening, component failure, or cement failure were reported. In a subsequent report by the same authors, 125 TKAs that utilized screws and cement to fill large medial tibial defects secondary to severe varus deformities were reported at a mean of 7.9 years’ follow-up.29 The authors reported two failures that occurred as the result of medial tibial collapse at 5 and 10 years, respectively, but no other failure or loosening was observed in the remainder of the cohort. However, this was a series of primary knee arthroplasties without the typical stem extensions used in revision knee arthroplasty to augment fixation and prevent medial collapse in the setting of bone deficiency and suboptimal bone quality. Therefore, in smaller and contained defects such as those encountered in revision knee arthroplasty, particularly in older or less active patients, the use of screws and cement is a viable and successful method of reconstruction that is inexpensive, relatively simple, and efficient.

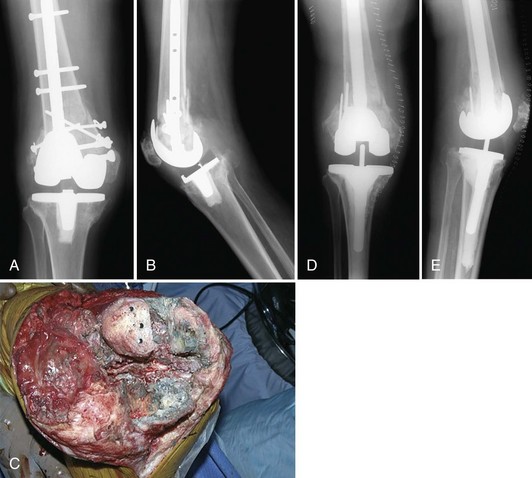

Reconstruction With Morselized Allograft

Bone loss in revision knee arthroplasty can be treated reliably and successfully with morselized cancellous allograft and has an established clinical track record.* This method typically is reserved for contained defects (Fig. 130-2) and is particularly attractive for younger patients, in whom restoration of deficient bone stock is a priority given the potential for future reconstructive surgeries. Biologically, morselized cancellous allograft appears to incorporate similarly to cancellous autograft, albeit at a much slower rate. It is also beneficial to have a well-vascularized recipient bed to facilitate incorporation of the allograft bone; if a highly sclerotic defect is encountered, it may be beneficial to burr away the sclerotic bone to underlying cancellous and vascular bone, or conversely to use another reconstruction method such as a block augment. Furthermore, if the defect is large and segmental, although some authors have reported adequate results with impaction allografting,17,18 reconstruction with more robust structural augments such as metal blocks, bulk allograft, or metaphyseal porous metal cones typically will produce more biomechanically stable constructs.

Surgical Technique

As with all reconstructive techniques, the surgical technique of utilizing morselized allograft to fill contained defects requires meticulous débridement of the defect with careful attention to removal of all fibrous tissue. Careful attention is paid to preparation of a vascular bed for allograft incorporation to host bone and long-term bone reconstitution. Once the defect is adequately débrided, prepared, and confirmed to be contained with supporting peripheral structures, the morselized allograft can be inserted into the defect. It is also preferential to grind up any larger pieces into a fine morselized consistency to facilitate the development of biologic and structural properties. It is helpful to place an adequately sized reamer or trial stem into the medullary canal to impact the morselized allograft material around the reamer; this facilitates compaction of the graft to optimize its ability to provide structural support (see Fig. 130-2C and D). Once this is complete, the reamer is removed, and the final implant is inserted with an intramedullary stem for supplemental support.

Clinical Results

Midterm results are available for the technique of impaction allograft reconstruction in revision total knee arthroplasty. Lotke and associates18 prospectively studied the midterm results of 48 consecutive revision TKAs with substantial bone loss treated with impaction allograft. At an average follow-up of 3.8 years, no mechanical failures of the revisions were reported, and all radiographs demonstrated incorporation and remodeling of the bone graft. Six complications were reported among the 42 revisions available for follow-up (14%): 2 periprosthetic fractures, 1 early infection salvaged with irrigation and antibiotics, 1 late infection resulting in fusion, and 2 patellar clunk syndromes. Although the authors concede that the technique is time consuming and technically demanding, they advocate impaction grafting for bone loss in revision TKA.18 Whiteside and colleagues37 reported on 63 patients who underwent revision knee arthroplasty using morselized cancellous allograft to fill large femoral and/or tibial defects. Firm seating of the components on a rim of viable bone and rigid fixation with a medullary stem were achieved in all cases. Fourteen reoperations occurred, and a biopsy specimen taken from the central portion of the allograft revealed evidence of active new bone formation. Evidence of healing, bone maturation, and formation of trabeculae was observed on all radiographs at 1-year follow-up. Two patients in this series required revision surgery for aseptic loosening, and the authors believed that both had greatly improved bone stock, so new implants could be applied with minor additional grafting.37

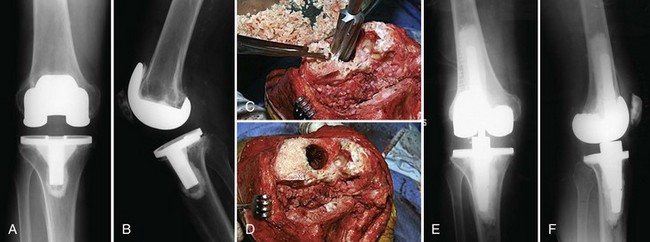

Reconstruction With Bulk Allograft

Bulk allograft has been used frequently to reconstruct large bone defects with the intention of providing mechanical support and reconstituting bone, which certainly are considered advantages of this technique. Bulk allograft is typically indicated for defects that are larger than 1.5 cm in depth and that exceed the dimensions of typical metal block augments accompanying most revision total knee systems (Fig. 130-3). The advantage of bulk allograft is the potential for bone reconstitution, particularly in young patients, for whom this goal is of great importance with the likelihood of multiple future surgeries and reconstructions. Potential drawbacks include the potential for graft resorption, collapse, and graft–host nonunion. Patient factors such as health status, physiologic age, bone quality, and activity must be weighed heavily when use of this reconstructive technique over other reconstruction strategies such as porous metal cones is considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree