6 Joint Diseases A multitude of radiologic changes occur in articular disorders. No single radiographic finding is however diagnostic for a specific arthropathy, since individual lesions in many conditions appear similar. The combinations of various radiologic parameters may lead to an accurate diagnosis, especially when pertinent clinical and laboratory findings are taken into consideration. The time and sequence of arthritic abnormalities observed with respect to the evolution of the disease may also offer important clues to the correct diagnosis. For example a rapidly progressing, destructive arthritic process involving a single joint is virtually diagnostic for septic (pyogenic) arthritis. Certain diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis show radiologic manifestations in a relatively early phase. Other arthritides such as gout depict radiographic abnormalities only late in their clinical course. Proper radiographic analysis of any arthropathy must include the following criteria: 1. Number of joints involved (monoarticular versus polyarticular). 2. Distribution pattern of involved joints. 3. Joint space width. 4. Erosion. 5. Subchondral cysts. 6. Fragmentation of subchondral bone and loose intra-articular bodies. 7. Reactive (productive) bony changes (subchondral sclerosis, osteophytosis, enthesopathy, periostitis). 8. Osteoporosis (periarticular or generalized). 9. Joint deformities. 10. Chondrocalcinosis and periarticular soft tissue calcifications. 11. Joint effusions and para-articular soft tissue abnormalities. An arthritic process involving a single joint is commonly found in infectious arthritis, gout, secondary osteoarthritis and avascular necrosis. In pyogenic and tuberculous arthritis joint space narrowing, joint effusion and periarticular osteoporosis are characteristically present in the early stage followed by poorly defined bone destruction. Since periarticular osteoporosis and joint space narrowing are not present in gout, osteoarthritis and avascular necrosis, every monoarticular disease depicting these two radiographic abnormalities must be considered infectious in origin until proven otherwise. Osseous erosions and cysts in gout are sharply marginated as opposed to the poorly defined bone destruction in infectious arthritis. Osteoarthritis secondary to trauma may at times be difficult to differentiate from gout in small joints without proper clinical history and laboratory findings, since osseous erosions may simulate post-traumatic defects. Avascular necrosis in the early stage presents with normal radiographic findings. Subsequently patchy lucent and sclerotic areas may be seen in the subchondral bone on one side of a joint, followed by a diagnostic arc-like subchondral lucency (crescent sign) and eventually fragmentation and collapse of the involved bone. Rheumatoid arthritis, seronegative spondylarthropathy (psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis and enteropathic arthropathy), gout, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease (CPPD), osteoarthritis and neuropathic arthropathy are the most common polyarticular joint disorders. A symmetrically distributed articular disorder presenting with concentric joint space loss, erosions, osteoporosis, and fusiform soft tissue swelling is characteristic for rheumatoid arthritis. An erosive arthritis process involving both synovial and fibrocartilagenous joints (e.g. pubic symphysis and manubriosternal joints) and the ligamentous attachments in the pelvis, femur and calcaneus in an often asymmetric fashion is characteristic for a seronegative spondylarthropathy. This diagnosis is further supported by the absence of osteoporosis, the presence of bony proliferation and intra-articular osseous fusion, and involvement of the spine and sacroiliac joints. Gouty arthropathy is characterized by asymmetric involvement of the appendicular skeleton, eccentric osseous erosions, bony proliferation, preservation of the joint space and absence of osteoporosis. In CPPD articular and periarticular calcifications are combined with joint space narrowing, eburnation, cyst formation, fragmentation and collapse. The presence of significant osteophytosis and the general absence of both intra-articular and extra-articular calcifications differentiates osteoarthritis from CPPD. Otherwise the radiographic findings in these two disorders are very similar, though fragmentation and bone collapse are less common in osteoarthritis. Neuropathic osteoarthropathy in an early stage may resemble osteoarthritis and CPPD, but extensive sclerosis associated with joint fragmentation, fractures and subluxations/dislocations is virtually diagnostic in a more advanced case. Table 6.1 Monoarticular disease

Monoarticular arthritis (Table 6.1)

Polyarticular arthritis (Table 6.2)

Infectious arthritis: |

pyogenic |

tuberculous |

fungal |

Gout |

Hydroxyapatite deposition disease (HADD) |

Traumatic arthritis |

Secondary osteoarthritis |

Avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis) |

Pigmented villonodular synovitis |

Synovial osteochondromatosis |

Osteochondritis dissecans |

Table 6.2 Polyarticular disease

Osteoarthritis |

Erosive osteoarthritis |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

Psoriatic arthritis |

Reiter’s syndrome |

Ankylosing spondylitis |

Gout |

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease (CPPD) |

Hemochromatosis |

Ochronosis |

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis |

Hemophilia |

Acromegaly |

Jaccoud’s arthritis |

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

Scleroderma |

Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia |

Table 6.3 Distribution patterns of polyarticular diseases

Involvement | Disease |

Bilateral symmetric | Primary ostearthritis Erosive osteoarthritis Rheumatoid arthritis Ankylosing spondylitis CPPD Hemochromatosis Ochronosis Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis Neuropathic osteoarthropathy Hemophilia Acromegaly Jaccoud’s arthritis Systemic lupus erythematosus Scleroderma Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia |

Asymmetric | Secondary osteoarthritis Psoriatic arthritis Reiter’s syndrome Gout |

Distal interphalangeal joints (hand) | Osteoarthritis Erosive osteoarthritis Psoriatic arthritis Gout Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis Scleroderma |

Proximal interphalangeal joints (hand) | Osteoarthritis Erosive osteoarthritis Rheumatoid arthritis Psoriatic arthritis Gout Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis Scleroderma |

Metacar- pophalangeal joints | Secondary osteoarthritis Rheumatoid arthritis Gout CPPD Hemochromatosis Jaccoud’s arthritis Systemic lupus erythematosus |

First carpometacarpal joint | Osteoarthritis Rheumatoid arthritis Gout Systemic lupus erythematosus |

Common carpometacarpal joint Midcarpal joint | Rheumatoid arthritis Gout Osteoarthritis (scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal joint) Rheumatoid arthritis (including triquetropisiform joint) Gout CPPD (scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal joint) |

Radiocarpal joint | Secondary osteoarthritis Rheumatoid arthritis Gout CPPD Hemochromatosis |

Distal radioulnar joint | Rheumatoid arthritis Gout Scleroderma |

Distribution patterns of articular diseases (Table 6.3)

Symmetric joint involvement is typical of rheumatoid arthritis, primary osteoarthritis, CPPD and neuropathic arthropathy, whereas an asymmetric distribution of the affected joints favors the diagnosis of a seronegative spondylarthropathy, secondary osteoarthritis and gout.

In the hand nonerosive arthritic changes involving the distal interphalangeal joints suggests osteoarthritis, whereas erosive arthritic changes in the distal interphalangeal joints are common in psoriatic arthritis, erosive osteoarthritis and gout. Involvement of the proximal interphalangeal joints is common in rheumatoid arthritis and all aforementioned conditions affecting the distal interphalangeal joints. CPPD does not affect the interphalangeal joints, but has a predilection for the second and third metacarpophalangeal joints and the radiocarpal joint. Involvement of the metacarpophalangeal joints is common in both rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, but these joints are usually spared by both primary and erosive osteoarthritis.

In the wrist erosive arthritic changes without site predilection are very common in rheumatoid arthritis and gout and less frequent in psoriatic arthropathy. Both primary osteoarthritis and CPPD have a predilection for the first carpometacarpal joint and the joint between the scaphoid and trapezium-trapezoid.

In the foot primary osteoarthritis is typically located in both the first metatarsophalangeal joint (hallux rigidus), where it may be associated with hallux valgus deformity, and in the first tarsometatarsal joint. Rheumatoid arthritis commonly affects the interphalangeal joint of the great toe, both the metatarsal-phalangeal and tarsometatarsal joints, the talonavicular and the posterior subtalar joints. Seronegative arthropathies potentially affect any joint of the forefoot, but the most severe changes commonly occur in the metatarsophalangeal joints and the interphalangeal joint of the great toe. Gout shows a predilection for the first metatarsophalangeal joint and to a lesser degree the interphalangeal joint of the great toe, the metatarsophalangeal joints 2 to 5 and the tarsometatarsal joints, although any joint in the forefoot and midfoot can be affected. Neuropathic arthropathy in diabetes may involve the metatarsophalangeal joints and all joints of the midfoot and hindfoot.

Arthritic involvement of the calcaneus most commonly affects the sites of insertion of the Achilles tendon posteriorly and the plantar aponeurosis (fascia) inferiorly, as well as the posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneus that abuts the retrocalcaneal bursa. Retrocalcaneal bursitis leads to unilateral or bilateral erosions at this site in rheumatoid arthritis. Localized retrocalcaneal bursitis not related to a systemic arthritic process is termed Haglund’s syndrome (Fig. 6.1). The condition is aggravaled by a prominent bony protuberance at the posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneus (Haglund’s deformity). The hallmark of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies are fluffy periostitis about the posterior and inferior aspect of the calcaneus and broadbased spurs (entesophytes) at the attachment of the Achilles tendon and plantar aponeurosis (Fig. 6.2). Erosions at these sites as well as near the retrocalcaneal bursa are not a dominant radiographic feature in these conditions. In osteoarthritis well-defined and typically narrow-based calcaneal spurs are found at the osseous tendon attachments. Similar bony excrescenses are associated with acromegaly, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) and CPPD (Fig. 6.3). In the latter condition linear calcific deposition in the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia may also be present. In gout tophaceous nodule in and about the Achilles tendon can lead to erosion near its calcaneal insertion.

In the knee bilateral and symmetric involvement of all three compartments (medial and lateral femorotibial space and patellofemoral joint) with marked joint space narrowing, osteoporosis and erosions is virtually diagnostic of rheumatoid arthritis. A tricompartmental distribution may also be found in seronegative spondylarthropathies, but the involvement is frequently asymmetric and less severe than in rheumatoid arthritis and periosteal new bone formation may be pronounced. In osteoarthritis the medial compartment is typically more severely affected than the lateral compartment resulting frequently in varus deformity. Significant degenerative changes in the patellofemoral joint may be associated. The compartmental distribution of CPPD in the knee is similar to osteoarthritis, but there is no preferential involvement of the medial compartment and both extensive chondrocalcinosis and rapid progression of the arthritic process including osseous destruction and fragmentation favor the former diagnosis. Isolated degenerative-like arthropathy of the patellofemoral joint should also raise the possibility of CPPD. Neuropathic arthropathy is characterized by disorganization of one or both knees including subluxation, fragmentation and extensive sclerosis.

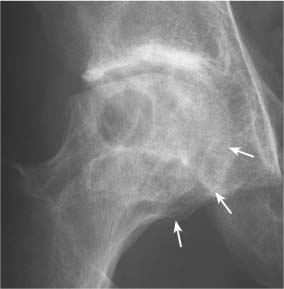

In the hip the pattern of joint space loss may be useful to differentiate various articular diseases. Circumferential (axial or concentric) loss of joint space leads to migration of the femoral head in axial direction along the axis of the femoral neck (Fig. 6.4). Circumferential loss of joint space is associated with rheumatoid arthritis where both hips are affected in symmetric fashion. A unilateral (monoarticular) concentric loss of joint space suggests an infectious process but is also found with idiopathic chondrolysis of the hip. In ankylosing spondylitis a similar bilateral concentric joint space loss is found as in rheumatoid arthritis, but the presence of osteophytosis, commencing on the superolateral aspect of the femoral head and progressing to a collar about the femoral head-neck junction, is distinctive of the former disorder. Hip involvement in both psoriatic arthritis and Reiter’s syndrome is similar to ankylosing spondylitis but uncommon. In CPPD unilateral or bilateral concentric loss of joint space is associated with sclerosis, osteophytosis, cyst formation and eventually fragmentation of the femoral head. The demonstration of chondrocalcinosis in the acetabular labrum and pubic symphysis further supports the diagnosis of CPPD. Even in advanced cases of osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis) of the femoral head with bony collapse and fragmentation the joint space remains largely preserved. In osteoarthritis the loss of joint space narrowing is limited to the weight-bearing superior aspect of the joint or less frequently, to its medial aspect (Fig. 6.5). Besides the subchondral sclerosis, osteophytosis and cyst formation, cortical thickening or buttressing of the medial femoral neck cortex may also be apparent in this condition. Protrusio acetabuli (see Fig. 6.4) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, osteoarthritis (medial migration pattern), infection, acetabular trauma, Paget’s disease and osteomalacia.

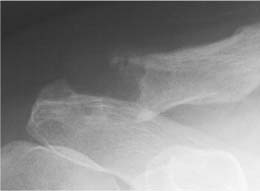

Fig. 6.1 Haglund’s syndrome. Extensive erosive changes in the posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneus are associated with new bone formation and localized soft tissue mass secondary to retrocalcaneal bursitis.

Fig. 6.2 Inflammatory calcaneal spur (enthesophyte). A broad-based plantar calcaneal spur is associated with fluffy periostitis about the posterior and inferior aspect of the calcaneus (Reiter’s syndrome).

Fig. 6.3 Degenerative calcaneal spurs (enthesophytes)). Two well-defined calcaneal spurs depicting cancellous bone outlined by cortical margins are seen at the insertions of the Achilles tendon posteriorly and plantar aponeurosis inferiorly (acromegaly).

Fig. 6.4 Circumferential loss of joint space. Concentric (axial) narrowing of the joint space is associated with tiny articular erosions, extensive fluffy enthesopathy along the ischium and greater trochanter and fused sacroiliac joints. Mild protrusio acetabuli is also present (ankylosing spondylitis).

Fig. 6.5 Asymmetric loss of joint space. Narrowing of the joint space is limited to the superior (weight-bearing area of the hip and is associated with reactive sclerosis and subchondral cyst formation (osteoarthritis).

Fig. 6.6 Hatchet sign. An erosion limited to the lateral aspect of the humeral head (arrows) produces a deformity reminiscent of a hatchet. This finding is typically associated with ankylosing spondylitis or fungal arthritis as in this case. It should not be confused with a Hill-Sachs defect secondary to an anterior shoulder dislocation. Loose intra-articular bony fragments (arrowheads) and a decreased distance between humeral head and inferior aspect of the acromion indicating a chronic rotator cuff tear are also seen.

Fig. 6.7 Milwaukee shoulder. Cloud-like calcification in the rotator cuff and subacromial bursa projecting between the distal acromion and humeral head are associated with destructive shoulder arthritis and chronic rotator cuff tear evident by the decreased distance between humeral head and inferior aspect of the acromion.

In the shoulder region bilateral symmetric loss of joint space in the glenohumeral joints combined with widened eroded acromioclavicular joints is characteristic for rheumatoid arthritis. Ankylosing spondylitis presents in similar fashion, but a large bony defect (erosion) on the superolateral aspect of the humeral head, the “hatchet” deformity (Fig. 6.6), the absence of osteoporosis and the presence of bony proliferation about the osseous erosions are clues to differentiate it from rheumatoid arthritis. Severe osteoarthritis in the glenohumeral joint is usually associated with previous trauma or overuse and is therefore most often uni-lateral. Acromioclavicular joint degeneration is frequent in middle-aged and elderly persons and may lead to shoulder impingement syndrome with the development of spurs protruding inferiorly from this joint and the adjacent undersurface of the acromion. In CPPD an advanced degenerative-like process in the glenohumeral joint may be associated with chondrocalcinosis. Calcium hydroxyapatite crystal deposition disease (HADD) presenting initially with cloud-like calcifications in the rotator cuff or subacromial bursa may progress to a destructive arthropathy of the glenohumeral joint with chronic rotator cuff tear, the so-called Milwaukee shoulder syndrome (Fig. 6.7).

Joint space width (Tables 6.4 and 6.5)

Analysis of the width of the joint space may provide important clues in the differential diagnosis of arthritic disorders. In these conditions the joint space may be narrowed, normal or widened. Furthermore joint space narrowing may be symmetric or asymmetric and occur early or late in the disease process. Symmetric joint space loss involving an entire joint early in the disease process is suggestive of an infectious or inflammatory arthritic disorder. An asymmetric joint space narrowing in the large joints of the lower extremity is indicative of osteoarthritis. In this condition subchondral sclerosis usually precedes a radiographically appreciable joint space loss. Advanced erosive or destructive joint disease with relatively well-maintained joint space and asymmetric joint involvement suggests gout and osteonecrosis, respectively. A widened joint space is typically associated with large joint effusions, especially in children, and hemathrosis secondary to trauma, hemophilia or other bleeding disorders. Joint laxity in neuromuscular disorders frequently presents with a widened joint space too. A drooping shoulder (Fig. 6.8) is an inferior “subluxation” of the humeral head caused by either a large hemarthrosis (e.g. in intra-articular proximal humerus fractures), any neurologic or muscular disorder affecting the supporting musculature or any direct injury of the capsule or rotator cuff itself. True subluxations and dislocations typically present also as joint space widening, but in certain projections these conditions may occasionally mimic a joint space narrowing. A considerable widening of the joint space in the fingers and toes can be found in psoriatic arthropathy when severe destruction of the subchondral bone is present. This condition has to be differentiated from sequelae of resection arthroplasties consisting of removal of one or both articular surfaces in an interphalangeal joint. A widened acromioclavicular joint (Fig. 6.9) is a frequent finding in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthropathy, but also encountered in infectious arthritis, traumatic separation, post-traumatic osteolysis (e.g. weight lifters), acromioplasty with resection of the distal clavicle, and hyperparathyroidism.

Erosions (Table 6.6)

Marginal articular erosions at osseous surfaces that do not possess protective cartilage are typical for early rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 6.10). The erosions typically are poorly defined and without sclerotic margin. In the hand and wrist symmetric involvement with predilection for the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints, trapezium, capitate, scaphoid, triquetrum and pisiform, and both the radial and ulnar styloid is characteristic. A poorly defined monoarticular erosive arthritic process suggests an infectious etiology. In psoriatic arthropathy (Fig. 6.11) marginal erosions characteristically are associated with adjacent bony proliferation evident as irregular excrescences with spiculated appearance. In gout (Fig. 6.12) one or more eccentric erosions with sclerotic margin and over-hanging edge may be evident. In erosive osteoarthritis the combination of osteophytosis and sharply marginated erosions in central location of the joint are characteristic. Fragmentation of an articular surface (e.g. in CPPD, osteonecrosis or secondary to trauma) may result in a defect that can mimic a true erosion (fig. 6.13).

Table 6.4 Narrowed joint space

Osteoarthritis (often asymmetric in weight-bearing joints) |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

Psoriatic arthritis |

Reiter’s syndrome |

Ankylosing spondylitis |

CPPD |

Hemochromatosis |

HADD |

Ochronosis |

Infectious arthritis |

Hemophilia |

Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia |

Endstage of any arthritic process |

Subluxation or dislocation (congenital, traumatic) |

Hemarthrosis or large joint effusion |

Joint laxity (neuromuscular, traumatic) |

Psoriasis |

Neuropathic osteoarthropathy |

Acromegaly |

Pigmented villonodular synovitis |

Synovial osteochondromatosis |

Synovial neoplasm |

Resection arthroplasty |

Fig. 6.8 Drooping shoulder. A large lipohemarthrosis with fat-blood level (arrows) secondary to a nondisplaced greater tuberosity fracture produces inferior subluxation of the humeral head evident by the increased distance between the latter and the inferior aspect of the acromion.

Fig. 6.9 Widening of the acromioclavicular joint is caused by erosion of the distal clavicle and to a lesser degree the distal acromion (secondary hyperparathyroidism).

Fig. 6.10 Erosions in rheumatoid arthritis. Multiple preferentially marginal erosions with symmetric distribution and characteristic localization (sparring of the distal interphalangeal joints) are seen.

Fig. 6.11 Erosions in psoriatic arthritis. Multiple marginal erosions are associated with extensive bony proliferation evident as irregular excrescences with spiculated appearance. Note also the involvement of the distal interphalangeal joints and the partial resorption of the tufts on the third and fourth finger.

Fig. 6.12 Erosions in gout. Eccentric erosions with overhanging edge (arrow) and associated soft tissue mass is seen about the distal interphalangeal joint.

Fig. 6.13 Fragmentation of the articular surface in frostbite. Fragmentation of the distal articular surfaces of the proximal phalanx of the fifth finger and middle phalanx of the fourth finger secondary to osteonecrosis is seen. The remaining less exposed fingers were intact.

Erosive osteoarthritis |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

Psoriatic arthritis |

Reiter’s syndrome |

Ankylosing spondylitis |

Gout |

HADD |

Amyloidosis |

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis |

Infectious arthritis |

Scleroderma |

PVNS (pressure erosions) |

Synovial osteochondromatosis (pressure erosions) |

Articular defects simulating erosions in CPPD, osteonecrosis, osteochondritis dissecans and osteochondral fractures |

Subchondral cysts (Table 6.7)

Single or multiple radiolucent lesions with sclerotic margins are commonly found with osteoarthritis, CPPD, and osteonecrosis (Fig. 6.14). In both osteoarthritis and osteonecrosis these cysts are typically located within the pressure segment of the joint, whereas in CPPD they are more widespread and frequently unusually large. A subchondral cyst occasionally is the sequela of a bone injury that becomes evident over a period of months after the traumatic episode (traumatic cyst). In rheumatoid arthritis the subchondral cysts frequently originate in the chondro-osseous junction and do not depict a surrounding sclerotic margin. An intraosseous ganglion presents as a solitary subchondral cystic lesion with sclerotic margin anywhere in the subchondral bone of a joint not affected by an arthritic process. Furthermore subchondral cysts can be mimicked by intraosseous gouty tophus, a Brodie’s abscess and variety of neoplasms (e.g. chondroblastoma, giant cell tumor, intraosseous lipoma, clear cell chondrosarcoma, and skeletal metastases).

Fragmentation of subchondral bones and loose intra-articular bodies (Tables 6.8 and 6.9)

Fragmentation of the articular surface (Fig. 6.15) is commonly associated with CPPD, osteonecrosis, neuropathic arthropathy, far advanced osteoarthritis, and trauma (osteochondral fractures) resulting frequently in one or more loose intra-articular bodies. Detached osteophytes in osteoarthritis may also lead to loose intra-articular bodies. Joint destruction secondary to pyogenic or tuberculous arthritis may also be associated with loose intra-articular bony fragments. In osteochondritis dissecans the solitary osteochondral fracture fragment may be still located in the original articular defect (pit) or freely mobile in the joint. In synovial osteochondromatosis a large number of calcified/ossified loose bodies located within and around the involved joint and ranging in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters is characteristic.

Reactive (productive) bony changes

In osteoarthritis of weight-bearing joints sclerosis of the subchondral bone is frequently the first radiographic sign of the disease, since the causative joint cartilage degeneration can only be appreciated when a substantial loss of cartilage has occurred resulting in joint space narrowing.Osteophytosis (Fig. 6.16) is the hallmark of primary and secondary degenerative joint disease.Marginal osteophytes develop in the periphery of the articular surface of a joint and appear as lips of new bone. Less common are central (interior joint) osteophytes appearing as button-like or flat bony excrescences that may be demarcated at their bases by remnants of the original cartilage simulating occasionally loose intra-articular bodies.

Fig. 6.14 Subchondral cyst in avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis). A cystic lesion with sclerotic margin is seen in the weight-bearing portion of the deformed and flattened femoral head. Secondary degenerative changes including remodeling and new bone formation (buttressing) along the medial aspect of the femoral head and neck (arrows) are also evident in this patient with sickle cell disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree