A Guidelines on when to refer These tables were created by Brenda Eng, ARNP (see page ii) to help with these important decisions (2014).

Managing the Family

Skill in dealing with the parents and family is essential in providing optimum care for the child. This requires professional competence, patience, and empathy for child and family. Dealing with parents is often the area of greatest difficulty for the orthopedic resident. Developing appreciation, sensitivity, and skill in communicating with parents and the ability to calm their anxieties are essential skills in dealing effectively with the child’s problem.

Child

The child’s overall well-being is the primary objective of management. Doing what is best for the child requires respect for the inherent value of childhood as an important time of life. Childhood is more than just a preparatory period of life; it has intrinsic value [B]. Moreover, unnecessary interference with the child’s life deprives the child of important life experiences. This concept is especially important in pediatric orthopedics, where the physician often deals with chronic disease; “medicalization” of childhood is a serious risk. We may create what is referred to as the vulnerable child syndrome. These children are often harmed by unnecessary restrictions. Some philosophical and practical guidelines are given here:

B Play is the occupation of the child Childhood is the time for varied experiences and has intrinsic value.

Resist the pressure to treat the child

simply to satisfy the parents or just to “do something.” This is harmful to the child, disruptive to the family, expensive for society, and poor medical practice.

Order treatment only when intervention is both necessary and effective

In the past, treatment was commonly prescribed for conditions that resolve spontaneously, such as intoeing, flexible flatfeet, and physiological bowlegs. Observational management, a policy of monitoring the child’s condition with minimum intervention, provides optimum care for a large percentage of pediatric orthopedic problems. It is least disruptive to the child’s and family’s life and generates a reputation of honesty and competence for the physician.

Limit the child’s activity only after thoughtful consideration

Play is the primary occupation of the child. Unnecessary restriction denies the child play experiences vital to enjoying childhood and developing critical skills. In some situations, the physician may need to curb the parents’ tendency to overprotect the child. It may be in the child’s best interest to risk injury rather than to have long-term constraints on natural activity [A].

A Integrate treatment with play Encourage families to have their children participate in physically active play during treatment. These pictures were taken by a mother who achieved this goal.

Avoid medicalization of the handicapped child

Overtreatment can further limit the child and overwhelm the family. Excessive numbers of physician’s visits, operations, therapies, braces, and other treatments will result in a large share of the child’s life being expended on treatment that may provide little or no benefit.

Before considering any treatment, consider the child as a whole

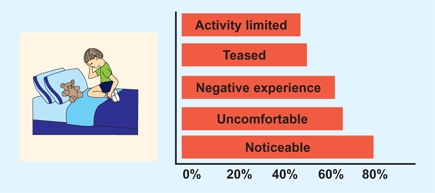

Treatment methods readily prescribed for children would never be accepted by an adult [B]. Orthopedic treatment can be damaging to the individual’s self-image [C] and be uncomfortable or embarrassing for the child [D]. Make certain that the anticipated benefits of treatment exceed the harmful psychological, social, and physical effects on the child.

B Child’s treatment may be unacceptable for adults Treatment that has been commonly prescribed for children, such as twister cables for intoeing girls or Perthes disease braces for boys, would never be accepted by an adult patient.

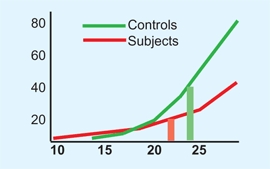

C Orthopedic treatments and self-image Adults who wore corrective devices as children (red) showed a significantly lowered self-image compared to controls (green). From Driano, Staheli, and Staheli (1988).

D Recollections Percentage of adults recalling experience about wearing orthopedic devices during childhood. From Driano, Staheli, and Staheli (1998).

Care of the child requires the highest medical standard

The results of treating a child, whether good or bad, may remain with the patient for 70 years or more.

Parents

Dealing with parents is an essential part of a pediatric practice [E]. Each family has certain rights, such as privacy, that must be respected, as well as differing needs and values.

E Parent discussions Take the families’ concerns seriously. Allow enough time to explain the disease and treatment options thoroughly.

Family coping ability

should be respected. Respect the family’s resources concerning time, energy, and money. A handicapped child adds stress and complexity for any family. Balance the treatment plan and the family’s resources. Consider the well-being of the other children and the health of the marriage; if these are marginal, it may be prudent to order only essential treatment. At different times during management, encourage questions and discuss progress with the family. Being sensitive to the coping ability of the family is part of the physician’s responsibility. Demanding more than the family can handle results in noncompliance that may be more the fault of the physician than the family.

Informed consent

should be part of all management, whether surgical or not. The family has the right to know the pros and cons of the management alternatives. The physician’s influence is greater with adults as parents than as patients. Most parents are very sensitive to the possibility that the child’s current condition may cause some disability in adult life. Certain words, such as “arthritis,” “crippled,” and “pain,” have a powerful effect on parents and should be used with caution. For example, in the past, many rotational osteotomies were performed to correct femoral antetorsion under the assumption that the procedure would prevent arthritis of the hip. Although the prophylactic value of the procedure was uncertain, parents readily gave their consent under the presumed threat of arthritis [A]. Several recent studies have shown no relationship between femoral antetorsion and arthritis.

A Complications of rotational osteotomy This patient underwent an osteotomy for correction of femoral antetorsion. He developed a streptococcal wound infection. This was further complicated by failure of the fixation, nonunion, osteomyelitis, and limb shortening. He had 13 operations to manage complications.

Support and reassurance

should be provided for patients and parents. In managing common resolving problems such as intoeing [B], reassurance is the main treatment. With more serious problems, reassurance may take the form of providing information that dispels the parents’ fears about the future. In critical conditions, reassurance consists of assuring the family that you will support them throughout the disease. The process of providing effective support and reassurance involves several steps:

B Femoral antetorsion improves with growth This is considered a variation of normal that requires no treatment.

Make certain that you understand the family’s concerns

and take these concerns seriously.

Conduct a thorough evaluation of the child

Pay attention to the family’s specific concerns. For example, if they are anxious about the way the child runs, be certain that you observe the child running in the hallway.

Provide information about the condition,

especially the natural history. Make copies of appropriate pages of what families should know for the family to take home and show other family members.

Offer to follow the problem in the future

Not all positional deformities resolve with time. Offer to see the child again if the family has additional concerns. If the family is obviously apprehensive, or there is someone in the family who is the major source of concerns, such as the grandmother, it may be necessary to provide reassurance repeatedly. For example, suggest that the grandmother accompany the child during the next visit.

If the family is still unconvinced, suggest a consultation

An offer to refer the child usually increases the family’s confidence in the physician. Be certain to communicate to the consultant the family’s need for reassurance and not that you are recommending some treatment.

Avoid submitting to family pressure for treatment that is not medically indicated

Performing unnecessary or ineffective procedures because of family pressure is never appropriate.

Procedures

are a source of family stress. Whether the family should be present during procedures, such as joint aspiration, should be managed individually. Some parents prefer not to be present; others insist on being with the child. Whenever possible, give the family a choice. Be aware that if the parents are present, one of them (usually the father) may feel ill or dizzy and need to lie down. More often, a parent can help calm the child [C and D]. Moreover, the presence of parents helps to prevent feelings of abandonment in the child. In summary, even though the parents’ presence may add a complicating factor for the physician, it may be of benefit to the child.

C Procedures are less stressful in a supportive environment Often the mother is best able to comfort the child.

D Supportive measures during casting Ongoing support of the child during simple procedures calms and quiets the child.

Litigious problems

are fortunately less common in pediatrics compared with other orthopedic subspecialities. However, the legal exposure period for the physician is much longer, because the statute of limitations usually starts at the age of majority. Medical competence, attention to detail, and good rapport with the family are the best protective measures. Additional measures include complete records, generous use of consultants, and avoidance of nonstandard treatments. If an unusual or tragic incident occurs, document the circumstances honestly and thoroughly. Be especially attentive to the family at this time and respond quickly to their concerns.

Religious beliefs

may affect the physician’s management. Religious beliefs should be respected to the extent that they do not compromise the child’s treatment [A]. Discuss the parents’ beliefs and concerns openly. Issues regarding blood replacement are common. Alternatives are possible, so do not victimize the child by taking a rigid position against the family. With planning, careful technique, hypotensive anesthesia, and staging if necessary, nearly all orthopedic procedures can be managed without blood replacement. Some families will want a period of time for prayer before giving consent for an operative procedure. Unless time is critical, a negotiated delay is appropriate. Establish a time limit and determine some objective outcome measures in advance.

A Religious beliefs Respect the family’s right to make or at least influence medical decisions that do not compromise the child’s treatment.

Family values

should be incorporated into the management plan. For some medical conditions, management indications are unclear or controversial. Inform the family of the situation and discuss the choices openly so that the management is consistent with the family’s values [B]. Family feelings about operative procedures, bracing, therapy, and other treatment methods vary considerably. The family’s feelings and values should be respected but should not supersede the delivery of optimal medical care. Performing an operation that is medically not indicated because of family insistence is not appropriate.

B Family’s values Incorporate these values in planning management.

Difficult families

may tax the physician’s ability to deal with the parents’ reaction to their child’s illness. The parents may become overprotective or, conversely, may abandon the child. Some parents become abusive toward the physician and staff. Be sure that the parents’ behavior does not adversely affect your management of the child. Be understanding but firm, and when appropriate, support abused staff members. Write a note in the chart summarizing the parents’ behavior.

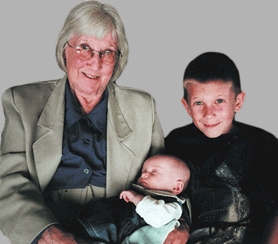

Grandparents

often accompany the child to the clinic [C]. Grandmothers are often concerned about infants’ flatfeet, intoeing, or bowlegs. In the grandmother’s child-rearing era, positional problems were poorly understood and routinely treated. Overcoming such misconceptions requires a willingness to respectfully explain the reasons for current management.

C Grandparents in the clinic This grandmother is very well informed and an asset in helping the parents deal with their children’s problems.

Unorthodox methods

of care by nonphysician practitioners are often considered by parents. Such practitioners usually prescribe treatment, and the treatment often continues over a long period of time. By current standards, such treatments are generally unnecessary and ineffective. Moreover, the treatment may delay necessary treatment. Avoid criticism when discussing these “treatments” with the family; instead, focus on parent education. This is much more effective than criticism. If the parents insist on unorthodox treatment, suggest an objective outcome measure and reevaluate the child later. If appropriate management cannot wait, use a more aggressive approach. Start with the basic facts, obtaining consultations for reinforcement if necessary.

Society

The physician’s responsibility to society is seldom addressed. Physicians do have the responsibility to keep health care costs to a minimum by avoiding inappropriate management. Physicians can also choose the least expensive alternatives among equivalent management methods [D].

D Home traction Home treatment programs provide cost-effective and convenient management.

Shoes

For a long time, shoe modifications were a traditional treatment for infants and children for a wide variety of pathological and physiological problems. Because shoe modifications were usually prescribed for otherwise spontaneously resolving conditions, resolution was falsely attributed to the shoe. This led to the concept of the “corrective shoe.” Recently, database studies have consistently shown that natural history, rather than shoe modification, was responsible for the improvement [A]. We now know that the term “corrective shoe” is a misnomer. Barefooted people have been shown to have feet that are stronger, more flexible, and less deformed than those wearing shoes [B and D]. The feet of infants and children do not require support and do best with freedom of movement without shoes.

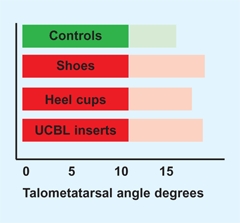

A Effect of shoe modifications in flatfeet This prospective, controlled study compared arch development with various treatments. No difference was found. Talometatarsal angles before (light shade) and after treatment (dark shade). From Wenger et al. (1989).

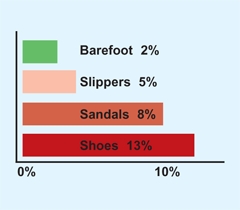

B Correlation of shoe wearing on incidence of flatfoot in adults In a survey of adults, the percentage with flatfeet was related to shoewear during childhood. Note that flatfeet were least common among barefoot children. From Roe and Joseph (1992).

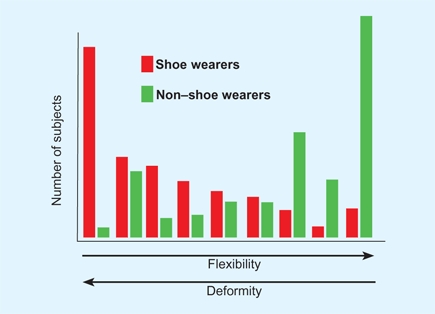

D Effect of shoe wearing on the incidence of deformity and flexibility in adults In a survey of Chinese adults, those who wore shoes had more deformity and less flexibility than nonshoe wearers. From Simfook and Hodgson (1958).

Shoe Selection

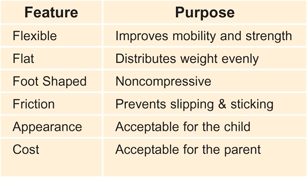

The selection of shoes should be the same as for other clothing. The shoe should protect the foot from injury and cold and be acceptable in appearance. The best shoes are those that interfere least with function and simulate the barefoot state [E]. High-top shoes are necessary in the toddler to keep the shoes on the feet. Proper fit is desirable, not to promote support but to avoid falls and compression of the toes. Falls are more common if the shoes are too long or have sole material that is slippery or sticky.

E Characteristics of a good shoe The best shoes are those that allow normal function of the foot.

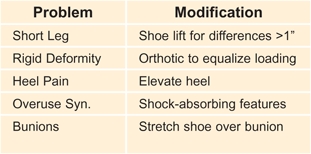

Useful Modifications

Shock-absorbing footwear may be helpful for the adolescent in reducing the incidence of overuse syndromes [C]. Some shoe modifications are helpful [F]. These are not for correction but to improve function or provide comfort. Shoe lifts may be useful if leg length difference exceeds 2.5 cm. Orthotics are effective in evenly distributing loading on the sole of the foot.

C Cushioned shoes Shoes have cushioned heels and soles (arrow) that may reduce the incidence of overuse syndromes.

F Useful shoe modifications These modifications are useful to improve the mechanics of load bearing.

Chronic Regional Pain Syndromes

Included in this category of syndromes are reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD) or reflex neurovascular dystrophy (RND), idiopathic pain syndrome, and fibromyalgia.

Scope

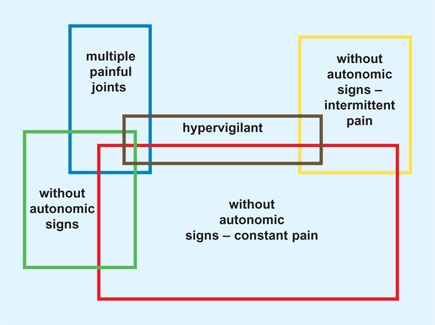

These pain syndromes are varied and may be associated with autonomic signs [A]. The patients typically present features of disability out of proportion to the trauma history or clinical findings. These patients are often seen first by the orthopedist because the pain is musculoskeletal and frequently follows minor injury.

A Overlap of chronic regional pain syndromes Note the varied patterns. From Sherry (2000).

Diagnosis

The patients present with a wide variety of clinical features [B]. Usually the evaluation elicits a sense of disparity. The pain or disability is exaggerated beyond any signs of underlying disease. The findings may show dynamic or fixed deformity [C], considerable variations from autonomic features [D].

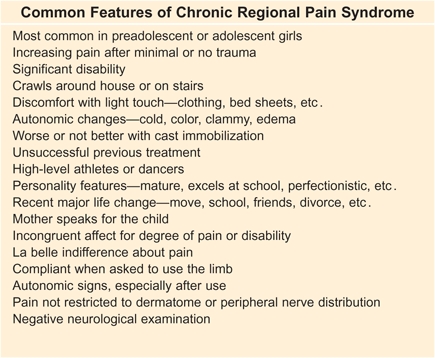

B Common features of chronic regional pain syndrome Based on Sherry (2000).

C Severe fixed deformity from RSD This 15-year-old girl developed a fixed equinovarus deformity of the foot (red arrow) over a period of many months. Correction required soft tissue releases and casting (yellow arrow).

D Autonomic features of right foot Note the discoloration and swelling of the leg and foot (red arrow) and increased uptake on bone scan (blue arrow).

Management

These patients are difficult to manage. The psychological or functional underlying problem is often clear, but the family will likely be offended if that possibility is presented as the primary problem.

Referral

When available, consider referring the child to a pediatric rheumatologist to manage care.

Active treatment

is usually successful. Order functional aerobic training using the involved limbs, such as drills, running, play activities, and swimming for a period of 5 hours daily. Desensitize the skin with towel rubbing. Refer for psychological evaluation and provide psychotherapy as appropriate. This intensive treatment may require inpatient care with a follow-up home program for another month.

Outcome

80% cured, 15% improved, 5% unimproved; relapse 15%; 90% doing well at five years.

Traction

Traction still has a role in management. Although less than in the past, specific indications have replaced standard management.

Common Indications for Traction

Temporary stabilization

Skin traction is commonly used for femoral shaft fractures before cast immobilization or operative fixation and for preoperative management of unstable proximal femoral epiphyseal slips.

Home traction

Home traction programs have been used for preliminary traction in DDH management [A] and in home management of femoral shaft fractures in young children.

A Skin traction for DDH Sometimes prereduction skin traction is used to overcome contractures to facilitate reduction and possibly reduce the risk of AVN.

Fracture management

The common uses of traction include supracondylar humeral fractures, femoral shaft [B] fractures, and subtrochanteric fractures.

B Distal femoral traction This is the preferable site for traction when treating femoral shaft fractures.

Overcoming contracture

Traction is sometimes used to improve motion in Perthes disease or chondrolysis of the hip. Whether the improvement is due to the traction or simply the enforced bed rest and immobilization is unclear.

Spine problems

Complex spine problems, such as congenital and neuromuscular deformities, are sometimes managed by a combination of traction and surgery.

Traction Cautions

Inflammatory hip disorders

Avoid traction in inflammatory hip disorders such as toxic synovitis or septic arthritis. Traction often positions the limb in less flexion, external rotation, and abduction, resulting in increased intraarticular pressure and possible avascular necrosis.

Overhead leg position

Avoid Bryant traction in patients weighing more than 25 pounds because the vertical positioning may result in limb ischemia. This traction is seldom used today. It is preferable to reduce the flexion of the hips from 90° to about 45° to reduce the risk of ischemia.

Proximal tibial pin traction

Avoid proximal tibial skeletal traction, as distal femoral traction [B] provides greater safety. Reports of recurvatum deformity and knee ligamentous laxity make proximal tibial pin traction risky.

Complications of Traction

Skin irritation

This is common under skin traction [C]. Prevent this problem by avoiding excessive traction or compression. Frequent inspection of the skin reduces this risk.

C Skin irritation under traction tapes This skin blister is due to excessive pressure and traction.

Nerve compression

This most commonly involves the peroneal nerve [D] from skin traction. Avoid excessive pressure over the upper fibula.

D Peroneal nerve palsy The excessive pressure resulted in a loss of function.

Vascular compromise

This complication is most commonly associated with overhead traction for femoral fractures in infants more than 25 pounds.

Physeal damage from pins

This complication has been most common from upper tibial pin traction.

Cranial penetration of halo pins

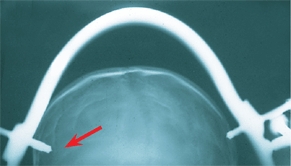

The thin calvarium in children makes inadvertent penetration a risk [E]. The risks are reduced by using more pins with less compression. Preapplication CT studies may be helpful in determining proper sites for pin placement.

E Halo pin penetration This is prevented by using multiple pins and limiting penetration pressure during application.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree