Chapter 7 Lifestyle Interventions and Behavior Change

Prevention from the Disease-Oriented Perspective: A Focus on Heart Disease

The leading causes of death for all adults age 50 to 85 are listed in Table 7-1. A look at this list can provide a guide to action for your practice. If the number-one cause of death is heart disease, this may be the problem to address most vigorously, perhaps delaying other preventive activities until this is done. Alternatively, some might argue for a focus on cancer, because mortality from cancer is almost as high as from heart disease (and even higher in the age group 50-59), and cancer causes much more concern among patients.

Table 7-1 Ten Leading Causes of Death—United States, 2006∗

| Rank | Cause | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heart disease | 598,747 |

| 2 | Cancer (all types) | 520,129 |

| 3 | Stroke | 131,312 |

| 4 | Chronic lung disease | 121,824 |

| 5 | Alzheimer’s disease | 72,388 |

| 6 | Diabetes mellitus | 67,295 |

| 7 | Accidents | 57,089 |

| 8 | Pneumonia and flu | 53,676 |

| 9 | Chronic nephritis | 42,123 |

| 10 | Septicemia | 31,594 |

∗ All races, both genders; age groups: 50 to 85+.

Data from http://webapp.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus.html.

However, good reasons exist not to focus on cancer. The first problem is that “cancer,” when listed as the second leading cause of death in the United States, represents deaths from “all cancers.” The disadvantage is that physicians have no good tools or tests that work against “all” cancers; the single exception is discussed later. Many mammograms are needed for breast cancer, many sigmoidoscopies or colonoscopies for colon cancer, and many Pap smears for cervical cancer, to follow the conventional wisdom about how to reduce the effects of these cancers.

Because these cancers are relatively rare, however, and because the tools are relatively inefficient, a cancer-focused approach to reducing overall mortality tends not to work. In fact, a 2002 review of cancer screening concluded that there is no evidence that cancer screening, as currently conducted, results in reductions of all-cause mortality (Black et al., 2002). Thus, even perfect compliance for all the traditionally recommended cancer programs may dramatically reduce a person’s risk of dying of cancer, but it would not add a single day of life to this person’s life span. Table 7-2 illustrates the failure of most cancer screening programs, even when they have a significant impact on the target cancer, to alter the ultimate bottom line: all-cause mortality.

Table 7-2 Comparison of Disease-Specific Mortality and All-Cause Mortality Associated with Traditional Cancer and Cardiovascular Prevention Strategies

| Intervention | Change in Disease-Specific Mortality∗ | Change in All-Cause Mortality† |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Prevention | ||

| Pap smears | Cervical cancer: 20%-60% reduction after 17 or more Pap smears | 0 |

| Colorectal cancer: 15% reduction after 20 or more FOBTs plus follow-up colonoscopy in patients with positive results | 0 | |

| Breast cancer: 16% reduction after 20 mammograms | 0 | |

| Prostate cancer: 0% reduction after 25 PSA tests | 0 | |

| DRE, breast self-examination (BSE), physical examination | 0% reduction after 40 years | 0 |

| Statins (AFCAPS/TexCAPS Study)‡ | 37% reduction in combined myocardial infarction, unstable angina, and stroke | 0 |

| Eight major lifestyle studies (see Tables 7-3 and 7-4): chronic disease and death | 40%-65% | |

| Secondary Prevention | ||

| 4S Simvastatin Study§ | 30% | |

| West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS)⁋ | Statins reduced coronary events by 31% and cardiovascular specific mortality by 32%. | 0 |

| The MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study¶ | 25% reduction in first-event rate for nonfatal myocardial infarction or coronary death, fatal or nonfatal stroke, and for coronary revascularization with 40-mg simvastatin in high-risk patients over 5 years in 20,536 U.K. adults age 40-80 years | 12.9% |

| Beta blockers after myocardial infarction# | 27% reduction of nonfatal infarction in 25 randomized trials (>23,000 patients) | 22% |

∗ All data from current U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) appraisal of the evidence and recommendations. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf08/colocancer/colors.htm#rationale; http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/cervcan/cervcanrr.htm; http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/breastcancer/brcanrr.htm; http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf08/prostate/prostaters.htm.

† Black WC, Haggstrom DA, Welch HG. All-cause mortality in randomized trials of cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:167-173.

‡ Downs JR et al., for AFCAPS/TexCAPS Research Group. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. JAMA 1998;279:1615-1622.

§ Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S Study). Lancet 1994;344:1383-1389.

⁋ Shepherd J et al., for West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 1994.

¶ Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7-22

# Yusuf S, Wittes J, Friedman L. Overview of results of randomized clinical trials in heart disease. I. Treatments following myocardial infarction. JAMA 1988;260:2088-2093.

A short list of the most important interventions, those with large effect size in secondary prevention, are also summarized in Table 7-2. Physicians preferring the disease treatment model for medicine who want to believe their work is important and measurably effective should select at least one strategy from this table.

Why focus on global cardiac risk? Leading national and specialty-based expert groups have endorsed this as the most important parameter for addressing cardiac health (Grundy et al., 1999). The Adult Treatment Panel Report (ATP II) of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP), the Joint National Committee of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program, and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) all advocate “adjusting the intensity of risk factor management to the global risk of the patient.” The NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (ATP III, 2001) stated specifically, “A basic principle of prevention is that the intensity of risk-reduction therapy should be adjusted to a person’s absolute risk. Hence, the first step in selection of LDL-lowering therapy is to assess a person’s risk status…. In ATP III, a primary aim is to match intensity of LDL-lowering therapy with absolute risk.” Hypertension experts John Laragh, Bruce Psaty, and Curt Furberg have directly endorsed explicit global cardiac risk assessment as the new standard of care:

Most current guidelines focus primarily on the management of individual cardiovascular risk factors, such as high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes. A more appropriate clinical approach to reducing cardiovascular disease risk would be based on a comprehensive evaluation of risk profile, and accurate stratification of global (absolute) risk in individual patients…. The decision to treat a patient should be based on the level of global risk, rather than on the level of a single risk factor…. We proposed that global risk should be used as the main determination of whom to treat, how to treat, and how much to treat…. We propose to replace the single risk factor–based approach with the assessment of global cardiovascular risk, both in the clinical management of individual patients and in guidelines. (Volpe et al., 2004)

Other considerations include major adverse life event and high perceived stress at work or home.

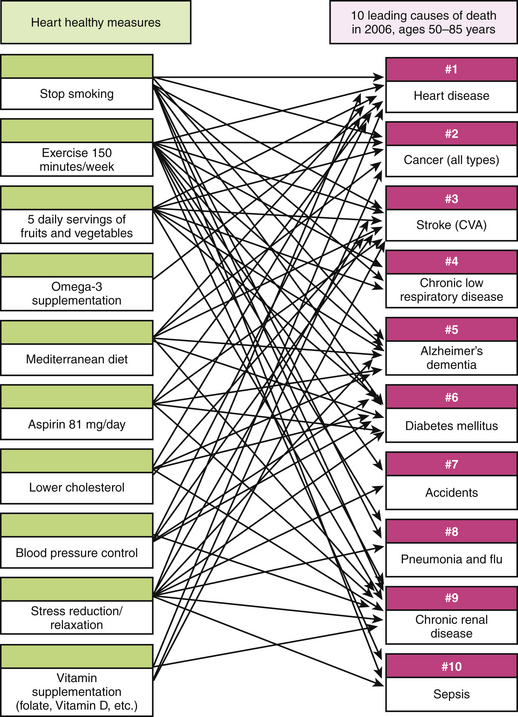

The power of global cardiac risk assessment lies in the synergies achieved with the simple medical interventions to address increased risk. Figure 7-1 illustrates how a single-intervention health promotion program using only “CAD Risk Assessment” and the appropriate conservative responses previously listed achieve multiple synergistic benefits across a large spectrum of diseases and the 10 leading causes of death.

Primary Prevention: A Focus on Lifestyle

A clinical practice may choose a broad, primary prevention approach rather than a single focus on prevention of coronary heart disease. Between 2000 and 2009, nine major studies demonstrated that a healthy lifestyle is associated with large reductions in all-cause mortality and major reductions in multiple disease-specific outcomes. These studies succinctly define what should be understood by the term “healthy lifestyle.” These primary prevention studies demonstrate that persons who have a number of healthy characteristics at the beginning of a period of observation enjoy remarkable benefits over periods ranging from 4 to 20 years.

The results of these studies are summarized in Tables 7-3 and 7-4. Despite minor variations, there is now substantial consensus on what constitutes a “healthy lifestyle.” Briefly stated, a healthy lifestyle consists of the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree