CHAPTER 10 The knee

Anatomical Features

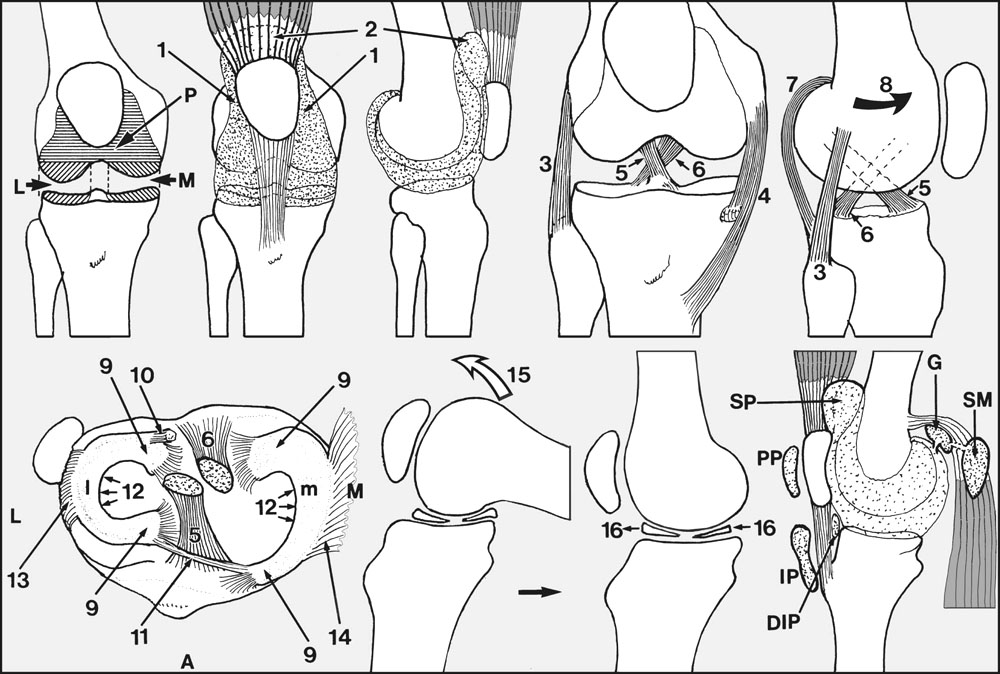

The knee joint (Fig. 10.A) combines three articulations (medial tibiofemoral (M), lateral tibiofemoral (L) and patellofemoral (P)), which share a common synovial sheath; anteriorly, this extends a little to either side (1) of the patella and an appreciable amount proximal to its upper pole (2). This portion, the suprapatellar pouch, lies deep to the quadriceps muscle.

Ligaments

Bursae

Bursal enlargements may be encountered in the popliteal fossa, and these are generally referred to as Baker’s cysts or enlarged semimembranosus bursae. Some are found to communicate with the knee joint (sometimes with a valve-like mechanism), and tend to keep pace in terms of distension with any effusion in the knee.

Extensor Mechanism of the Knee

There are a number of conditions short of disruption which may affect the patellar ligament and its extremities, with the generic title of jumper’s knee. In the Sinding–Larsen–Johansson syndrome, seen in children in the 10–14-year age group, there is aching pain in the knee associated with X-ray changes in the distal pole of the patella. Osgood–Schlatter’s disease (which is often thought to be due to a partial avulsion of the tuberosity) occurs in the 10–16 age group. There is recurrent pain over the tibial tuberosity, which becomes tender and prominent. Radiographs may show partial detachment or fragmentation of the tuberosity. Pain usually ceases with closure of the epiphysis, and the management is usually conservative. In an older age group (16–30) the patellar ligament itself may become painful and tender. This almost invariably occurs in athletes, and there may be a history of giving—way of the knee. CT scans may show changes in the patellar ligament, which becomes expanded centrally. Exploration and incision of the patellar ligament is usually advised. Rarely, pain and tenderness may occur proximal to the upper pole of the patella in quadriceps tendinitis.

Ligaments of the Knee

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament

When the tear is acute and accompanies a meniscal lesion, the meniscus is preserved if at all possible to reduce the risks of tibial subluxation and secondary osteoarthritic change, although the damage may be such that excision cannot be avoided. After attention to the meniscus, many would then advocate direct repair of the anterior cruciate ligament, supplemented by a ligament reinforcement or a reconstruction procedure (e.g. using part of the patellar ligament and its bony attachments). When an acute anterior cruciate tear is associated with damage to the medial or, less commonly, the lateral collateral ligament, a similar approach may be employed.

Rotatory Instability of the Knee: Tibial Condylar Subluxations

Where symptoms are demanding, and when a firm diagnosis has been established, the stability of the joint may be restored by an appropriate ligamentous reattachment or reconstruction procedure.

Lesions of the Menisci

Cysts of the Menisci

Ganglion-like cysts occur in both menisci, but are much more common in the lateral. Medial meniscus cysts must be carefully distinguished from ganglions arising from the pes anserinus (the insertion of sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus). In true cysts there is often a history of a blow on the side of the knee over the meniscus. They are tender, and as they restrict the mobility of the menisci they render them more susceptible to tears. They are generally treated by excision, and sometimes simultaneous meniscectomy may be required, especially if there are problems with recurrence. Some workers believe that all meniscal cysts have an associated tear, and prefer to deal with the problem by arthroscopic resection of the tear and simultaneous decompression of the cyst through the substance of the meniscus.

Patellofemoral Instability

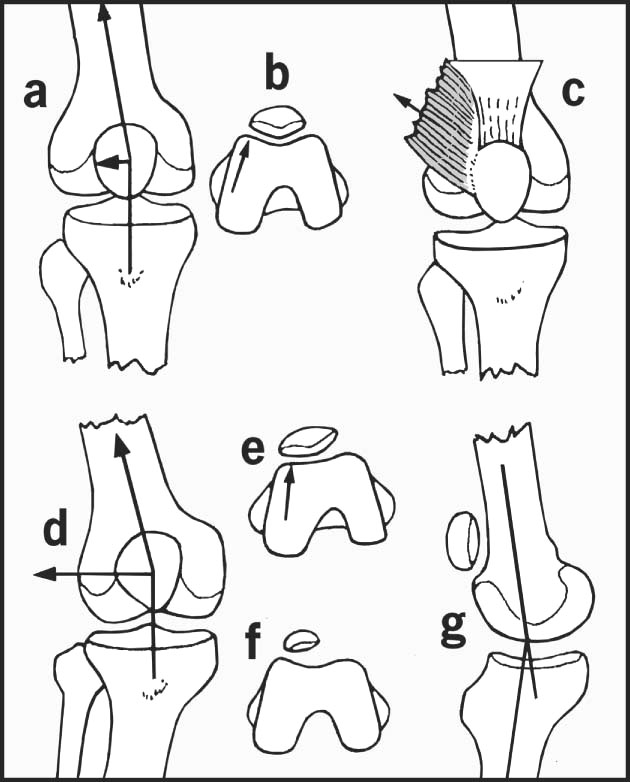

The patella has always a tendency to lateral dislocation as the tibial tuberosity lies lateral to the dynamic axis of the quadriceps (Fig. 10.B); any tightness in the extensor mechanism (e.g. from quadriceps contractions or fibrosis) generates a lateral component of force that tends to displace the patella laterally. Normally, at the beginning of knee flexion the patella engages in the groove separating the two femoral condyles (the trochlea), and this keeps it in place as flexion continues. This system may be disturbed in a number of ways. The side thrusts that tend to cause the patella to sublux laterally may be increased by an abnormal lateral insertion of the quadriceps, tight lateral structures, or by increases in the angle between the axis of the quadriceps and the line of the patellar ligament (e.g. as a result of knock-knee deformity, or by a broad pelvis). The lateral condyle which supports and guides the patella may be deficient, or the patella itself may be small and poorly formed (hypoplasia). If the patella is highly placed (patella alta) it may fail to engage in the condylar groove at the beginning of flexion. (This condition is often associated with genu recurvatum.) Medial to the patella the soft tissues that would normally help prevent an abnormal lateral excursion of the patella may be deficient, sometimes as a result of stretching from previous dislocations.

There are a number of conditions characterised by loss of normal patellar alignment.

Habitual dislocation of the patella

The patella dislocates every time the knee flexes, and this is pain free. It often arises in childhood and may be due to an abnormal attachment of the iliotibial tract. In a number of cases in the neonatal period it results from fibrosis in a quadriceps muscle which has been used for intramuscular injections. The condition also occurs in joint laxity syndromes. In the established case there is usually a severe associated deficiency of the trochlea. It may be treated by extensive lateral releases, medial reefing, and sometimes transposition of the tibial tubercle.

Affections of the Articular Surfaces

Bursitis

Cystic swelling occurring in the popliteal region in both sexes is usually referred to as enlargement of the semimembranosus bursa. In fact, several of the bursae known to the anatomist may be involved, either singly or together. The swelling sometimes communicates with the knee joint and may fluctuate in size. Rupture may lead to the appearance of bruising on the dorsum of the foot, and this may help to distinguish it from deep venous thrombosis or cellulitis. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, or if the swelling is persistent and producing symptoms, excision is advised.

How to Diagnose a Knee Complaint

1. Note the patient’s age and sex, bearing in mind the following important distribution of the common knee conditions (Table 10.1).

| Age group | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| 0–12 | Discoid lateral meniscus | Discoid lateral meniscus |

| 12–18 | Osteochondritis dissecans | First incidents of recurrent dislocation of the patella |

| Osgood–Schlatter’s disease | Osgood–Schlatter’s disease | |

| 18–30 | Longitudinal meniscus tears | Recurrent dislocation of the patella |

| Chondromalacia patellae | ||

| Fat pad injury | ||

| 30–50 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| 40–55 | Degenerative meniscus lesion | Degenerative meniscus lesion |

| 45+ | Osteoarthritis | Osteoarthritis |

Infections are comparatively uncommon and occur in both sexes in all age groups.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree