Chapter 35 Lateral and Medial Epicondylitis

Introduction

In continental Europe, the term lateral epicondylitis is often used to describe a painful condition affecting the lateral side of the elbow, more specifically, the origin of the extensors of the wrist. It was first described by Runge in 1873 as ‘Schreibers Krampfes’ (writers cramps), although the name used in the English literature was ‘lawn tennis elbow’, coined by Morris in 1882.1,2

Initially seen as an occupational disease, not necessarily only in tennis players, treatment has focused on changing habits and practices at work or in the case of tennis players properly determine racket grip diameter. Initially overuse, especially repetitive forearm activity and wrist extension, was felt to lead to the development of tendinosis and the formation of granulation tissue in an attempt to repair the damaged extensor tendon origin. More recently, however, literature has focused on the condition being a degenerative tendinopathy of the extensors of the wrist and fingers.3–5

Although lateral epicondylitis is a very common condition, knowledge about its incidence and prevalence is limited. The incidence of lateral epicondylitis in the general population is reported to be 0.6%6 as against 9% in tennis players.7 Prevalence is reported as being between 1% and 3% in the general population8 and 14% in tennis players depending on the age.7 However, one might suspect that with the increased use of computers in day-to-day life, these rates may have risen.

Background/aetiology

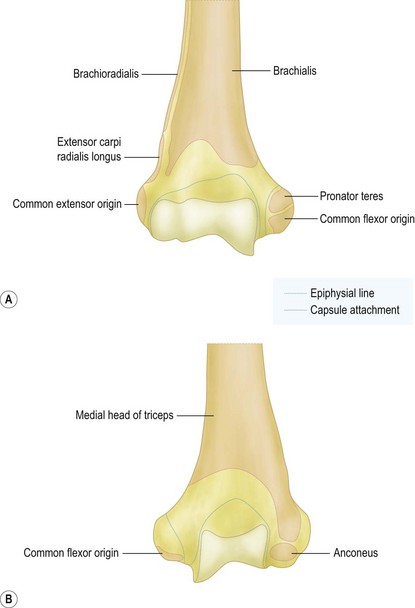

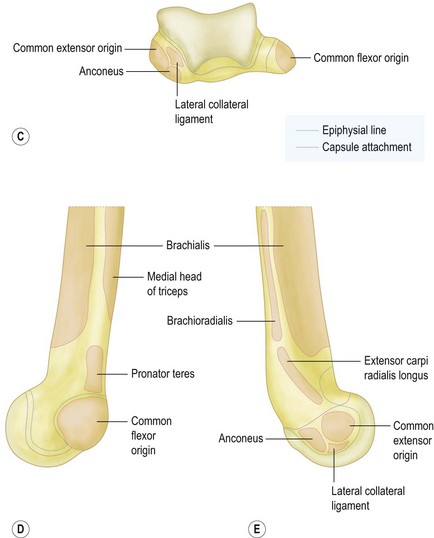

The lateral humeral epicondyle has the origin of the anconeus muscle on its posterior surface, and of both the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) and the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) on its anterior surface. The extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and the brachioradialis have a more proximal origin on the anterior aspect of the supracondylar ridge. The common extensor origin consists of the ECRB and the EDC. Degeneration of this tendon usually occurs within the superior deep fibres (Fig. 35.1).

5 – extensor carpi radialis longus

(Redrawn with permission from A Colour Atlas of Human Anatomy, RMH McMinn and RT Hutchings, Wolfe Medical Publications, London.)

There is some dispute about the origin of the pain in lateral epicondylitis. It is, however, likely to be multifactorial. The existence of free nerve endings in the aponeurosis and granulation tissue around the lateral epicondyle was shown by Goldie et al. In addition, biochemical analysis revealed the presence of substance P receptors within the extensor origin and increased levels of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate in patients with epicondylitis lateralis.9–11 These findings do not directly connect the pain to the lateral epicondylitis, but they do explain the excellent early results of corticosteroid injections into the common extensor tendon origin. In addition, a substantial number of so-called tennis elbow cases have intra-articular abnormalities (11–69%). These include, synovial plicae, synovitis and lateral cartilage degeneration. Indeed the presence of these additional pathologies have led proponents of arthroscopic treatment to recommend this technique.4,12–14

Stage 4: Injury exhibits the features of a stage 2 or 3 injury and is associated with other changes such as fibrosis, soft matrix calcification and hard osseous calcification. The changes that are associated with a stage 4 injury also may be related to the use of cortisone.3

In practice, it is the second stage (angiofibroblastic degeneration) that is most commonly associated with sports-related tendon injuries such as tennis elbow and with overuse injuries in general. Within the tendon, there is a fibroblastic and vascular response (tendinosis) rather than an immune blood cell response (inflammation). Thus, the terms epicondylitis and tendinitis are misnomers. Finally he also postulated that some patients who have tennis elbow may have a genetic predisposition that makes them more susceptible to tendinosis at multiple sites. He termed this condition ‘mesenchymal syndrome’ on the basis of the stem cell line of fibroblasts and the presence of a potentially systemic abnormality of cross-linkage in the collagen produced by the fibroblasts. Patients may have mesenchymal syndrome if they have two or more of the following conditions: bilateral lateral tennis elbow, medial tennis elbow, cubital tunnel syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, trigger finger or rotator-cuff tendinosis.3

Traditionally we are taught that symptoms will get better with time: approximately 80% of patients with newly diagnosed lateral epicondylitis report symptomatic improvement at 1 year.15–18 A lesser degree of residual symptoms are, however, not unusual. Finally only 4–11% of patients seek further medical treatment or surgical intervention.4,15,18–20

Poor prognostic factors for obtaining success with non-surgical treatment were identified by Haahr and Andersen and included manual labour, dominant arm involvement, long duration of symptoms with high base line pain levels and poor coping mechanisms.16

Shiri et al described the risk factors for lateral and medial epicondylitis. Smoking or former smoking behaviour was strongly associated with both lateral and medial epicondylitis in their study of 4783 patients in Finland. Also physical load factors, smoking and obesity were strong determinants of epicondylitis.21

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

Presentation

If the degenerative involvement of the ECRB origin is sufficient to compromise the load-bearing capacity of the ECRB tendon, load transfer to the EDC portion of the conjoint tendon may occur. Rarely, even the posteriorly located ECU tendon may also be involved. In these cases involvement of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL) may occur with resulting posterolateral instability as a sequel. Posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) involvement may reflect the anatomical proximity of the supinator tendon origin on the deep surface of the ECRB tendon and the secondary changes in the arcade of Frohse, which also originates on this tendon. In cases of radial nerve impingement (radial tunnel syndrome) under the arcade of Frohse, pain is usually concentrated more distally and resisted extension may not be painful, whereas resisted extension of the thumb and the index finger will. In addition, resisted forearm supination may be painful, something which is usually not the case in patients with lateral epicondylitis. However, in 5% of patients, it is said that both conditions can coexist.22 Verhaar and Spaans studied a number of patients with supposedly radial tunnel syndrome. They found that in 14 out of 16 cases there was no evidence of PIN compression on electromyography (EMG). As a consequence they concluded that these data did not support the hypothesis that the signs and symptoms of the majority of cases diagnosed as radial tunnel syndrome are caused by compression of the PIN.23

Investigations

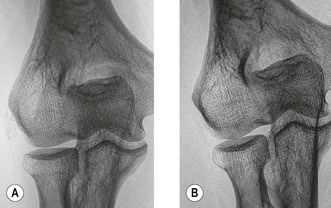

Lateral and medial epicondylitis are essentially a clinical diagnosis. Although additional investigations can be useful to confirm the diagnosis or indeed exclude other conditions. Radiographic examination can reveal small areas of calcification over the lateral epicondyle of the humerus indicating a calcific tendinopathy. Nirschl and Pettrone reported 22–25% of these calcifications in patients with tennis elbow4 (Fig. 35.2). Usually however, radiographs are normal. Tendinopathy of the extensors of the wrist can be visualized by sonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the latter being more expensive, the former being more operator dependent. Ultrasound investigation visualizes focal hypoechoic areas and intrasubstance tears, as well as peritendinous fluid and thickening of the common extensor tendon.24 Sensitivity is reported to be 64–88% for evaluation of the common extensor origin architecture, but specificity is quite variable (36–100%), depending on the study25,26 (Fig. 35.3).

MRI can also be used for the investigation of suspected intra-articular abnormalities, the intactness of the radial collateral ligament complex as well as the extent of any tear or disease in the common extensor tendon. In 90% of patients, oedema is present within the tendon. It should, however, be noted that oedema has also been seen in 14–54% of asymptomatic patients. Finally the increased T2 signal may persist for weeks after the symptoms have resolved.27–30

Treatment options

Boyer and Hastings in 1999 appealed for better evidence in treating tennis elbow. An examination of the literature can only lead us to believe that most, if not all, common non-operative therapeutic modalities used for the treatment of tennis elbow are unproven at best or costly and time-consuming at worst. Most of the published literature on the non-operative treatment of patients with lateral tennis elbow consists of poorly designed trials. The selection criteria are nebulous, the control group is questionably designed, and the number of patients is often too low to avoid a serious loss of study power. These studies therefore have a high beta error, implying an inability to detect a difference between groups, even if one truly existed. If clinical signs and symptoms persist beyond the limit of acceptability of both patient and surgeon, then an array of surgical options are available. These range from a 10-minute office procedure (percutaneous release of the extensor under local anaesthesia) to an extensive joint denervation, in which all radial nerve branches ramifying to the lateral epicondyle are directly or indirectly divided. How is the surgeon to choose, given the fact that most of the published surgical studies are case series of one type of operation or another, consisting of patients operated on and evaluated by the same authors.31 In 2007, Cowan et al repeated the cry for good clinical research into the treatment of lateral epicondylitis; very little progress being made in the last 10 years!32 As a consequence, while the complete spectrum of treatment will be discussed, it is important to realize that there is little if any hard evidence that one is more effective than another.

In 2006, Bisset et al concluded that physiotherapy combining elbow manipulation and exercise has a benefit over no treatment in the first 6 weeks and to corticosteroid injections after 6 weeks, providing a reasonable alternative to injections in the mid to long term. The significant short-term benefits of corticosteroid injection were paradoxically reversed after 6 weeks, with high recurrence rates, implying that this treatment should be used with caution in the management of tennis elbow.33

Comparing all different treatment options one must consider the natural course of lateral epicondylitis. Hay et al described the effects of corticosteroid injections, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and a placebo at 4 weeks (92%, 57% and 50% success rate, respectively) and after 12 months (84%, 85% and 82% success rate, respectively) suggesting a benign natural course.34

Supposedly a biomechanically active counter-force brace or ‘tennis elbow strap’ aims to reduce strain at the elbow epicondyle, to limit pain provocation and to protect against further damage. Struijs et al were not able to demonstrate a difference in outcome between patients treated by physiotherapy, a brace or with a combination of both.35 Other treatments with limited scientific support include: pulsed ultrasound to break up scar tissue, promote healing and increase blood flow in the area; extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT); the injection of botulinum toxin; sclerotherapy; acupuncture and trigger point therapy. Based on a systematic review of nine placebo-controlled trials involving 1006 participants, there is ‘platinum’-level evidence that shock wave therapy provides little or no benefit in terms of pain relief or improved function in lateral elbow pain. There is ‘silver’-level evidence based on one trial involving 93 participants that steroid injection may be more effective than ESWT.36

Placzek et al reported on the use and effects of botulinum toxin in lateral epicondylitis, however, although the results were good at 18 weeks after injection, no longer term report exists. Also the side effects of decreased wrist and third finger extension remains an issue of concern.37 Conversely, Keizer et al compared surgery with an injection with botulinum toxin reporting results two years after treatment; 15 patients in the botulinum toxin group (75%) had good to excellent results, whereas 17 patients in the operative group scored good to excellent (85%). When analysed with an overall scoring system, however, no differences were found between the two forms of treatment.38 Finally, Hayton et al in 2005 reported the results of a double-blind randomized effective study in botulinum toxin type A against a normal saline placebo for the treatment of chronic tennis elbow. Three months after injection, there was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to grip strength, pain or quality of life. As a consequence they concluded that there was no evidence for any benefit from botulinum toxin injections in treatment for this condition.39

Edwards and Calandruccio reported that after autologous blood injection therapy 22 patients (79%) in whom non-surgical modalities had failed were relieved completely of pain even during strenuous activity. Mishra and Pavelko described at final follow-up of more than 2 years after injection of buffered platelet-rich plasma a 93% reduction in pain. In both these studies, however, the number of patients was too few to obtain sufficient power.40,41

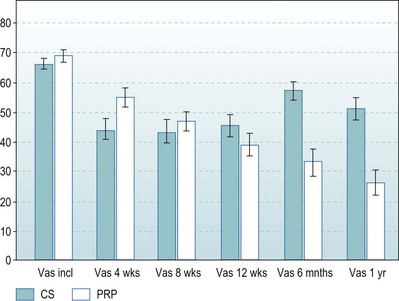

In the Netherlands we performed a prospective randomized, double-blind and multicentred study comparing one injection of corticosteroids with one injection of buffered platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in patient with complaints of lateral epicondylitis for more than 6 months (total of 110 patients, power 0.9). Successful treatment was defined as more than a 25% reduction in visual analogue scale or disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) score without a reintervention after 1 year. The results after 1 year showed that 21 of the 55 patients (40%) in the corticosteroid group and 38 of the 51 patients (75%) in the PRP group were defined as successful with the VAS score; this was significantly different (p < 0.001). Twenty-three of the 55 patients (42%) in the corticosteroid group and 36 of the 51 patients (71%) patients in the PRP group were defined as successful with the DASH, which was also significantly different (p < 0.003)42 (Fig. 35.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree