Local and Regional Soft Tissue Coverage of the Hand

CASE PRESENTATION

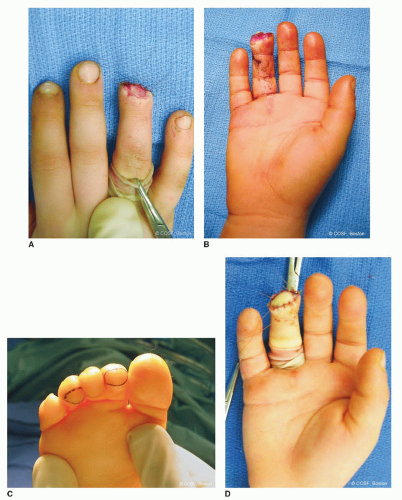

A 4-year-old male presents emergently for evaluation of a fingertip amputation sustained after the right ring finger was caught in a closing door (Figure 43-1). The digital tip was avulsed and lost. Examination demonstrates a transverse fingertip amputation through the level of the distal phalanx with minimal contamination and exposed bone.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

What are the patterns of fingertip injuries/amputations in children? How does the pattern of injury dictate treatment?

What is the reconstructive ladder?

What are the treatment options for patients with fingertip avulsions without bone exposed?

What are the treatment options for fingertip amputations with exposed bone?

In cases of more severe hand trauma, what are the indications and treatment options for soft tissue coverage of the hand?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Fingertip injuries are common in the pediatric population, particularly in toddlers and younger children. Although less common, severe combined injuries of the hand do occur and present their own set of clinical challenges. Awareness of the treatment principles and surgical options is essential for the pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeon. As each patient will present with unique anatomic and clinical considerations, the ability to use a number of different surgical tools will allow for individualized care and maximization of outcomes. Furthermore, as traumatic bony and soft tissue loss occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, the time of initial evaluation and clinical treatment is often emotionally charged and psychologically stressful for patients and families alike. Clear communication and thoughtful clinical approaches will ease anxieties, facilitate timely and definitive care, and establish realistic expectations for long-term results.

As discussed below, nonoperative and surgical treatment is based upon a number of patient and injury characteristics, including (1) size and depth of wound; (2) whether there is exposed bone, tendon, or neurovascular structure; (3) degree of wound contamination; (4) availability of local or remote tissue to assist with coverage; and (5) patient and family sophistication and compliance. Regardless of which treatment option is undertaken, thorough wound debridement is critical for prevention of infection and optimization of wound healing.1

Etiology and Epidemiology

Fingertip injuries, though most common in toddlers and younger children, affect patients of all ages. The vast majority of injuries are due to traumatic crush-avulsion mechanisms, such as when the affected digit is caught in a closing door or beneath heavy objects. Furthermore, in this age of increasing, high-energy sports participation, more fingertip and hand injuries are seen from sports-related activities. Therefore, the peak ages for incidence of finger injuries are toddlers (crush) and adolescents (sports). Classification is typically descriptive and anatomic.

Clinical Evaluation

We try to stress the little things because little things lead to big things.

—Steve Alford

FIGURE 43-1 Clinical photograph depicting a transverse fingertip amputation of the right ring finger. |

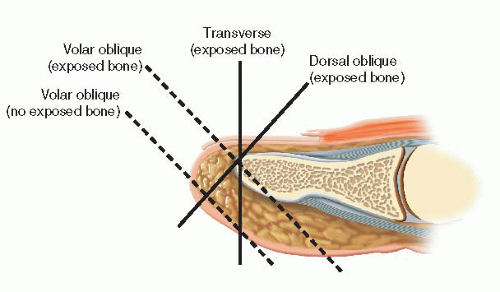

Despite the sense of urgency that often accompanies the initial evaluation of patients with traumatic fingertip amputations or soft tissue loss, a thorough history and clinical examination should be performed. As with other traumatic conditions, hand dominance, functional demands, and any associated medical comorbidities must be documented. Careful assessment of wound contamination, vascular status, and the condition of proximal soft tissues (nerves, tendons, subcutaneous tissue, and skin) should be done. Furthermore, characterization is made for the pattern of tissue loss, which will help determine the most appropriate reconstructive technique (Figure 43-2). All amputated parts should be salvaged, saved, and examined for possible repair, replantation, or use as “spare parts.” Radiographic evaluation of the affected anatomic parts is necessary to assess for the presence and pattern of skeletal injury and/or articular involvement. With more proximal amputations, x-rays of both the injured finger and amputated part are helpful in reconstructive planning. Antibiotics and tetanus boosters should be provided in the emergency setting. The injured hand/upper limb is irrigated with sterile saline and bulky soft bandages, and splint immobilization is applied. The amputated part is wrapped in saline-soaked gauze and placed in a sterile container.

Surgical Indications

The goal of treatment for fingertip injuries is the reconstitution of a durable, sensate, viable digital tip that possesses adequate bony coverage and, if possible, preserves digital length. As a host of treatment options are available, the particular reconstructive strategy must be tailored to each individual patient. Surgical indications are therefore equally variable. In general, surgical treatment is indicated in cases of extensive fingertip soft tissue loss exceeding 1 cm2 in cross-sectional area and/or bone exposed. It should be noted that the vast majority of simple fingertip injuries may be treated effectively with nonoperative means, particularly in young children, who demonstrate great healing potential.

In cases of more extensive soft tissue loss, treatment is indicated for coverage of bony, tendinous, or neurovascular structures that cannot be achieved by simple primary closure alone.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Good sound habits are more important than rules—use concepts.

—Mike Krzyzewski

While a host of surgical procedures are within the armamentarium of the pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeon, a few fundamental principles are universally applicable. First, every effort should be made to avoid infection by thorough irrigation and debridement of contaminated wounds and timely soft tissue (and bony)

reconstruction. Second, in a child, emphasis is placed on preserving digital length, function, and growth potential whenever practical. Finally, simpler solutions are favored over more complex solutions, particularly in the anxious, distressed, often nonverbal child in whom multiple procedures and/or anesthetics are to be avoided.

reconstruction. Second, in a child, emphasis is placed on preserving digital length, function, and growth potential whenever practical. Finally, simpler solutions are favored over more complex solutions, particularly in the anxious, distressed, often nonverbal child in whom multiple procedures and/or anesthetics are to be avoided.

FIGURE 43-2 Schematic diagram depicting the patterns of digital tip loss: dorsal oblique, transverse, and volar oblique. |

Table 43.1 The reconstructive ladder2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The “reconstructive ladder” has been proposed to guide the surgeon on treatment options2 (Table 43.1). Each successive “rung” of the reconstructive ladder represents a more complex surgical strategy to achieve soft tissue coverage and should only be considered if simpler, less complicated procedures are ruled out. Pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeons should be familiar with these surgical options, and a systematic approach to reconstructive decision making is recommended.

• Primary Wound Closure, Healing by Secondary Intention, Bony Shortening and Primary Closure or Healing by Secondary Intention

Simple solutions are possible in the vast majority of pediatric fingertip injuries. When there is adequate skin and soft tissue available, primary wound closure is easy, effective, and almost universally successful. In cases with uncovered distal phalangeal bone, simple skeletal shortening by rongeuring the exposed tip of the distal phalanx will allow for primary wound closure or adequate healing by secondary intention.

In these cases, small defects (<1 cm2 in cross-sectional area) may be treated with serial dressing changes, allowing the wound to heal by secondary intention.3, 4, 5 and 6 When wound healing by secondary intention is pursued, the primary dressing may be left in place for 1 to 2 weeks in cases of clean uncontaminated wounds. At this time, once there is confirmation that there is no infection, parents and families may be instructed on daily half-strength hydrogen peroxide soaks and dressing changes. Our preference is to use petrolatum gauze (Xeroform, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) and Coban self-adherent wrap (3M, St. Paul, MN) to the affected digit. While the long-term results are highly satisfactory in terms of both sensibility and aesthetic appearance, this strategy takes time and may be challenging in the very young patient. Parents and other care providers must be dedicated and sophisticated in their understanding and adherence to this treatment plan.

▪ Split-Thickness Skin Grafts, Full-Thickness Skin Grafts, and Composite Grafts

Skin grafting for fingertip injuries is rare in children. A prerequisite to skin grafting is an uncontaminated recipient soft tissue bed; adequate vascularity to support graft healing; and no exposed bone, tendon, or neurovascular bundles.

Split-thickness skin grafting (STSG) is rarely used in the hand except for large palmar areas of skin loss, such as with deep burns. The STSG is used in delayed closure of large traumatic forearm wounds, such as post fasciotomies for compartment syndromes, when there is an underlying bed of healthy muscle. The graft donor site is usually the upper posterior thigh to lessen the poor aesthetics of the resultant scar. An appropriate-size dermatome to match the recipient site is utilized. Usually this is 0.015″. Mineral oil is placed on the donor site, and tension is maintained on the dermatome throughout the harvest to obtain a uniform thickness graft. The STSG is meshed with standard equipment and then placed with mild tension over the recipient site. The STSG is sutured in place, so there is adherence of the graft over the entire recipient site. A petrolatum gauze (Xeroform, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) and moist cotton bolster are secured over the graft to promote healing. This is removed in the office at 5 to 14 days, depending on the clinical scenario.

Full-thickness skin grafting (FTSG) may similarly be utilized in cases of large (>1 to 2 cm) skin loss with adequate vascularized subcutaneous tissue. Skin grafts are not indicated in cases of exposed bone, tendon, or cartilage, and they may lack the bulk and durability desired for hand function; for this reason, it is unusual for skin grafts to be used in cases of fingertip avulsions or digital tissue loss. Potential donor sites for FTSG include the inguinal fold (lateral to the palpable femoral pulse to avoid harvest of future hair-bearing skin), antecubital flexion crease, wrist flexion crease (though this is not preferred given the potentially aesthetically and socially unpleasing transverse scar), and hypothenar eminence of the hand.7 Ideally, glabrous skin of equal pigmentation is chosen to achieve a more durable and aesthetically pleasing result. After harvest and defatting, the skin graft may be sewn in using multiple interrupted 5-0 or 6-0 polyglactin suture (Chromic, Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ), the tails of which are left long to secure a saline-soaked cotton and petrolatum gauze (Xeroform, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) bolster, which is placed over the graft to promote adherence and subsequent graft take. Dressings and the petrolatum gauze-cotton bolster may be removed after 2 weeks, and near-universal take is expected in young, healthy children with clean, vascularized soft tissue beds.

Another strategy that is particularly helpful for fingertip reconstruction in children is the use of composite grafts. If the amputated digital tip is available, it may be repaired primarily; in children, there is a higher likelihood of healing than in adults.8,9 In cases where the digital tip is not available, contaminated, or too damaged to allow for “repositioning,” composite toe grafting may be performed10,11 (Figure 43-3). Under general anesthesia and digital tourniquet control, an elliptical-shaped incision is made over the plantar pulp of one of the lesser toes, the dimensions of which are determined by the size of the fingertip defect. Skin and approximately 4 mm of subcutaneous fat are excised as a composite graft. Provided that the major axis of the ellipse is two to three times greater than the minor axis, the donor defect may be easily closed primarily with multiple interrupted 4-0 or 5-0 polyglactin suture (Chromic, Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ), followed by application of a simple bandage. The composite graft is then placed in the recipient bed and reapproximated using multiple interrupted 5-0 polyglactin suture (Chromic, Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ), the tails of which are left long to secure a saline-soaked cotton and petrolatum gauze (Xeroform, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) bolster secured over the graft site. Sterile bandages are applied, followed by cast immobilization in the very young to ensure compliance with postoperative care.

▪ Local Advancement Flaps (V-Y, Moberg, Thenar)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree