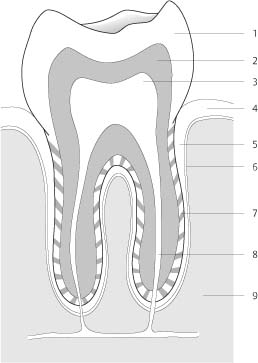

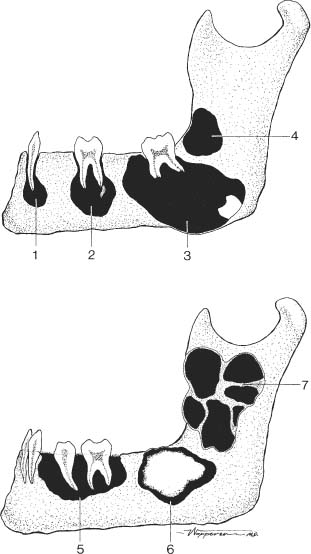

11 Jaws and Teeth Calcifications in the soft tissues around the jaws may be caused by the same conditions as anywhere else in the body. They are commonly arteriosclerotic in origin or due to calcified lymph nodes secondary to granulomatous disease. These conditions must, however, be differentiated from salivary gland calcifications, which are usually caused by salivary calculi. They are radiopaque in approximately 80% because of their high calcium carbonate content and occur most often in the submandibular glands, less commonly in the parotid glands, and virtually never in the sublingual glands. A salivary stone tends to be oval in shape and usually has a relatively homogeneous density (Fig. 11.1). Dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint may affect as many as 25% of the adult population and causes a variety of clinical symptoms ranging from headache to myofascial pain. This entity has gained increasing attention in recent years and is now referred to as temporomandibular joint syndrome. Unfortunately, plain film radiography is generally of little use in evaluating this condition, since in the vast majority of cases the disorder is related to an abnormality of the meniscus that divides this joint, and hence arthrography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging is required for proper diagnosis. In far-advanced cases, flattening or atrophy of the mandibular head, flattening of the articular tubercle, sclerosis, cysts, and spur formations around the joint may be seen with conventional radiographic technique (Fig. 11.2). In the jaws, many pathologic conditions are related to the teeth. The emphasis in the remaining part of this chapter is on the differential diagnosis of these odontogenic lesions. The radiographic presentations of nonodontogenic lesions that may be confused with odontogenic lesions will be briefly discussed. For a more complete differential diagnosis of nonodontogenic lesions, the reader should refer to Chapters 1, 2, and 5. The periodontium represents the supporting structure of the teeth comprising gingiva, periodontal ligament (membrane), alveolar bone, and cementum (Fig. 11.3). Radiographically, the cementum outlining the roots of the teeth cannot be differentiated from dentin. The periodontal membrane, evident radiographically as a radiolucent line of less than 1 mm in width, separates the root of a tooth in its socket from the alveolar bone of the jaw. A thin cortical line, the lamina dura, demarcates the latter from the periodontal membrane. From this observation, it becomes obvious that periodontal pathology can manifest itself radiographically as loss of lamina dura, widening of the periodontal membrane, or both. These subtle changes cannot, however, be appreciated with conventional x-ray technique, and require special dental films with high resolution for proper evaluation. Excessive bone resorption around the root of a tooth is commonly referred to as “floating tooth.” Fig. 11.1 Submandibular gland calculus. An ovoid soft-tissue calcification (arrow) is seen below the right mandibular angle. Fig. 11.2 Advanced degenerative changes in the temporomandibular joint (tomography). Anterior spur and degenerative cyst are seen in the deformed and sclerotic head of the condylar process. There is also considerable flattening of the articular tubercle located anteriorly to the glenoid fossa, with significant sclerosis of both these structures. Resorption of the lamina dura is common in primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism. In this condition, it is usually not associated with an appreciable widening of the periodontal membrane space. Reappearance of the lamina dura occurs after proper treatment. A generalized loss of the lamina dura can also be found with osteoporosis of any etiology (e.g., senile, steroid therapy, Cushing’s syndrome), but in these cases remnants of the lamina can often still be recognized unless the osteoporosis has progressed so far that the correct diagnosis can easily be established by other radiographic findings. In both periodontosis (non-inflammatory, degenerative) and periodontitis (inflammatory), resorption of bone including the lamina dura occurs characteristically around the neck and proximal part of the root of a tooth while the lamina dura around the apex remains intact. If the process proceeds to a periodontal abscess, resorption of the entire lamina dura combined with widening of the periodontal membrane space may be found. Fig. 11.3 Anatomy of a normal molar tooth. 1 Enamel; 2 dentin; 3 pulp; 4 gum; 5 periodontal membrane; 6 lamina dura; 7 cement; 8 apical canal; 9 alveolar bone. Fig. 11.4 Paget’s disease. Thickening and sclerosis of the mandible resulted in an apparent loss of the lamina dura around the teeth. Fig. 11.5 a, b Lytic mandibular lesions. 1 Dental granuloma; 2 periodontal cyst (occasionally containing small root remnant); 3 dentigerous cyst; 4 primordial cyst; 5 “floating teeth” (e.g., eosinophilic granuloma; 6 odontoma); 7 ameloblastoma. The radiographic absence of lamina dura is not only the result of its resorption but may also be caused by an increase in bone density of the adjacent cancellous bone as seen, for example, in sclerosing osteomyelitis. The radiographic loss of lamina dura observed in Paget’s disease (Fig. 11.4), fibrous dysplasia, and osteomalacia is commonly the result of both bone resorption and sclerosis. The width of a normal periodontal membrane space measures radiographically less than 1 mm. Generalized widening of the periodontal membrane space with intact lamina dura is characteristic for scleroderma, but may also be found in patients with the habit of forcibly clenching the teeth. The most common cause for a localized widening of the periodontal gap associated with resorption of the lamina dura is a severe inflammation such as periodontal abscess. More extensive bone resorption around one or several teeth produces radiographically the impression of “floating teeth.” In addition to a periodontal abscess, this finding is common in eosinophilic granuloma (Langerhans cell histiocytosis), but may also be encountered in any other condition producing a large lytic lesion such as ameloblastoma, lymphoma, leukemia, multiple myeloma, metastases, and odontogenic lesions. Localized lytic lesions of odontogenic origin can represent an inflammatory, cystic, or neoplastic process or may be a developmental anomaly. The most common lytic lesions in the mandible are shown schematically in Fig. 11.5, while their more complete differential diagnosis is discussed in Table 11.1. Only a few localized sclerotic lesions are unique for the jaw. Odontomas consist of an irregular opaque mass of different dental tissues such as enamel, dentin and cementum surrounded by a radiolucent line or band representing the fibrous capsule. Symmetric and bilateral sclerotic bony protuberances are occasionally found in the midline of the palate or along the lingual surface of the mandible (primarily in the canine-premolar region) and are termed torus palatinus and mandibularis, respectively. These are benign static growths without clinical significance. They must be differentiated from osteomas, which are protruding mass lesions composed of abnormally dense bone that is formed in the periosteum. They are most common in the skull and facial bones. Table 11.1 Differential Diagnosis of Lytic Lesions in the Jaw

Periodontal Abnormalities

Lesion | Radiographic Appearance | Comments |

Periodontal abscess | Localized poorly to well-defined defect in the periphery of a tooth. | Periodontitis is an extension of gingivitis to the underlying periodontal tissues. An abscess develops usually in a periodontal pocket that is partially or completely occluded, or is occasionally caused by a foreign body lodged in the periodontium. |

Periapical abscess | Localized poorly to well-defined defect around the apex of a tooth. | Results from progression of pulpitis. In the acute stage, the tooth is extremely painful and tender to percussion. In the chronic stage, draining sinuses to the oral cavity, maxillary antra and even the surface of the skin may occasionally develop. |