28 Lumbar degenerative disk disease (DDD) and low back pain (LBP) are common conditions, with more than 12 million Americans diagnosed each year, and 70% to 85% of adults affected by LBP at some point during their lifetimes. The sequelae of DDD are among the leading causes of functional incapacity and a common source of chronic disability in the working years. Diagnostic options and surgical interventions for LBP due to lumbar DDD without radicular symptoms are controversial, and clinicians are left without clear evidence as to the best avenues for accurately diagnosing and effectively managing this common and debilitating condition. This chapter reviews the workup of the patient with discogenic LBP, including physical examination, imaging, and special diagnostic studies, and presents available treatment options for the condition, including current nonsurgical and surgical interventions as well as future biologic options. LBP due to DDD is believed to be a result of the loss of normal structure and function of the intervertebral disk. Although lumbar DDD is a recognized cause of LBP, it is important to note that disk degeneration can occur in the absence of back pain or other symptoms in over 30% of individuals by age 30, in 50% of individuals by age 50, and nearly 100% of 80-year-old individuals.1 The etiology of degenerative disk changes is multifactorial and can be related to aging, wear and tear, environmental factors, such as nutrition and cigarette use, or even genetics. In a degenerating disk, over time, the collagen structure of the annulus fibrosus weakens and the proteoglycan content decreases. These physiologic changes lead to a decrease in the water content of, and nutritional supply to, the disk, making it more susceptible to mechanical stresses. This progresses to altered spinal biomechanics, which, combined with release of neural mediators and neurovascular ingrowth into the disk, generate LBP.2 Continued degeneration of an affected disk can lead to secondary problems, such as degenerative spondylolisthesis, lumbar stenosis, and facet arthrosis, which are not the focus of this chapter. The clinical presentation of a patient with discogenic LBP is variable. An acute or insidious onset can be described, and a variety of alleviating and aggravating factors are often implicated. Differentiating between acute and chronic LBP is important because the natural history, treatment, and prognosis are different. Lower-extremity radicular symptoms are typically absent, unless there is an associated disk herniation or foraminal stenosis. Claudication symptoms are likewise generally absent unless concomitant spinal stenosis is also present. It is imperative to differentiate discogenic LBP from the aforementioned entities before proceeding with diagnostic and therapeutic measures.3 Screening for secondary gain issues and inconsistencies is also important. The goal of the history and exam in a patient with LBP is to determine a likely etiology, evaluate treatments already rendered, and rule out serious pathology (“red flags”), such as neural compromise, trauma, neoplasm, and infection. Patients with primarily discogenic LBP usually have an unremarkable physical examination. Regardless, a thorough exam should still be performed. The patient should be observed closely while walking and during movement to and from the examination table, which may reveal an antalgic gait and guarding during transfers. A meticulous neurological exam usually will not reveal any focal findings. Provocative tests, such as the straight leg raise and femoral stretch test, are usually negative. There may be limited range of motion of the lumbar spine, with greater pain typically in flexion. “Red flag” symptoms, such as bowel or bladder changes, fevers, night sweats, or unexplained weight loss, should be absent with this diagnosis. Upright plain anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs, including flexion and extension views, should be the first study used in the evaluation of the lumbar spine. These radiographs should be evaluated for coronal and sagittal alignment, as well as for the presence of degenerative changes, including osteophyte formation, foraminal narrowing, disk space narrowing, endplate sclerosis, and vacuum phenomenon within the disk. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of spinal soft tissues and disk detail. MRI must be used carefully as an adjunct to the clinical presentation, history, and physical examination, as 30% of asymptomatic individuals show degenerative disk changes on MRI.1 MRI, however, is not initially indicated in the majority of patients presenting with LBP due to DDD. If there is concern for malignancy, infection, or if red flag or neurologic symptoms are present, MRI should be obtained. For LBP due to DDD that is unresponsive to reliable nonsurgical intervention after 3 to 6 months, MRI can be a useful diagnostic adjunct. Signs of degeneration, endplate changes, presence or absence of annular tears, Modic changes, or the presence of high-intensity zones all can be evaluated on an MRI.4 Unfortunately, the low sensitivity and specificity of these MRI findings limit their usefulness. Diskography is a potentially helpful adjunct in the diagnostic algorithm for LBP due to DDD, as it is the only diagnostic modality that involves direct stimulation of the potentially offending disk. Diskography must involve a low-pressure injection, must involve abnormal morphology (extravasation), must reproduce the patient’s usual pain, and should be nonpainful at control levels to be considered a reliable test. As diskography relies on the patients’ subjective reporting of their pain, it is limited in its diagnostic reliability, leading to significant debate and controversy over its effectiveness. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that abnormal psychometric testing further skews diskographic results.5 Accordingly, diskography is largely considered an available diagnostic tool but not an initial or confirmatory diagnostic test. The mainstay of treatment for patients with chronic LBP due to DDD is nonsurgical management. After an appropriate diagnostic workup ruling out serious pathology, including neoplasm, trauma, and infection, and in the absence of any neurologic or motor deficits, a 6-month regimen of active physical therapy, behavioral modification (i.e., smoking cessation), weight loss, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be instituted.6 Care should be taken to evaluate imaging studies for correlative pathology that could account for the pain, such as segmental instability, pars interarticularis defects, or deformity, rather than just generalized DDD. Approximately 90% of individuals with LBP due to generalized DDD will have resolution of their symptoms within 3 months with or without treatment, the majority of cases resolving in as little as 6 weeks. Interventional procedures such as spinal epidural steroid injections (ESIs) have long been used to treat discogenic LBP. Although no studies support the use of ESIs in the treatment of LBP, their success in selected patients warrants consideration as an alternative to surgical intervention.7 The use of intradiskal electrothermal therapy (IDET) in the treatment of discogenic back pain remains controversial. There are no good long-term studies demonstrating conclusive benefit, and the procedure is not recommended for general use.8 Surgical intervention for LBP due to DDD that has failed extensive conservative measures can be divided into two broad categories: arthrodesis (fusion) and non-fusion options. Unfortunately, all surgical interventions for discogenic back pain provide inconsistent results and are the subject of significant controversy. Arthrodesis can be approached in an open or a minimally invasive fashion, and includes posterolateral, posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), transforaminal interbody fusion (TLIF), or anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF). None of these forms of arthrodesis have been demonstrated to be superior to the others in the surgical management of discogenic LBP, and conflicting data exists as to the benefit of arthrodesis compared with nonsurgical management. A well-established complication of spine fusion surgery is adjacent segment disease.3 This has led to the development of non-fusion options for the treatment of LBP due to DDD, which allow motion to be preserved at the diseased spinal segment, theoretically slowing the degeneration at adjacent segments. The efficacy of this broad class of interventions, including soft-tissue stabilization procedures, interspinous spacers, and dynamic stabilization systems, has not been validated in the literature for the treatment of LBP. Finally, total disk arthroplasty (TDA) is being studied as an alternative to fusion for the treatment of symptomatic DDD. Much as with other motion-sparing non-fusion technologies, the major advantage of TDA is the preservation of motion at the diseased level and prevention of adjacent-level degeneration and disease. TDA has been approved in the United States for the treatment of single-level back pain without instability.9 TDA has been shown to preserve motion at the surgical level; however, it has not been demonstrated to reduce the incidence of adjacent-level disease. Current randomized controlled clinical trials demonstrate that single-level TDA is equivalent to lumbar fusion in reducing back pain. LBP due to lumbar DDD is a commonly encountered problem that is challenging to treat. Initial diagnostic imaging should include plain radiographs, and, in the absence of any neurologic findings or “red flags,” initial management should be nonoperative. For the select population of patients who fail extensive conservative management, available surgical interventions include both fusion and non-fusion options. 1. Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990;72(3):403–408 PubMed 3. Madigan L, Vaccaro AR, Spector LR, Milam RA. Management of symptomatic lumbar degenerative disk disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17(2):102–111 PubMed 4. Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS, Carter JR. Imaging of degenerative disk disease. Radiology 1988;168(1):177–186 PubMed 5. Carragee EJ, Lincoln T, Parmar VS, Alamin T. A gold standard evaluation of the “discogenic pain” diagnosis as determined by provocative discography. Spine 2006;31(18):2115–2123 PubMed 6. van Tulder MW, Scholten RJ, Koes BW, Deyo RA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 2000;25(19):2501–2513 PubMed 7. DePalma MJ, Slipman CW. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with epidural steroid injections. Spine J 2008;8(1):45–55 PubMed 8. Freeman BJ, Fraser RD, Cain CM, Hall DJ, Chapple DC. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial: intradiscal electrothermal therapy versus placebo for the treatment of chronic discogenic low back pain. Spine 2005;30(21):2369–2377, discussion 2378 PubMed 9. Freeman BJC, Davenport J. Total disc replacement in the lumbar spine: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Spine J 2006;15(Suppl 3):S439–S447 PubMed Fritzell P, Hägg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A; Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine 2001;26(23):2521–2532, discussion 2532–2534 PubMed This important study found that lumbar fusion in a well-informed and selected group of patients with severe chronic LBP can diminish pain and decrease disability more efficiently than commonly used nonsurgical treatment. Mirza SK, Deyo RA. Systematic review of randomized trials comparing lumbar fusion surgery to nonoperative care for treatment of chronic back pain. Spine 2007;32(7):816–823 PubMed This systematic review determined that surgery may be more efficacious than unstructured nonsurgical care for chronic back pain but may not be more efficacious than structured cognitive-behavior therapy. Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. JAMA 2006;296(20):2451–2459 PubMed This important publication of results from the SPORT trial determined that patients with persistent sciatica from lumbar disk herniation improved in both operated and usual care groups. Those who chose operative intervention reported greater improvements than patients who elected nonoperative care. However, the authors were careful to note that nonrandomized comparisons of self-reported outcomes are subject to potential confounding and must be interpreted cautiously. Madigan L, Vaccaro AR, Spector LR, Milam RA. Management of symptomatic lumbar degenerative disk disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17(2):102–111 PubMed This recent summary article provides an excellent outline of the various modalities available for management of symptomatic DDD and the literature supporting each. Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS, Carter JR. Imaging of degenerative disk disease. Radiology 1988;168(1):177–186 PubMed This classic article describes the imaging modalities available for diagnosing DDD and the benefits of each. van Tulder MW, Scholten RJ, Koes BW, Deyo RA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 2000;25(19):2501–2513 PubMed This study provides an excellent systematic review of the utility of NSAIDs for LBP. The authors conclude that the evidence from the 51 trials suggests that NSAIDs are effective for short-term symptomatic relief in patients with acute LBP. Furthermore, there does not seem to be a specific type of NSAID that is clearly more effective than others. Sufficient evidence on chronic LBP still is lacking. CT, computed tomorgraphy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Lumbar Disk Disease and Low Back Pain

![]() Natural History

Natural History

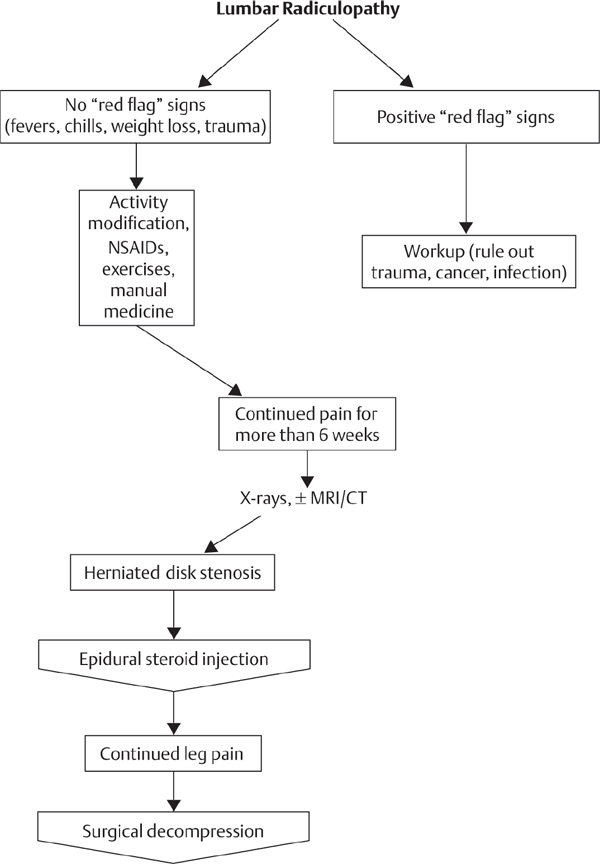

![]() Workup

Workup

History and Clinical Presentation

Physical Examination

Radiographic Imaging

Other Diagnostic Studies

![]() Treatment

Treatment

Nonsurgical

Interventional

Surgical

![]() Summary

Summary

References

Suggested Readings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree