Intertrochanteric Hip Fractures: Arthroplasty

George J. Haidukewych

Benjamin Service

INTRODUCTION

The number of patients treated for intertrochanteric hip fractures continues to increase and represents a significant financial and societal impact. The vast majority of intertrochanteric hip fractures treated with modern internal fixation devices heal. However, certain unfavorable fractures patterns, fractures in patients with severely osteopenic bone, or patients with poor hardware placement can lead to fixation failure with malunion or nonunion. Randomized prospective studies of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly osteoporotic patients treated with internal fixation have shown high complication rates. For this reason, most surgeons favor arthroplasty, which has fewer complications and offers the advantage of early weight bearing. This has led some surgeons to consider the use of a prosthesis in the management of selected, osteoporotic, unstable, intertrochanteric hip fractures. In theory, this may allow earlier mobilization and minimize the chance of internal fixation failure and need for reoperation. The use of arthroplasty in this setting, however, poses its own unique challenges including the need for so-called calcar replacing prostheses, and it raises questions regarding the need for acetabular resurfacing and the management of the often-fractured greater trochanteric fragment. The purpose of this chapter is to review the indications, surgical techniques, and specific technical details needed to achieve a successful outcome. Also addressed are the potential complications of hip arthroplasty for fractures of the intertrochanteric region of the femur.

INDICATIONS

The overwhelming majority of intertrochanteric hip fractures, whether stable or unstable, will heal uneventfully when the procedure is performed correctly, using modern internal fixation devices. Both intramedullary nails and a compression screw and side plate have proven safe and effective. Several European studies have found that hip arthroplasty can lead to successful outcomes; however, there is a higher perioperative mortality rate among these patients compared to those who undergo internal fixation. In North America, the indications for hip arthroplasty for peritrochanteric fractures include patients with neglected intertrochanteric fractures (>6 weeks) when attempts at open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) are unlikely to succeed; pathologic fractures due to neoplasm (primarily metastatic disease); internal fixation failures or established nonunions where the patient’s age or proximal-bone stock precludes revision internal fixation; and in patients with severe preexisting, symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip with an unstable fracture pattern. Recent studies have documented that hip arthroplasty for salvage of failed internal fixation provides predictable pain relief and functional improvement.

PATIENT EVALUATION AND PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Because these patients are typically elderly and frail with multiple medical comorbidities, a thorough medical evaluation is recommended. Preoperative correction of dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and anemia is important. In acute cases, surgery is performed within 48 hours of injury to avoid prolonged recumbency

following medical consultation. When done as a reconstruction procedure, it is scheduled as an elective procedure similar to a total hip.

following medical consultation. When done as a reconstruction procedure, it is scheduled as an elective procedure similar to a total hip.

Plain anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the hip, femur, and pelvis are important for preoperative planning. If the surgeon has any concern regarding the possibility of a pathologic fracture, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning can be helpful. If a pathologic fracture due to metastasis is diagnosed, full-length femur radiographs are critical to rule out distal femoral lesions that would impact treatment. Appropriate imaging of the proximal fragment is important to allow templating of the femoral component for length and offset as well as to determine whether a proximal calcar augmentation will be necessary to restore the anatomic neck-shaft relationship. Careful scrutiny of the hip joint is necessary to determine whether a total hip arthroplasty is needed rather than hemiarthroplasty. A final decision is often made intraoperatively after visual inspection of the quality of the remaining acetabular cartilage. If previous hardware from internal fixation is present, implant-specific extraction equipment and a broken screw removal set, with or without the use of fluoroscopy, are invaluable. Obtaining the original operative report can assist the surgeon in determining the implant manufacturer if it is not recognized from the radiographs. Templating cup size and femoral component length and diameter is an important part of the preoperative plan.

It is often difficult to determine preoperatively whether hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty is appropriate, and whether a cemented or uncemented femoral component fixation is necessary. I prefer to have a variety of acetabular resurfacing and femoral-component fixation options available intraoperatively. Although having such a large inventory of implants available for a single case is cumbersome, it is wise to be prepared for unexpected situations that arise during these challenging reconstructions.

To evaluate infection as a possible contributing factor in a patient with failed internal fixation, a complete blood count with differential, a sedimentation rate, and a C-reactive protein should be obtained preoperatively. I have not found aspiration to be predictable in the setting of fixation failure and rely on preoperative serologies and intraoperative frozen section histology for decision making.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The exact surgical technique will vary, of course, based on whether the reason for performing the arthroplasty is an acute fracture, a neglected fracture, a pathologic fracture, or a nonunion with failed hardware. However, many of the surgical principles are similar regardless of the preoperative diagnosis.

General or regional anesthesia is utilized. The patient is placed in lateral decubitus position using a commercially available positioner on the operating room table. An intravenous antibiotic, typically a first-generation cephalosporin, is given. Antibiotics are continued for 48 hours postoperatively until the intraoperative culture results are available and then stopped or continued if the culture is positive. We carefully pad the down side, insert an axillary roll, protect the peroneal nerve area, and ankle to minimize the chance of neurological or skin pressure problems due to positioning. A stable vertical and horizontal position allows the surgeon to improve pelvic positioning, which facilitates proper acetabular-component implantation when necessary. Several commercially available hip positioners are available that provide accurate and stable pelvic positioning. Consideration should be given to the use of intraoperative blood salvage (cell saver), as these surgeries can be long with significant blood loss.

The leg, hip, pelvis, and lower abdomen are prepped and draped in the usual fashion. If possible, the previous surgical incisions are used. If no previous incision is present, then a simple curvilinear incision centered over the greater trochanter is recommended. The fascia is incised in line with the skin incision, and the status of the greater trochanter is evaluated. If the greater trochanter is not fractured, either an anterolateral or posterolateral approach can be used effectively based on surgeon preference. In the acute fracture situation, it is always preferable, if possible, to leave the abductor-greater trochanter-vastus lateralis complex intact in a long sleeve during the reconstruction.

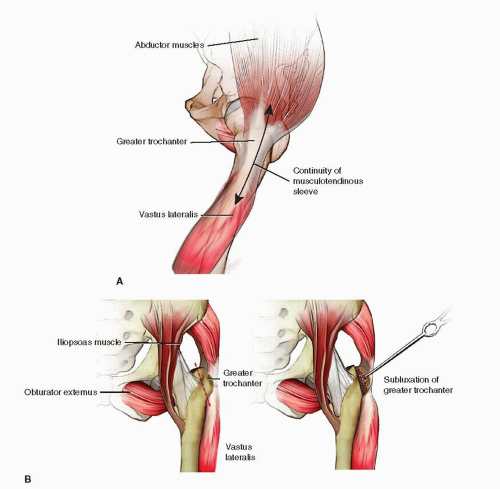

In nonunions or neglected fractures, the trochanter may be malunited and preclude access to the intramedullary canal. In this situation, the so-called trochanteric slide technique may be useful (Fig. 19.1). The technique of preserving the vastus-trochanter-abductor sleeve may minimize the chance of so-called trochanteric escape and should be used whenever possible.

If hardware is present in the proximal femur, I have found it helpful to dislocate the hip prior to hardware removal. The torsional stresses on the femur during surgical dislocation can be substantial, especially in these typically stiff hips, and iatrogenic femur fracture can occur with attempted hip dislocation. Whether removing an intramedullary nail or sliding compression hip screw and side plate, having implant-specific extraction tools is extremely helpful. The principles of reconstruction are similar regardless of whether a nail or plate was used. If previous surgery has been performed, intraoperative cultures and frozen section pathology are obtained from the deep soft tissues and bone. If there is evidence of acute inflammation or other gross clinical evidence of infection, the hardware is removed, all nonviable tissues are débrided, and the proximal femoral-head fragment is resected with placement of an antibiotic-impregnated polymethacrylate spacer. Reconstruction is delayed 6 to 12 weeks or longer while the patient receives organism-specific intravenous antibiotics based on the intraoperative cultures.

With the hip dislocated either anteriorly or posteriorly, the proximal fragment is excised, and the acetabulum is circumferentially exposed. The quality of the remaining acetabular cartilage is evaluated. If the cartilage is well preserved, then a hemiarthroplasty is most commonly utilized. Appropriate attention to head size with hemiarthroplasty is important as an undersized component can lead to medial loading, instability, and pain, while an oversized component can lead to peripheral loading, instability, and pain as well. If preexisting degenerative change is seen on radiographs or the acetabular cartilage is damaged from prior hardware cutout, a total hip replacement is strongly recommended. Of course, even in the setting of normal-appearing acetabular cartilage, an acetabular component may provide more predictable pain relief, and this decision should be made at the time of surgery. The acetabulum is carefully reamed because these hips do not have the thick, sclerotic subchondral bone commonly found in patients with osteoarthritic hips. The acetabulum is reamed circumferentially until a bleeding bed is obtained. I prefer uncemented acetabular fixation due to the versatility it allows with the liner, bearing surface, and head size options. I also typically augment the cup fixation with several screws.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree