CHAPTER THIRTEEN MALINGERING

INTRODUCTION

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 13-1 COMMONLY USED PROCEDURES IN DETERMINING EXISTENCE OF COGNITIVE MALINGERING

Not all patients who feign an illness are completely aware of their actions. Some patients embellish symptoms and physical signs as learned responses or traits, whereas others describe physical problems with hysterical emotional overlays. The latter group is influenced mostly by fear of the unknown. Depression bears a significant relationship to pain (Box 13-1).

BOX 13-1 SYMPTOMS OF DEPRESSION

Data from American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ed 3, revised, Washington DC, 1987, American Psychiatric Association. In White AH, Schofferman JA: Spine care, vol. 1-2, St. Louis, 1995, Mosby.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 13-2 DSM-IV* SYMPTOM SPECIFIC CATEGORIES IN EXCESSIVE COGNITIVE SYMPTOMS

* DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

NOS, Not otherwise specified.

The diagnosis of hysteria should be established based only on positive evidence. Even if the patient has an obvious hysterical disorder, a serious organic illness may still be present.

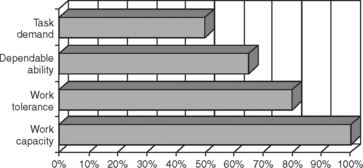

The actual percentage of patients who are malingerers is undetermined. However, estimates suggest that 2% of all patients seeking health care are malingering. Obviously, the ascertainment of the inaccuracy of a patient’s report of pain and disability is a difficult process, but the possibility of malingering should be raised in the mind of the treating physician when major discrepancies or inconsistencies appear in the patient’s medical situation. In this effort, outcome measures for the assessment of work capacity, work tolerance, dependable ability, and task demand are useful tools (Table 13-3).

TABLE 13-3 DISTINCTIONS AMONG WORK CAPACITY, WORK TOLERANCE, DEPENDABLE ABILITY, AND TASK DEMAND

|

From Demeter SL, Andersson GBJ, Smith GM: Disability evaluation, St Louis, 1996, Mosby.

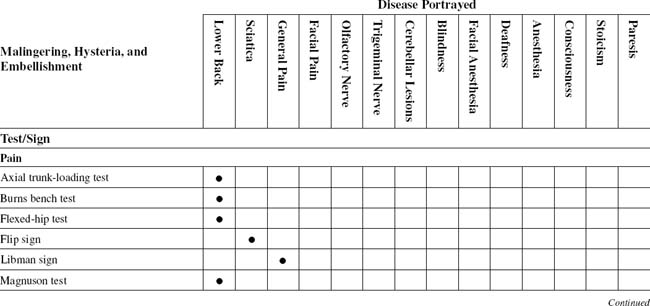

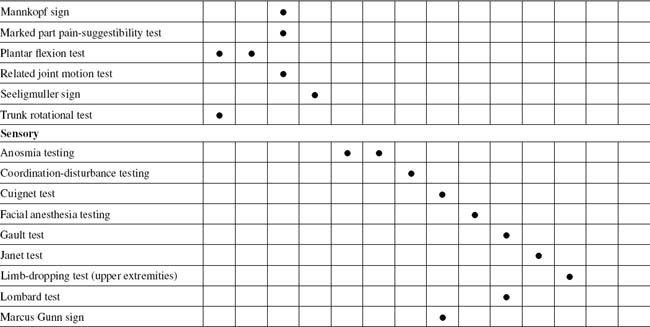

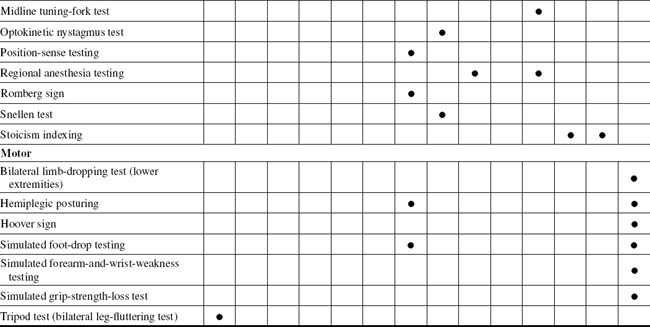

TABLE 13-2 MALINGERING, HYSTERIA, AND EMBELLISHMENT CROSS-REFERENCE TABLE BY SUSPECTED SYNDROME OR TISSUE

| Anesthesia | |

| Blindness | |

| Cerebellar lesions | |

| Consciousness | |

| Deafness | |

| Facial anesthesia | |

| Facial pain | Seeligmuller sign |

| General pain | |

| Lower back | |

| Olfactory nerve | Anosmia testing |

| Paresis | |

| Sciatica | |

| Stoicism | Stoicism indexing |

| Trigeminal nerve | Anosmia testing |

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 13-5 IMPORTANCE OF MALINGERING ASSESSMENT

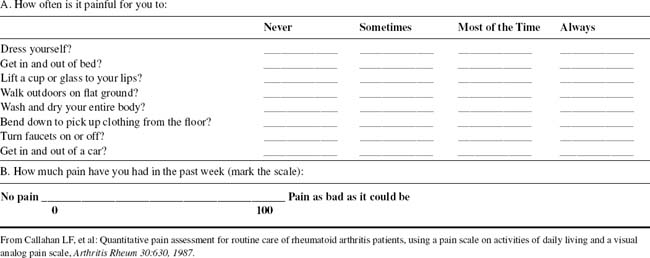

OUTCOMES ASSESSMENTS

The health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) is a self-administered instrument that assesses discomfort and disability. It is used to measure outcome in many different neuromusculoskeletal diseases. Disease-specific instruments have been produced to help follow outcomes in several other neuromusculoskeletal diseases. This area includes a fibromyalgia impact questionnaire. The activity of inflammatory neuromusculoskeletal diseases can be assessed through serologic measures. Separate measures of both tender and swollen joints can be charted on a homunculus. A generic measure of anxiety and depression, such as the hospital anxiety and depression (HAD) scale, allows psychologic variables to be assessed independently from orthopedic disease-related outcomes. The EuroQuol® thermometer is one of the instruments that uses a simple visual technique to allow people to assess their own health status; the disease repercussion profile is another such resource (Box 13-2).

BOX 13-2 DISEASE IMPACT INDEX

From Carr AJ, Thompson PW: Towards a measure of patient-perceived handicap in rheumatoid arthritis, Br J Rheumatol 33:378, 1994.

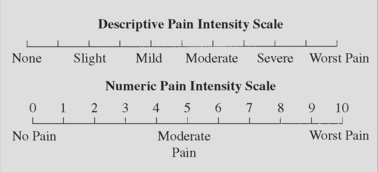

Patients report severity of problems on a 0-to-10 scale in six dimensions:

Armed with Borg pain scales, Oswestry disability indices, symptom magnification indexing, Dallas Pain Questionnaire, Waddell indexing (Table 13-4), and neuroorthopedic malingering tests, the physician is able to substantiate or refute the existence of malingering in any given case. These tests and indices are usually used in combination with the more traditional neuroorthopedic physical examinations. A singular positive finding or test does not indicate that the patient is magnifying or faking symptoms. Rather, the malingering diagnosis is based on the preponderance of positive malingering test findings and the absence of findings from traditional neuroorthopedic tests. Any positive findings must be further correlated with the medical history of the patient. The constellation of positive malingering tests, normal findings in traditional tests, and medical history discrepancies form the malingering diagnosis. Malingering and psychogenic rheumatism patients complain primarily of pain, sensory losses, or paralysis in any combination.

TABLE 13-4 NONORGANIC PHYSICAL SIGNS INDICATING ILLNESS BEHAVIOR

| Physical Disease/Normal Illness Behavior | Abnormal Illness Behavior | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Pain | Anatomic distribution | |

| Numbness | Dermatomal | Whole leg numbness |

| Weakness | Myotomal | Whole leg giving way |

| Time pattern | Varies with time and activity | Never free of pain |

| Response to treatment | Variable benefit | |

| Signs | ||

| Tenderness | Anatomic distribution | |

| Axial loading | No lumbar pain | Lumbar pain |

| Simulated rotation | No lumbar pain | Lumbar pain |

| Straight-leg-raising | Limited on distraction | Improves with distraction |

| Sensory | Dermatomal | Regional |

| Motor | Myotomal | Regional, jerky, giving way |

From Waddell G, et al: Symptoms and signs: physical disease or illness behavior? Br Med J 289:739, 1984, British Medical Association.

GENERAL PROCEDURES

Psychogenic Rheumatism Profile

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 13-6 REASONS FOR PSYCHOLOGIC ILLNESS THAT CAUSE THE APPEARANCE OR EXACERBATION OF PAIN

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 13-7 PSYCHOGENIC RHEUMATISM*

Symptoms and signs of psychogenic rheumatism are:

BOX 13-3 CLINICAL SYMPTOMS OF ANXIETY

From White AH, Schofferman JA: Spine care, vol 1-2, St Louis, 1995, Mosby.

BOX 13-4 DSM-III-R* CRITERION FOR ANXIETY

Data from American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ed 3, revised, Washington DC, 1987, American Psychiatric Association. In White AH, Schofferman JA: Spine care, vol. 1-2, St. Louis, 1995, Mosby.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 13-8 COMBINED EMORY AND ELLARD INCONSISTENCY PROFILES*

Data from Ellard J: Psychological reaction to compensable injury, Med J Australia 2:349-55, 1970; and Brena SF, Chapman SL: Pain and Iitigation: textbook of pain, London, 1984, Churchill Livingstone.

BOX 13-5 MOOD DISORDERS—DSM-III-R* CLASSIFICATIONS

Data from American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ed 3, revised, Washington DC, 1987, American Psychiatric Association. In White AH, Schofferman JA: Spine care, vol. 1-2, St. Louis, 1995, Mosby.

* DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, revised.

Fifth digit (x) allows coding of current state of disorder: 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe, without psychotic features; 4 = with psychotic features; 5 = in partial remission; 6 = in full remission; 0 = unspecified

BOX 13-6 DESCRIPTION OF MMPI-2*

From White AH, Schofferman JA: Spine care, vol 1-2, St Louis, 1995, Mosby.

L, F, and K are validity scales.

Special Hand Signals by the Patient

How a patient uses the hands to describe the area of pain is useful in determining the validity of the complaints. At first, malingering patients take care not to touch the area they claim experiences pain. Because the complaint is a sham, touching of the part abets the lie. The examiner often inadvertently aids this process by physically touching the area of complaint before the patient has. The patient now only has to agree with the frustrated examiner concerning the exact location of the pain (Fig. 13-1).

The psychogenic rheumatic patient uses the whole hand to paint the area of involvement with pain. Because this type of patient perceives the lesion abnormally, the distribution is painted to cover a whole body part. This pain crosses more than one dermatome boundary, and this patient’s discomfort is real. The discomfort may have origin in an organic lesion, but because of learned responses or fear, the patient rubs the whole part with the hand to indicate its extent. Careful questioning and guidance will help this patient better define the most focal trigger areas (Fig. 13-2).

Patients with organic, pain-producing lesions are concerned that the source of the pain might be missed. When directed to point to the pain, this type of patient will touch the part with one or two fingers, which is representative of a more focal appreciation of the discomfort. In severe expression of the symptoms, this patient also may place the examiner’s hand on the exact location of the pain. These patients do not want to risk having the source missed and not treated (Fig. 13-3).

PAIN QUALIFICATION AND QUANTIFICATION

Overview

Pain disrupts the life of the individual in terms of relationships with others, self-esteem, ability to complete tasks of daily living and to work, and ability to function as a member of the community. Disability is strongly correlated with attitude to illness; these considerations underlie the importance of assessing patients’ beliefs regarding the nature and prognosis of their pain (Table 13-5).

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 13-9 RELAY STATIONS

Three main relay stations for sensory stimuli from the periphery to the sensory cortex include:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 13-11 CLINICAL FEATURES OF BURNING MOUTH SYNDROME

Adapted from Patton LL et al: Management of burning mouth syndrome: systematic review and management recommendations, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol 103(suppl 1):S39.e1-S39.e13, 2007.