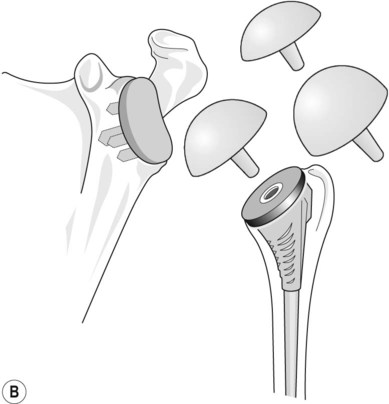

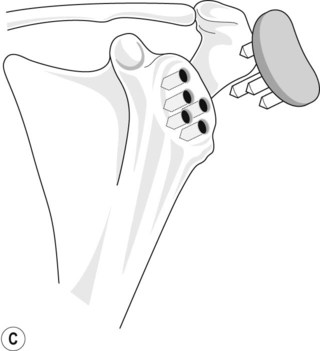

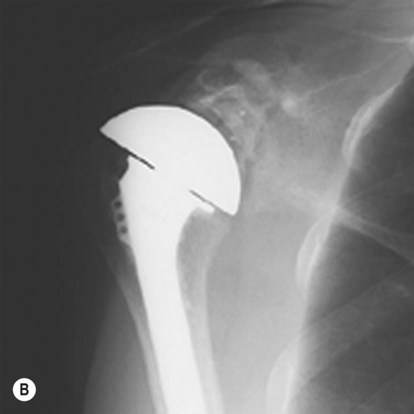

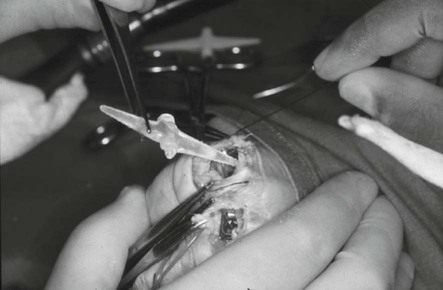

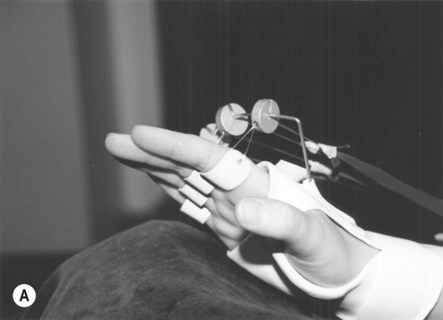

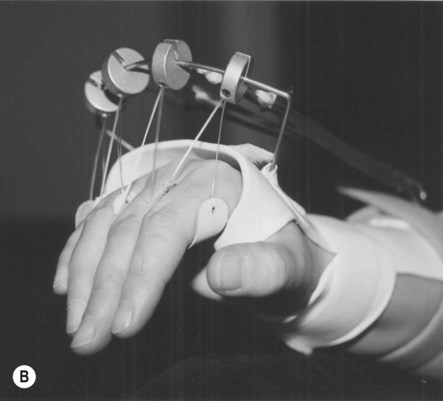

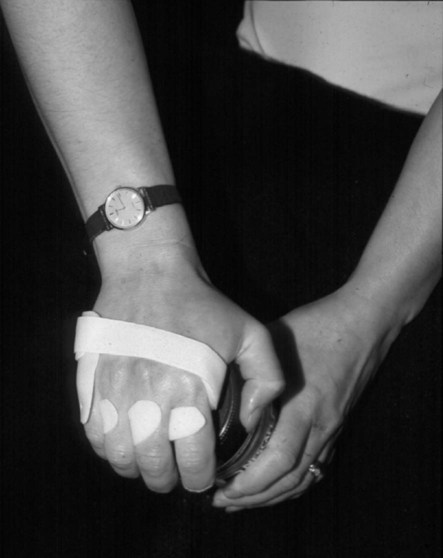

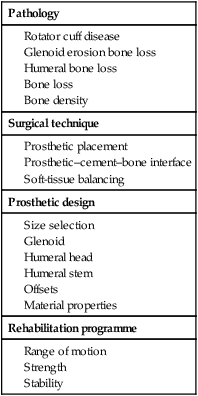

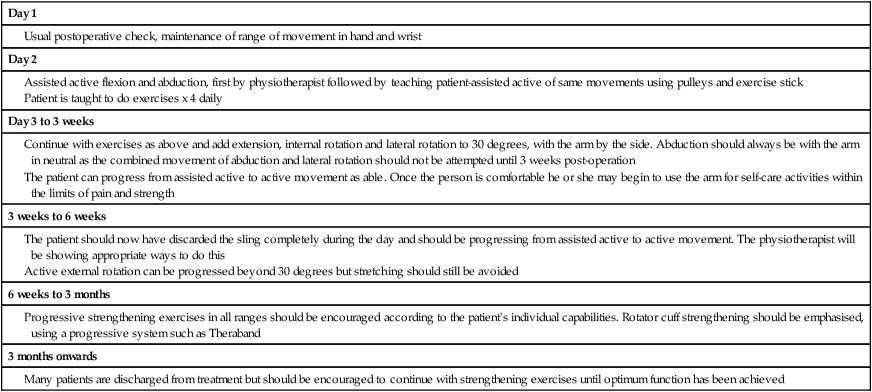

There is no ‘typical’ patient who is appropriate for a joint arthroplasty. As with all modern medicine, a decision has to be made which balances the risks of surgery against the potential improvements. Patient age per se is no longer an acceptable clinical decision-making tool (Brander et al. 1997). Generally, the surgical team promote conservative treatments and optimisation of health until pain or disability is severe enough to cause a significant impact on the person’s quality of life, where surgery would make things significantly better or prevent a major deterioration. Initially developed for the reconstruction of severe proximal humerus fractures, proximal humeral arthroplasty was also used for people suffering from OA, with surprisingly good results. In 1973, Neer redesigned the humeral component and added a glenoid to make the first unconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty. The basis of the design was to produce as near to an anatomical replacement as possible – the principle followed in most modern prostheses (Neer et al. 1982). There are many factors influencing the outcome of shoulder arthroplasty (Iannotti and Williams 1998; see Table 23.1) that physiotherapists need to know about so that realistic rehabilitation goals can be set. Therefore, good communication with the surgical team is very important. Table 23.1 Factors affecting outcome of problematic shoulder reconstruction Table 23.2 shows a typical postoperative protocol; however, these will vary depending upon the surgeon’s preference, any intra-operative changes to the procedure, patient factors and their response. As always, the postoperative regimen must be agreed between the surgeon and the physiotherapy team. Table 23.2 Example of postoperative routine following primary total shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis People with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who undergo shoulder arthroplasty are likely to have a number of the adverse pathological factors (Table 23.1). The expected results will depend on how many, and how severe, they are, so the results are generally not as good as in OA patients. The surgical approach and basic postoperative management are the same. In advanced disease (either OA or RA type) it is not always possible to insert a glenoid component – it is not possible to attach the glenoid component securely enough if there is gross bone loss around the glenoid fossa. Also, if there is a lack of rotator cuff function, the humeral head will ‘rock’ the glenoid component, causing loosening. The problem of glenoid fixation is one of the ongoing dilemmas in shoulder arthroplasty (Figure 23.1 and Figure 23.2). RA can affect any joint in the body, but it is particularly devastating to the complex collection of joints and intricate soft tissues that make up the hand (Figure 23.3). Note in Figure 23.3 the ulnar deviation of the fingers and the more functionally debilitating deformity of the volar subluxation of the metacarpal heads that robs the flexor tendons of a proportion of their power, thus weakening grip. The multi-disciplinary team (MDT) within specialist hand units assess, surgically treat and rehabilitate patients to regain hand function. The most common surgical procedure is the replacement of the MCP joint by a silastic flexible hinge (Figure 23.4), developed by Swanson. A flexible implant arthroplasty is different in principle from other joint arthroplasties in that the implant acts as an inert flexible spacer, which is quickly surrounded by a layer of synovial tissue. The new tissue remains in contact with the implant and surrounding this a stronger capsule develops. Postoperatively, the short-term aims are: • to achieve a functional arc of movement; • to protect soft tissue repairs; • to prevent further deformity at the affected joint and the development of secondary deformities/pathological change in the related musculoskeletal system; These aims are achieved by early controlled movement, which stimulates the formation of a strong, but flexible, capsule around the implant. The most common way of controlling the movement is by the use of a dynamic extension splint (DES), often referred to as an ‘outrigger’ (Figure 23.5), although in recent years static splinting regimes have also been developed (Figure 23.6).

Joint arthroplasty

Introduction

Shoulder arthroplasty

Pathology

Surgical technique

Prosthetic design

Rehabilitation programme

The hand

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine