Fig. 22.1

En coup de sabre scleroderma in a 10-year-old girl: frontal-parietal linear lesion resembling the stroke of a sword

Fig. 22.2

Parry-Romberg syndrome in a 14-year-old patient, leading to progressive facial hemiatrophy of the left side of the face

Differential Diagnosis

LSF should be distinguished from other conditions affecting the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, such as partial progressive lipodystrophy, focal dermal hypoplasia, or atrophoderma after intramuscular injections of corticosteroids or vitamin K. The initial stage of LSF should be differentiated from annular erythema, erythema migrans, and sarcoidosis. The atrophic lesions of LSF should be distinguished from lichen sclerosus and atrophicus or other forms of panniculitis, especially the lupus-induced variety, called lupus profundus. The differential diagnosis of the latter with linear scleroderma as well as with deep morphea may be difficult. Even the biopsy is not always conclusive in this respect [9]. However, the circumscribed appearance of the lesions, presenting as sclerotic frontoparietal bands on one side of the face; the presence of serum autoantibodies; and the aggressive course, in most of the cases, are strongly suggestive of LSF [3].

Pathology

The skin biopsy is not mandatory to make the diagnosis of LSF; however, it could be advisable to confirm it in doubtful cases. When taking a specimen, the excision should be deep enough to include the subcutis, fat tissue, fascia, and muscle to exclude possible involvement of inner structures. Apart from the lack of intimal fibrosis due to microvascular damage, typical of systemic sclerosis (SSc), no reliable histological criteria of discernment between LSF and SSc are actually available. Despite the limitations of being invasive, skin biopsy should be performed mainly to confirm the diagnosis of LSF, to differentiate it from other fibrotic disorders, and to assess the depth of lesion. The early stage (inflammatory) is characterized by thickened collagen bundles with perivascular and periadnexal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the reticular dermis, sometimes extended to the subcutis (Fig. 22.3). In the late stage (sclerotic), newly formed collagen replaces most of the subcutaneous fat, with resulting displacement of the eccrine glands higher in the dermis [10, 11].

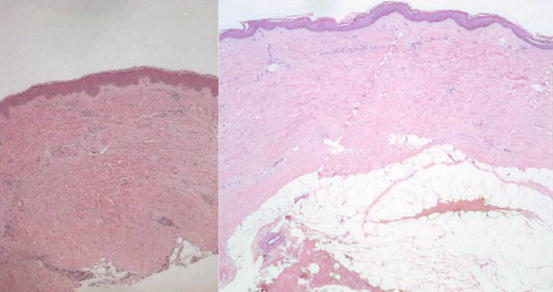

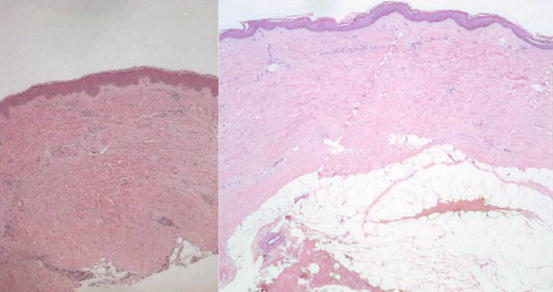

Fig. 22.3

Normal skin on the left image compared with morphea on the right. The latter is characterized by thickening of collagen bundles extending to the region of the subcutaneous fat, atrophy of the eccrine glands, and mononuclear cell infiltrates (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining, original magnification 25x)

Diagnostic Flowchart

The diagnosis of LSF is mainly clinical (Fig. 22.4). Despite the lack of specific serologic parameters, blood tests are considered the first step to confirm the diagnosis. Hypergammaglobulinemia and eosinophilia are quite common in children with LSF, while ANA positivity, regarded by many authors as an epiphenomenon, is nonetheless detectable in up to 50% of the patients [3].

Pivotal is the role of the biopsy, especially for differential diagnosis and assessment of therapeutic effectiveness. When the diagnosis of LSF is made, the involvement of both eye and CNS should be excluded by an ophthalmological examination and CNS imaging (cerebral MRI and/or CT scan), respectively.

Disease Monitoring

The assessment of lesion activity and extension is crucial to guide both the therapeutic approach and the follow-up (Fig. 22.5). Both lesion activity and extension can be evaluated through clinical scores (LoSSI) [12] and ultrasonography (USG) 20 MHz probes [13]. Unfortunately, both tools are operator dependent, and therefore not totally reliable.

Fig. 22.4

Disease monitoring

Inflammatory activity may be detected by infrared thermography [14] or by laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) [15]. In Parry-Romberg syndrome, thermography may sometimes give false-positive results on silent, atrophic lesions, so a correlation with a careful clinical examination is always needed.

Lesion extension can be also assessed by objective techniques, such as CT scan and MRI, which are also essential for the surgical planning. Despite their high reliability and reproducibility, these techniques present some limitations in children, such as high radiation exposure (CT scan), need for general sedation or prolonged immobilization, and costs. A computerized skin score (CSS) was recently proposed for the standardized assessment of disease extension [16].

Treatment

Since there are not validated guidelines, yet, the management and treatment of LSF is challenging (Fig. 22.6). Table 22.1 summarizes the drugs most frequently used in LSF with their dosage. While for circumscribed isolated lesions, a local treatment with topical agents and phototherapy has been suggested [17]; for linear active lesions, a more aggressive systemic therapy is recommended, given the progressive nature of the disease [1, 18, 19].

Fig. 22.5

Treatment approach of localized scleroderma of the face

Table 22.1

Treatments most frequently used in localized scleroderma of the face

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree