15 Key Points 1. Effective pressure ulcer (PU) management requires consideration of multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors. 2. A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach is essential to achieve successful PU management outcomes. Individual members of the multidisciplinary team contribute their own expertise while collaborating and communicating with other team members about risk modification. 3. Many pressure ulcers are preventable with the use of appropriate, currently available interventions. The clinician’s focus is on modification of as many medical risk factors as possible. The nursing process facilitates assessment and evaluation of PU status and assists in determining new strategies. Physical, occupational, and other rehabilitation therapists develop individualized, comprehensive plans for pressure management based on patient and family education together with assessment and selection of support surfaces and positioning devices for effective pressure relief. Nutrition, psychosocial status, and patient education are all critical factors in PU prevention and management. 4. Biomedical engineering enables technological advances in PU prevention and assessment. To successfully prevent pressure ulcer (PU) formation, it is essential to understand the fundamental concept that there are multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors leading to the development of PUs. Having a PU not only greatly impacts a person’s quality of life, it also places a heavy burden on the health care system in treatment costs.1 Recent trends in health care delivery suggest a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach to achieve successful wound management outcomes.2 The team typically includes physicians, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, dietitians, and psychologists, together with some input from biomedical engineers (Fig. 15.1). This chapter addresses the essentials of PU management from the perspectives of a multidisciplinary PU management team. Fig. 15.1 Multidisciplinary wound care model: spinal cord injury patient at risk/with a pressure ulcer. The clinician must address as many medical risk factors as possible while realizing that some may be rather difficult to correct or eliminate. These factors can be arbitrarily divided into intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors. Intrinsic factors refer to the internal medical factors of the individual. These include motor paralysis, muscular atrophy, mobility impairment, sensory impairment, nutritional impairment, anemia, and vascular compromise due to large-vessel disease or microvascular disease. Many medical conditions and lifestyle choices may lead to increased intrinsic PU risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus or any medical condition that results in anemia and impaired nutrition; neuromuscular diseases, such as poliomyelitis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or critical illness polyneuropathy; and any acquired condition, such as spinal cord injury (SCI), stroke, or traumatic brain injury, that leads to impaired mobility and/or sensory loss. Lifestyle choices like smoking3 and alcoholism are also associated with an increased risk of PU development (see the Psychology section). Some intrinsic risk factors may be more easily corrected than others. For instance, smoking may be more reversible than muscular atrophy secondary to a neuromuscular disease. Extrinsic factors are environmental in nature and include the local environment of the skin (e.g., moisture level, which may be affected by sweating and bowel/bladder incontinence), interface pressure and shear force between the skin and the support surface (while seated or in bed), friction,4 and psychosocial support. Many extrinsic factors interact with the intrinsic factors. For instance, mobility impairment may lead to bowel and bladder incontinence, which in turn will affect the local skin microenvironment by creating excessive skin moisture, hence increasing the risk of PU development. Another example is nutritional impairment, which may lead to muscular atrophy, hence negatively impacting on the interface pressure between the weight-bearing skin areas of the body and the supporting surface. Some extrinsic factors are more easily addressed than others. For instance, providing the appropriate support surfaces may reduce the interface pressure fairly easily, but lack of psychosocial support may be much more difficult to address. It is clear that intrinsic and extrinsic PU risk factors are often interdependent and complex, requiring a comprehensive interdisciplinary team approach to successfully prevent PU development. The primary approach involves the identification of significant risk factors by the various team members, each focusing on their own area of expertise while collaborating and communicating with the other team members about risk modification.5 This often necessitates the establishment of a multidisciplinary skin care team. All members are specialists in PU prevention and treatment, with one taking the leadership role. For example, a patient with a history of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, and smoking has been admitted to the inpatient rehabilitation unit following a stroke that has resulted in left hemiplegia, bladder incontinence, and dysphagia. This individual has multiple intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for PU development, and a suitable team management approach is shown in Table 15.1. The specific role of each discipline will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter. The team regularly discusses progress in risk factor modification and monitors skin status closely. This is a highly interactive and collaborative process. The nursing process is an integral part of nursing practice that allows for the assessment and evaluation of PU management and assists in determining new strategies.6 The nursing process for PU management begins with nurses, assessing patients for risk factors that affect nursing care.6 Upon completion of a comprehensive assessment, nurses create client-specific care plans determined by an individual’s risk factors and based on clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). Nurses also plan for the implementation of the individualized care plan, apply nursing interventions accordingly, evaluate current wound care practices and modalities in use, and determine if specific expected outcomes have been met.6 Documentation is a key communication tool that captures the established basis for initial and revised care plan development. Table 15.1 Multidisciplinary Team Management of At-Risk Patient Specialty Role Physician Provide optimal management of underlying clinical conditions, e.g., diabetes and peripheral vascular disease Nurse • Complete nursing pressure ulcer risk assessment score • Ensure appropriate positioning and pressure relief while in bed • Perform appropriate management of bladder incontinence Dietitian Aggressively address nutritional issues arising with diabetes and dysphagia Physical and occupational therapists Address seating and positioning issues Psychologist • Address potential cognitive issues that may impair the patient’s understanding of pressure ulcer prevention • Provide smoking cessation counseling Screening tools like risk assessment scales are designed to help clinicians identify high-risk patients.7 The importance of completing comprehensive patient evaluations cannot be overstated. These include determining available support systems (such as home care resources), the patient’s PU risk factors, and any existing PUs. There are a variety of PU risk assessment tools or scales available. It is important to validate assessment scales as reliable in use within their intended population.8 For example, the Salzberg scale focuses on PU risk assessment factors specifically for persons with SCI. These factors include restricted activity level, degree of immobility, level of injury, urinary incontinence, autonomic dysreflexia, advanced age, the presence of comorbidities, as well as residence and nutrition (hypoalbuminemia or anemia).9 However, there is much controversy regarding whether this specific scale is the best predictor. Studies to determine initial PU development prediction and recurrence using the Salzberg scale are favorable but must be considered preliminary at this time.10 Other PU risk assessment scales include the Norton, Waterlow, Gosnell, Knoll, and Braden.11 The Braden scale is currently most used in the United States and has been found to have the best predictive value in a review of seven risk assessment scales used with individuals with SCI.8 Other multicenter prospective studies have published replicated findings that have strongly suggested the Braden scale to be a valid and reliable tool.11,12 The Braden scale consists of six subscales: sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear,7 each with a numerical range of scores. The friction/shear subscale ranges from 1 to 3; the other subscales range from 1 to 4 (1 = lowest possible score). Lower scores indicate higher risk for PU development.7 Nurses and other health care professionals can use the Braden scale as an outline for risk assessment and care plan development. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), in collaboration with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), encourages prevention as the first line of defense against PUs.13 Prevention is much less costly than treatment, and the AHRQ CPG v3 suggests the need to increase education and quality improvement methods.14 Forward-thinking tactics such as these foster the development of prevention initiatives useful for high-risk areas of care. The AHRQ CPG 3 advises that patients be assessed for risk on admission and periodically as determined by the unit or facility (e.g., daily or weekly).15 The NPAUP CPG further advises the need for reassessment at regular intervals based on changes in patient condition, acuity levels and current care settings.16 There are a variety of CPGs in addition to those from AHRQ and NPUAP, including the National Guideline Clearing-house created by the American Medical Directors Association (AMDA),17 Quality Improvement Organization (QIO) guidelines,18 Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN) best practice guidelines,19 National Institutes for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines,20 and Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines.21 Each guideline contains similar recommendations regarding risk assessment, prevention, PU assessment, measurement, treatment, and documentation; however, they also contain significant differences. The best CPG for an individual facility can thus vary based on overall facility policy. It is important to follow updated published guidelines and best practice methods that focus on prevention and treatment central to good patient care.22 Current practices in PU prevention and management support the nursing process in addition to comprehensive collaborative efforts.23 The patient-specific nursing care plan should be based on education relating to self-care deficits and assistive education relating to PU prevention, moisture assessment, and bowel and bladder management.24 Nurses must determine the patient’s readiness to learn and the patient’s current level of relevant knowledge. Education-based PU prevention protocols targeted at specific risk factors may reduce future PU development.25 Structured education protocols can increase a patient’s knowledge base, correcting misguided beliefs and improving understanding of personal risk.26 Teaching strategies should focus on identifying both internal and external factors, which the patient may have some control over. For at-risk individuals with no current PU, the care plan should include preventative education focused on daily skin inspection and keeping bed linens dry, clean, and wrinkle free.24 Individuals and their families should be involved in the planning and implementation process as well. Patients’ involvement in their own care will increase autonomy and may be beneficial for implementation. Loss of bowel and bladder control is one of many complications consequent to SCI. In the SCI population it is important to focus on the strategies relating to moisture, nutrition, friction, and shear.27,28 Nurses must be aware of the impairments and difficulties bowel and bladder management may present. In addition to medications and dietary recommendations, nurses must create care plans based on guidelines for avoiding high-risk behaviors and conditions that can lead to impaired skin integrity.29 When applying facility CPG recommendations to the Braden subscale relating to moisture, nurses create a care plan based on nursing assessment and diagnosis of individuals with SCI found to be at risk for impaired skin integrity relating to moisture.30 The goal is removal of excess moisture, especially for those who perspire heavily and experience fecal and urinary incontinence, without drying out the client’s skin.7 Protective barriers, such as creams, drying powders, or moisture-absorbing pads, should be applied as appropriate. Nurses should also teach and assist patients to become active participants in the care and maintenance of external or internal urinary devices (external catheters, indwelling catheters, or intermittent catheterization devices) to ensure proper elimination and decrease moisture exposure.31 Regularly scheduled bowel care is also important. Encouraging patients to be active in daily skin inspections and providing information and assistance with methods and devices reinforce effective bowel and bladder management. In addition to minimizing modifiable risks for their patients, nurses help to maximize independence. Planning and implementation of a nursing care plan should be based on measurable goals. Standardized documentation of care plan development, implementation, evaluation, and actual outcomes is important. Documentation is also invaluable for continuous evaluation and improvement of the nursing process and current care. Education and instruction can increase self-care compliance in anticipation of required needs at home.24 When teaching new behaviors or tasks, an immediate demonstration of the activity should be used to assess a patient’s understanding. Nurses must also ensure the behavior is being performed consistently over a determined time frame.26 For example, daily skin inspections should be completed consistently for 5 days, and three to five reasons for adherence to bowel and bladder management plans should be verbalized. Follow-up evaluations can determine if patients are achieving expected outcomes This aspect of nursing care planning enables review of the nursing process and records the appropriate cost-effective services provided as well as information provided to clients and families. Many PUs are preventable with the use of appropriate interventions,32 and appropriate pressure relief must always be provided. Although 2-hour turn schedules are commonly used in nursing practice, the rationale for this time interval is not well established.23 It has been suggested that regular turn schedules combined with low-air-loss support surfaces are required to maximize benefit.32 To make the best decision for PU treatment, the wound must be assessed and its stage or grade determined. Wound characteristics of importance include size, location, and wound bed appearance. The NPUAP has been instrumental in developing a standard approach to wound staging to accurately communicate the degree of tissue damage.33 In 2007, a category of suspected deep tissue injury (DTI) was added to the overall classification.34 Other PUs are categorized in four stages or as unstageable (Table 15.2). Stage II through IV PUs may exhibit a yellow, tan, gray, or brown substance called slough. Tissue surrounding the wound should also be assessed to determine local skin health. It is also important to note that the initial staging of a PU dictates the permanent description of the wound, even when it has healed. For example a stage IV ulcer that is now healed will be a “healed stage IV.” Its stage will never be reversed to a stage I or zero. Currently, wound measurements are obtained by measuring wound edge to wound edge and recording first the length, then the width, and then the depth. Advances in technology are needed (see the Biomedical Engineering section). Irregularly shaped wounds can make measurement more difficult. Wound measurement is always based on the face of a clock, although orientation of the clock face varies with wound location. Specifically, wounds on the feet will use the heel as the 12 o’clock landmark and the toes as the 6 o’clock landmark. Wounds anywhere else on the body use the client’s head as 12 o’clock with the toes at 6 o’clock. Head to toe is always used for length and side to side for width.33 Measurements are typically taken using a cotton tip applicator and a disposable ruler. Wound depth is measured with the applicator in the deepest area of the wound bed, grasping the applicator with the thumb and forefinger and maintaining the finger placement upon withdrawal and ruler measurement. In addition to wound area irregularities, tunnels, epiboly (premature closure of the wound edges), sinus tracts, and areas of undermining may be present as well. It is important to use the clock system to describe the location and direction of PU irregularities, always taking precautions not to lose the applicator in tunneled areas of the wound. Table 15.2 NPAUAP Classification of Pressure Ulcers Pressure ulcer type Characteristics Suspected Deep Tissue Injury Localized area of intact skin with dark discoloration beyond that of an individual’s normal skin color Stage I Detectable nonblanchable areas of intact skin with the appearance of persistent redness in lightly pigmented skin. Patients with darker skin may present with darker tones in skin color, such as a deepened red, blue, or purple hue. Stage II Shallow or superficial wound, such as an abrasion or crater that involves partial-thickness skin loss. Partial-thickness skin loss could involve the epidermis, dermis or both. Stage III Full-thickness skin loss. Presents clinically as a deep crater most often involving damage to subcutaneous fat. May extend down to underlying fascia, although bone, tendon, and muscle are not visible. Stage IV Full-thickness skin loss extending beyond underlying fascia with evidence of tissue destruction, necrosis, and/or the damage of muscle, bone, and supporting structures Unstageable Full-thickness skin loss with wound bed covered in slough or eschar. True depth cannot be determined until the wound is chemically debrided, removed by sharp debridement, or allowed to fall off naturally. Wound bed assessment includes tissue type and characteristics, exudate, and environment.35 Tissue destruction is either partial or full thickness; however, the descriptions of tissue characteristics vary. Tissue color within the wound bed is an important characteristic. In general, reddish pink to red indicates healthy tissue with a good blood flow. Granulation tissue is living viable tissue with a puffy, bubbled, reddish pink appearance. Poor blood flow results in tissues that appear pale pink. In wounds that extend beyond the superficial layers, the epithelial tissue may be pearly pink. In superficial wounds, epithelial tissue may develop in islands. Necrotic (dead) tissues come in a variety of colors: necrotic (dark/black), necrotic slough (yellow/green/gray/tan), or necrotic eschar (dark or black, thick hard crust). Yellow and green usually indicate infection. Overhydrated moist tissues appear white and macerated. Wound exudate colors also communicate vital information. Clear or serous fluids and sanguineous (bloody) drainage are normal in the acute inflammatory phases of wound healing. Increases in the amount of drainage could be troublesome. Colors indicative of necrosis and infection in the wound bed are also indicative of infection if found in drainage (purulence) as well. Temperature, moisture, and the presence of bacteria all influence wound management. Wound healing occurs at normal body temperatures.36 Temperature decreases are related to loss of moisture from the wound. Moisture vapor within tissue is lost with every dressing change, and it can take the body hours to return to adequate body temperature. Even a 2°C decrease can delay wound healing.35 Nutrient-rich moisture within a wound bed indicative of good blood supply is desirable. A dry wound bed slows healing and increases the likelihood of scar formation.37 Nurse education of patients includes the need to prevent the wound from drying out.38 However, copious amounts of odoriferous fluid are undesirable. Wounds should be cleaned prior to assessment to avoid confusion with the odor of a treatment option. Bacteria inhibit wound healing by competing for nutrients and oxygen, Necrosis or bacteria within a wound cause odors that can be described as pungent, foul, strong, fecal, or musty. Bacteria-ridden wounds can also smell sour or sweet. Documentation of wound bed assessments relays vital information to several disciplines and assists in determining a selection among treatment options. Treatments and dressing choices should be based on clinical intention, wound location and type, product availability, and cost. Preventative treatments, such as protective dressings applied directly to the skin, protect against initial skin breakdown. Adhesive dressings provide a protective environmental barrier. Nonadhesive moisture control barriers, such as creams, ointments, gels, pastes, and skin sealants, can also protect against breakdown. Product selection for wound treatment should focus on wound characteristics and appearance and provide improved wound healing. Cleansing of the wound bed is an important component of PU care, thus it is important to select the optimal cleansing solution prior to dressing placement.39 Although common in home use, tap water cleansing is not clinically recommended due to variable quality. Normal saline is currently most used in practice and is a cost-effective isotonic solution that will not cause tissue damage. Commercial cleansers are usually recommended to facilitate removal of wound bed debris, which could lead to infection. These solutions should be used carefully; they may harm healthy tissue if they are not applied as directed. It is important to pat surrounding skin dry after irrigation and before the application of a clean dressing to prevent maceration or damage of viable tissue due to cleansing or debriding solutions. Selection of an appropriate debriding agent is also important. Debriding products include solutions, ointments, and creams containing enzymes that digest necrotic nonviable tissue and promote epithelialization. Wound dressings range from gauze to hydrocolloids, impregnated matrixes to foams, and more. Dressings for open wounds with depth can absorb drainage, add moisture, reduce bacteria, combat infection, and control odor. One should choose a dressing that facilitates a moist environment conducive of wound healing (Table 15.3). Physical, occupational, and other rehabilitation therapists in the SCI interdisciplinary team play a critical role in PU prevention and management. Therapists develop individualized, comprehensive plans for pressure management based on patient and family education, together with assessment and selection of support surfaces and positioning devices. There are two main goals in PU education; the first is to have patients and caregivers understand who is at risk, the barriers to remaining ulcer free, their specific risk factors, and how modifications in habits, actions, and environment can prevent skin breakdown. The second is that prevention will begin as a therapist-directed activity but will gradually shift to an entirely patient-initiated practice in all areas of life and at all times. Gibson suggested that, though patients were knowledgeable about PUs and motivated to look after their health, they tended to rely too heavily on the SCI unit rather than be independent with their care.40 King et al. found that, although patients may believe they are at risk and that prevention is important, they do not follow through with corresponding preventative actions.41 Effective education must be initiated early, provided on an individualized basis, and approached in a hands-on manner.42 It has been shown that individualized education and structured monthly follow-up can effectively reduce the frequency, or delay recurrence, of PUs.43 Education should be an ongoing process provided to anyone at risk, including patients with acute injuries and individuals aging with an SCI, even though they may have successfully avoided a PU thus far. There are many barriers to remaining PU free. The most preventable barrier is that patients are unaware of their risk. SCI often occurs due to a traumatic accident with multiple complications; prevention of something that may happen is low on the priority list, and therefore education never occurs. If patients are made aware of their elevated risk, they are frequently not told the consequences of having a PU, nor where or what to look for. Without the sensation of pain, a PU can quickly form and go unnoticed until a host of secondary complications have arisen. Therefore, it is imperative to the health and well-being of the patient that education begins early in the rehabilitation process and continues throughout the life span. Patients need to be made aware of the risk factors that lead to increased incidence of PUs.44 Schubart et al. analyzed the educational needs of adults with SCI and found that awareness of lifelong risk for PU development, including the ability to self-assess risk factors and how risk changes over time, was one of the most important needs of this population.44 Nonmodifiable risk factors include required medications, genetics, body type, comorbidities like diabetes, level of injury, and the individual’s cognition. Age is another risk factor due to decreased flexibility, lack of functional mobility, and reduced financial resources as well as increased body mass and escalating caregiver burden. Modifiable risk factors include nutrition, body weight, skin care, and pressure management. Individuals who maintain a normal weight, return to meaningful roles in life, and do not have a history of tobacco use, suicidal behaviors, self-reported incarcerations, alcohol abuse, or drug abuse are less like to develop a PU.45 Rehabilitation therapists tend to focus on modifiable risk factors to teach individualized prevention strategies for different activities. Skin care education is important for individuals with SCI and encompasses several components.44 Patients must control skin contact with moisture, including a bowel and bladder continence program and managing sweat. One of the most frequently taught preventive behaviors is daily visual and tactile skin checks. This can be facilitated through a flexible mirror that can be held at various angles in order for the patient to check all common PU locations. Alternative techniques or inspection by a caregiver may be necessary for individuals with restricted mobility. Individuals should learn the most frequently affected body locations, what skin changes to be aware of, and the importance of reporting any skin changes to their doctor in a timely manner.46 Pressure management is a modifiable risk factor that therapists should address through a 24-hour plan of care for all at-risk patients. This includes selection of appropriate pressure relief technique(s), wheelchair, wheelchair cushion, mattress, and positioning while in bed. The goal of effective pressure management is to ensure skin integrity while maximizing independence with activities of daily living. It is important to realize that those with new injuries are unlikely to realize they are at any risk of PUs due to lack of protective sensation and the ironic fact that the primary behavior associated with PU development is inactivity rather than behavior.9 Until the individual acquires the necessary insight and skills, performance of a pressure management regimen will initially be the responsibility of members of the interdisciplinary team. As the individual achieves an understanding of the risks and consequences of PUs and becomes able to perform these techniques, responsibility for pressure management is shifted to the individual. To establish a regimen of pressure management that will be effective for a given individual, the rehabilitation therapist must identify which pressure relief techniques are most effective, provide the individual with various forms of feedback to demonstrate their effectiveness, and reinforce the need to perform these techniques with the appropriate frequency and duration. Although the term pressure relief is frequently used to describe weight shifts, in reality these techniques are used to shift pressure from one location to another or redistribute it across a greater surface area. Numerous studies have been performed on the effectiveness of weight shifts in preventing PU development; however, there is currently no consensus on which technique is most effective. Similarly, there has been no definitive research to indicate the optimum frequency and duration of performing pressure relief. This lack of consensus is due to differences in methodology and measurement variables. Some studies have been based on the measurement of interface pressures with the support surface, whereas others have looked at tissue oxygen perfusion.47–49 There is, however, universal consensus that weight shifts are essential to preventing PUs. The CPGs currently recommend that therapists help the individual establish a specific pressure relief regimen within the individual’s capability and that this regimen be performed every 15 to 30 minutes.46 For individuals with sufficient upper extremity function and sitting balance, the full push-up, side or lateral lean, and forward lean are the three most commonly used techniques. While the wheelchair push-up can eliminate pressure over the ischial tuberosities, studies of tissue oxygen perfusion suggest that tissue must be unloaded for well over 60 seconds to return to baseline levels. This may be impractical for many individuals with SCI and over time may subject the joints of the upper extremities to excessive stress. For these reasons, techniques that involve leaning may increasingly be gaining favor. For individuals who lack the physical ability to effectively perform weight shifts, prescription of a mechanical tilt or recline system is recommended. Coggrave and Rose found that at least 65 degrees of tilt was required to recover oxygen perfusion in unloaded tissue.47 Other studies have found a combination of a 45 degree tilt and a 120 degree recline provided the greatest reduction of interface seating pressure.50 These authors and others have found that, although individuals frequently accessed their power tilt function, very few tilted further than 45 degrees.50,51 Interface pressure mapping can be an effective tool for providing feedback regarding the pressure-reducing properties of a wheelchair cushion, specialty mattresses, and other support surfaces. To utilize this technology therapeutically, however, it is important to understand system capabilities. Most clinically available pressure mapping systems include sensors that measure vertical pressure only and cannot detect shear forces, friction, or the effects of any contour provided by the seating system. Unless routinely recalibrated, the sensitivity of sensor mats will change over time. Thus, caution should be exercised when one is comparing current versus historical results. This is especially true in the absence of frequent recalibration. Pressure mapping can be used to assess the effectiveness of different types of cushions, identify uneven pressure distribution due to asymmetry, and optimize overall pressure distribution of a seating system through changes in its configuration. Perhaps its most effective use, however, is its ability to demonstrate the effectiveness of weight shifts and other pressure management strategies. Rehabilitation therapists play a primary role in support surface selection. When assessing pressure-reducing properties of support surfaces, such as wheelchair cushions and specialty mattresses, therapists must consider both the pressure being exerted by the support surface and the forces exerted by the support surface due to shear, friction, moisture, and other factors. No single clinical tool or standard can definitively determine which support surface will be best for an individual. Therefore, therapists must rely on a combination of their clinical judgment and objective findings, such as pressure mapping, to select appropriate support surfaces. When choosing a mattress, it is important to consider comfort, individual risk factors, and the caregiver’s capabilities. Mattresses are divided into static (low-tech) and dynamic (high-tech) categories. Static mattresses and overlays consist of foam, static air, water, or gel. Dynamic mattresses use alternating pressure, low-air loss, or air-fluidized surfaces to provide therapeutic pressure management. A systematic review of support surfaces concluded that, when compared with standard hospital mattresses, both static and dynamic surfaces can reduce PU incidence.52 These authors also found that research on the relative efficacy of static and dynamic surfaces is currently inconclusive. Current clinical recommendations are that at-risk individuals should use a static mattress and those with a history of PU should utilize a dynamic surface. Cushion selection is a key part of pressure management for an individual following SCI. Clinicians must be knowledgeable about the properties of the various types of cushions to select the best cushion for each individual. Cushions usually use the properties of air, fluid, various densities of foam, or a combination. Air- and fluid-based cushions use the principle of providing immersion of bony prominences to maximize the amount of surface area, thus decreasing pressure. Foam cushions provide less immersion but provide better stability, which can reduce shear or redistribute pressure away from bony prominences onto areas that can tolerate additional pressure. Rehabilitation therapists who specialize in providing seating/wheeled mobility also incorporate pressure management and reduction of shear into every aspect of an individual’s wheelchair and seating system. Scoliosis, pelvic obliquities, and other postural deformities are frequently complications of SCI, and the resulting asymmetry can result in uneven pressure distribution over bony prominences. Lateral trunk support utilizing contoured backs and other devices can help prevent deformity progression and redistribute pressure away from the affected area. Following selection of an appropriate support surface, positioning must be considered. CPGs recommend that cushions and positioning aids should be used to decrease pressure on high-risk areas or areas with current PUs. It has been shown that optimal side-lying is achieved when cushions are used to position the patient at a 30 degree angle to bed surface, with 30 degrees of hip flexion and 35 degrees of knee flexion, making sure the lower leg is below the midpoint of the body.53,54 Common practice is to turn the patient every 2 hours (see the nursing discussion above), but there is insufficient evidence to establish a protocol in this area. It is also recommended that the head of the bed be kept at or below 45 degrees unless medical complications preclude this.55 The duration of head elevation should also be minimized. Head elevation leads to increased sacral region pressure and shearing forces as gravity pulls the patient down the length of the bed. Therapists train and educate patients on all aspects of transfers, such as when transferring from bed to wheelchair. To ensure skin protection during transfers, it is important to educate patients on avoiding excessive shearing forces and friction. Therapists train patients on performance of appropriate transfer techniques for their functional level during the acute rehabilitation. Transfers can be broken down into four categories: independent self-transfer in short or long sitting; self-technique with adaptive equipment, such as a transfer board, caregiver-assisted technique with or without adaptive equipment; or the totally dependent transfer with adaptive equipment, such as a lift device. Regardless of the transfer utilized, therapists must educate the patient and caregiver on the proper technique to reduce risk of skin breakdown. Patients are trained to ensure adequate buttock clearance to prevent excessive shearing forces. Inadequate buttock clearance during lateral transfers causes excessive shearing and repetitive skin microtrauma. Assessment of transfers does not end following acute rehabilitation, and periodic assessments of transfer technique may be required. For example, as patients age, they may experience a decline in their level of function and lose the ability to properly transfer independently. Retraining on transfers with assistance may be required to reduce the risk of skin breakdown. Therapists provide patient and caregiver education and training on the importance of maintaining adequate lower-extremity range of motion for positioning in a wheel-chair and lying in bed. This is extremely important to prevent limb contractures, which can cause excessive pressure points on bony prominences. Most patients with fully preserved upper-extremity strength can be instructed on performing self– range-of-motion (ROM) exercises independently. When patients are unable to perform self–ROM independently, they are educated on how to instruct caregivers on providing proper lower-extremity ROM exercises.56 Rehabilitation therapists are involved with PU adjunctive care utilizing therapeutic modalities or biophysical agents. Biophysical agents include hydrotherapy, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, radio frequency, electromagnetism, phototherapy, and negative pressure. Current research has not substantially demonstrated a superior adjunctive therapy modality or biophysical agent utilized in PU management, and more research is needed.57–59 Following a surgical flap procedure for wound closure, patients are usually placed on bed rest for approximately 6 weeks, usually determined by the individual surgeon. During this time, therapists provide essential education of the patient, caregivers, and fellow medical staff members on proper bed positioning to ensure pressure relief for optimal healing of the post-surgical site. Therapists provide bedside upper extremity strengthening to improve strength in preparation for transfer training. At 6 weeks, therapists initiate lower-extremity ROM exercise, including achieving 90 degree hip flexion, in preparation for wheelchair sitting. Following remobilization, therapists will evaluate transfers, wheelchair positioning, and cushioning to ensure optimal pressure relief is maintained. Prior to discharge, overall sitting time is usually increased gradually over 2 to 3 weeks up to a total of 5 hours of sitting daily.46 Nutrition is integral to the effective medical management of individuals with SCI. In the acute phase, individuals are hypermetabolic, and nutritional needs are increased. Chronically, energy expenditure is less than that for able-bodied individuals. Individuals with SCI are at increased risk for obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease.60 The Metropolitan Life Insurance tables have been used as a guide to determine the target body weight for SCI individuals; however, they require adjustment to correct for loss of body mass due to paralysis. Neither body mass index (BMI) nor skin-fold measurement should be used to measure body composition in individuals with SCI.60 There are two methods for adjusting the tables.60,61 1. Paraplegia (a) 5 to 10% lower than table weight or (b) 10 to 15 lb lower than table weight 2. Quadriplegia, (a) 10 to 15% lower than table weight or (b) 15 to 20 lb lower than table weight Energy expenditure is decreased in individuals with SCI, more so with quadriplegia than with paraplegia, due to denervated muscle.62 As a measure of nutrition in SCI, 24-hour urine urea nitrogen has been shown to be unreliable.46 Indirect calorimetry is the preferred method for determining energy needs in critically ill patients.60 The Harris-Benedict equation is used to estimate the daily calorie requirements using basal metabolic rate (BMR). Specifically; In people with SCI, the Harris-Benedict equation may be used acutely based on admission weight with an injury factor of 1.2 and a stress factor of 1.1, if indirect calorimetry is not available.60 During rehabilitation, energy needs may be determined using 22.7 kcal/kg for individuals with quadriplegia and 27.9 kcal/kg for individuals with paraplegia.60,62 Daily protein needs during acute SCI should be calculated using 2.0 g protein/kg actual body weight. During rehabilitation, protein needs should be calculated using 0.8 g to 1.0 g protein/kg of body weight for maintenance of adequate protein stores in patients without PUs or infection.60 A registered dietitian should assess all individuals with SCI for risk factors associated with PU development. Nutritional assessment includes evaluation of biochemical parameters together with other factors, such as daily food/fluid intake, changes in weight status, diagnosis, lifestyle, and medications. The maintenance of nutrition-related parameters is associated with a reduced risk of PU development.60 Nutritional assessment for PU healing includes all factors assessed for PU prevention. When a PU is present, visceral protein may be lost. Historically, serum albumin levels have been used as an indicator of visceral protein status. However, albumin has a half-life of 12 to 21 days and may be influenced by nonnutritional factors, such as infection, acute stress, surgery, and hydration status. Although prealbumin may also be influenced by stress and inflammation, it has been proven to be a more useful indicator in assessing the effectiveness of nutritional intervention due to its shorter half-life of 2 to 3 days.63,64 Prealbumin is a negative acute phase reactant and will transiently decrease in the presence of inflammation and stress (e.g., immediately postsurgery).64 Concurrent assessment of C-reactive protein can differentiate whether prealbumin is being affected by stress and inflammation. Prealbumin levels may also be maintained during states of malnutrition.1,60 Energy/calories promote anabolism, synthesis of collagen and nitrogen, and healing. Energy needs for individuals with SCI and PUs may be estimated using predictive equations if indirect calorimetry is not available, using either 30 to 40 kcal/kg body weight daily or the Harris-Benedict value times stress factor (1.2 for stage II PU, 1.5 for stage III and IV PU).60 Protein is essential for collagen synthesis. Protein losses occur through wound exudates, leading to deficiencies that delay wound healing.65 Daily protein loss has been shown to increase from 2 to 1.5 g/kg body weight with a stage II PU to 1.5 to 2.0 g/kg for stage III and IV PUs.60,65 High protein levels (> 2 g/kg) have been found to contribute to dehydration in the elderly.65 Thus protein needs should be individualized because higher protein intakes may be contraindicated in individuals with concomitant renal or hepatic impairment. Current recommendations for fluids are based on guidelines for the non-SCI population. The normal daily fluid requirement is 30 to 40 mL/kg. Additional fluids (10 to 15 mL/kg) may be required when using air fluidized beds set at temperatures more than 31 to 34°C (88 to 93°F).60 Adequate vitamin and mineral intake is best achieved through the consumption of a balanced diet. Optimal micronutrient intakes to promote PU healing are not currently known due to insufficient research. Deficiencies of specific nutrients have been associated with impaired or delayed wound healing. Supplements should be offered when deficiencies are confirmed or suspected or when dietary intake is poor.65 Individuals with SCI and a PU should consider taking a daily multivitamin and mineral supplement.60 Caution should be used with administration of individual supplements of micronutrients. Intakes of vitamins and minerals should not exceed 100% RDA. Only when a true deficiency exists should a single micronutrient supplement be provided. Appropriateness of supplement administration should be reviewed by a registered dietitian every 7 to 10 days.60 Ascorbic acid is essential for collagen synthesis. Deficiency of ascorbic acid has been associated with delayed tissue repair and impaired immune function. Ascorbic acid supplements have been shown to promote wound healing only in patients with an ascorbic acid deficiency. Individuals at risk for ascorbic acid deficiency include the elderly, smokers, those who abuse drugs, and those who are medically stressed.65 Current recommendations for daily vitamin C supplementation in individuals with deficiency are 100 to 200 mg for those with stage I and II PU and 1000 to 2000 mg for those with stage III and IV PU.60,65 Individuals with renal failure are at increased risk of developing oxalate stones, and ascorbic acid supplementation should not exceed 60 to 100 mg daily.65 Zinc is necessary for cell replication and growth and is important for protein and collagen synthesis. Zinc deficiencies are common in individuals with diarrhea, malabsorption, or hypermetabolic stress.65 If zinc supplementation is indicated, it should be administered in divided doses at no more than 40 mg of elemental zinc per day for no more than 2 to 3 weeks.1,65 Zinc supplementation offers no benefit for those who are not deficient. High serum zinc levels may inhibit healing by impairing phagocytosis and interfering with copper metabolism.1,60,65 Supplementation with zinc is contraindicated in individuals with stomach or duodenal ulcers. Zinc toxicity symptoms include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and headache.66 To promote optimal stool consistency, a daily minimum of 1.5 L fluid is required for individuals with SCI and neurogenic bowel.60 Fluid needs are estimated as either 1 mL/kcal estimated energy needs plus 500 mL, or 40 mL per kg body weight plus 500 mL.60 Fiber intake should be initiated at 15 g/d then gradually increased to no more than 30 g/d.60 Fiber intakes more than 20 g/d may result in undesirable prolonged intestinal transit time.60 Interface pressure (IP) mapping is the most widely used technique for objective evaluation of individuals at risk for PU development. As discussed elsewhere in this chapter, direct applied pressure at the skin surface is by no means the only cause of ischemia leading to tissue breakdown. Interface pressure measurement should always be considered as one of several components in overall patient evaluation when assessing PU risk status. With that caveat, interface pressure mapping can provide much critically valuable information. To provide accurate information about loading conditions at the interface between a patient and the support surface, be it a cushion or a mattress, the sensor used should not disrupt the interface conditions by its presence. Thus sensors must be thin, flexible, and accurate. For clinical use, assessment systems should also be reliable, be easy to set up and calibrate, and have clear output data. Over the past decade, technological advances in sensor design and image processing software have greatly improved both the accuracy and the usability of commercially available interface pressure mapping systems. This has led to the potential for increased clinical use in seating evaluations. For example, one leading company, Tekscan Inc. (South Boston, MA), has seen sales of clinical pressure mapping systems more than double for the past 5 years, compared with a decade ago. The primary uses of interface pressure mapping are to provide information on the postural effects of seating system configuration and on the pressure distributive effects of various cushion options. However, interface pressure mapping also has the potential to be an important educational and monitoring tool for both patients and clinicians. Real-time pressure maps provide biofeedback so that the patient can immediately see the effects of weight shifting and other pressure relief maneuvers. For example, it has been found that, although paraplegics are generally taught to relieve pressure intermittently using lifts, the majority cannot perform a lift that totally relieves pressure under the ischial regions. However, individuals with some trunk control are able to effectively decrease regional interface pressures by leaning either side to side or forward.47 They can also maintain this posture for a sustained period, which allows regional blood flow to increase gradually, relieving localized ischemia. Advances in IP sensors and hardware have been accompanied by research into analytical approaches. Currently commercially available systems include software that provides the clinician with average and peak pressures, either for the total contact area or for user-selected regions of interest (ROI), such as the ischial or sacral areas. Selection of ROI is very user intensive and cannot reliably quantify significant changes between assessments. It has been suggested that health care professionals use pressure maps qualitatively rather than quantitatively (i.e., by visual impression rather than mean or maximum pressures). Human visual perception is more sensitive to spatial changes that occur with movement rather than changes in color alone.67 When considering interface pressure maps, this corresponds to peaks of high pressure as opposed to regions of evenly distributed pressure. Thus, subjective rankings of pressure maps obtained from very different surfaces may agree well with peak pressures but not mean pressures.68 Just as advanced image processing techniques are increasing the amount of information obtained from techniques like computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), so sophisticated data analysis methods provide an opportunity to get more out of the massive amounts of data obtained from interface pressure mapping assessments. For the most part, these developments arise from research studies where the goal is to examine similarities between study participants For example, Brienza et al. employed a data reduction approach known as singular value decomposition (SVD) to compare pressure and shape contour maps for seated subjects.69 Eitzen70 used a frequency analysis method to determine how often all observed pressure values occurred over an extended assessment period. This approach makes greater use of available data obtained over an extended assessment. Comparison of output distribution graphs can also visually represent differences between assessments. However, Eitzen felt it was too technically challenging to show real-time changes in frequency distribution during an assessment. Our group has developed an automated analytic tool that determines changes between all regions of the contact area without any requirement for user selection of ROI. The Longitudinal Analysis with Self-Registration (LASR) statistical algorithm was therefore developed to compare multiple datasets obtained over time or under different conditions. Because the whole contact area is analyzed, significant differences across the entire spatial contact area can be determined for both static and dynamic assessments. This can include repeated short-term assessments, such as assessing several different seating cushions for a patient or evaluating the effect of changing the configuration of a patient’s wheelchair (e.g., tilt-in-space or with footrest adjustment). Individuals with SCI are also often seen repeatedly over several years, and many factors related to PU risk will change over time. It is important to be able to make valid comparisons between pressure maps obtained over long time intervals. It is also most efficient in clinical settings for pressure maps to be analyzed in a real-time, or near-real-time, manner to aid clinical interpretation and decision making. Pressure mapping produces large-volume datasets, which generally require extended processing times, thus limiting the ability to provide real-time analysis. LASR employs efficient data-mining techniques to allow rapid maximum information recovery from the large volume of data obtained for each subject assessed. In our current research, LASR has been used to show that gluteal electrical stimulation is effective in changing seating interface pressures in a manner that may indicate improved tissue health.71 The LASR tool is available at our Web site (stat.case.edu/lasr). Blood carries nutrients, including oxygen, to the tissues. Blood flow is thus essential for maintenance of tissue viability (i.e., prevention of PUs). Several noninvasive techniques are available, including transcutaneous blood gas measurement, laser Doppler flowmetry, and photoplethysmography. Animal studies have also used contrast-enhanced MRI to monitor changes indicative of deep tissue injury.72 In vascular disease management, peripheral blood flow measurement has a long history of use in determining the level of lower limb amputation.73,74 In the field of PU management, blood flow monitoring has largely been limited to research applications.75–78 However, Coggrave and Rose showed that transcutaneous blood oxygen measurement can readily be incorporated into clinical seating evaluations and can provide valuable insights for improving PU prevention practice.47 Changes in wound size are a major component of monitoring wound healing. Accurate wound measurement is challenging in clinical practice. Almost all PUs are irregular in shape and often have indistinct margins, and it may be difficult to position the patient reproducibly for repeated measurements. Standard clinical techniques often use manual linear measurement of maximum wound length, width, and depth (see the nursing discussion above). Digital imaging is becoming increasingly common in clinical practice as new technology becomes available.79 Our group performed a pilot study to compare the reliability of the standard clinical measurement tool, linear measurement, with two electronic devices, specifically the Visitrak automated digitizing table (Smith and Nephew, Largo, FL), and the VeVMD digital image analysis software (Vistamedical, Winnipeg, MB, CA).80 Forty two-dimensional (2-D) “wound” templates of varying sizes were created and mounted on a contrasting background to maximize ease of margin delineation. Wound size was measured using all three techniques by clinical personnel blinded to the actual wound size and experienced in wound evaluation. It was found that intraobserver variability was not significant for any technique. However, interobserver variation was significant (p < 0.01) for linear measures at all wound sizes and for electronic measures with larger wounds only. These findings indicate that the standard clinical technique of linear wound measurement is neither reliable nor accurate, even when employed by experienced clinicians. The Visitrak and VeVMD systems showed improved measurement accuracy with some dependence on the size of the wound. Wound depth was not considered in our pilot study, but it is recognized to be a significant factor in successful wound healing. Further research is still needed to determine accurate methods for wound depth measurement. One promising approach is the use of stereophotogrammetry to construct three-dimensional (3-D) images from stereotactic 2-D images. Two images of an object viewed from slightly different angles can be combined to give an image with a perception of depth. The technique was first applied to wound measurement over 20 years ago.81 Although patient assessment was quick and noninvasive, image processing was slow at that time and required extensive observer training. Advances in digital technology and image analysis have recently led to the development of more clinically useful systems. The LifeViz™ 3-D system (Quantificare Inc., Santa Clara, CA) is a cost-effective stereophotogrammetry system that was initially developed, tested, and validated by a team of imaging experts at the University of Glamorgan, Wales. The LifeViz™ system uses the same principles as the human visual system to achieve depth perception. A specialized lens combined with conventional digital camera equipment obtains two views of the wound from slightly different angles. Images can be readily analyzed to determine several variables, including wound area, length, width, circumference, and volume. Both digital images and quantified outcome measures can be included in the patient’s record. It should be noted that, although 3-D imaging provides more accurate information than linear measurement, caution is still required when assessing PUs that exhibit significant undermining or tunneling. There is evidence that substance abuse, cigarette smoking, and depression are risk factors for PU development for individuals with SCI. Since the 1970s, research has examined several psychosocial variables that may either increase vulnerability to PU development or serve as buffers against them. The role of psychology on the interdisciplinary wound care team involves identifying and treating contributory mental health conditions and fostering adaptive behavior. Psychosocial factors should be considered in all cases when assessing for patients’ risk for developing a PU or when treating wounds that have already occurred. Many of these psychosocial factors can be modified to improve outcomes and need to be considered as part of an interdisciplinary care plan. Possible protective influences include knowledge of and adherence to behavioral prevention strategies (see Rehabilitation Therapists), strong social support, problem-solving skills, and employment. Although the research evidence for psychosocial variables is sometimes mixed, understanding behavioral mechanisms in PU development remains important for individualized treatment SCI clinicians place a great deal of weight on psychosocial variables in PU prevention and management. A survey of SCI specialty physicians and nurses found that 97% agreed with the following statement: “In the vast majority of cases, when patients are compliant with prevention measures, pressure ulcers can be avoided.” Ninety-one percent also agreed that “patient lack of responsibility is an important risk factor for developing pressure ulcers,” and over 75% endorsed that a history of mental health problems and active substance abuse represent important issues to consider in hospital admission and discharge decisions.82 The clinicians in the survey considered that, regardless of injury level, individuals with strong social support were less likely to be admitted for a PU and required less wound healing for discharge. The SCI population has a higher base rate of alcohol and substance use than the general population.83,84 Some studies suggest a link between alcohol/drug abuse and PU development.45,85 By definition, substance abuse involves impairment in an individual’s ability to perform daily functions.86 There-fore, it is reasonable to be concerned that substance abuse among individuals with SCI may interfere with their consistent performance of PU preventative behaviors.83 Postinjury use of illicit drugs and misuse of prescription drugs increase the likelihood of PUs. The effects of alcohol use/abuse are less clear, with several studies failing to find a significant association.3,87,88 Heinemann and Hawkins suggest that a history of preinjury problem drinking or substance abuse may point to an impairment in coping skills and predispose people to PUs even in the absence of current use.89 Nicotine constricts blood vessels and decreases blood flow, especially to the extremities.90 Decreased blood flow increases the risk of tissue breakdown and can hinder the healing process of an existing wound. Accordingly, cigarette smoking has been targeted as a behavioral risk factor for PU management. The evidence for the relationship between smoking and PU risk is clear-cut. Smith et al. showed that smoking significantly increased the odds of PU development.88 Other studies have suggested that a history of past smoking, such as the lifetime number of cigarettes smoked, also relates to PU incidence.3,45 The implementation of smoking cessation interventions among SCI patients represents a critical area for risk reduction Although most individuals who sustain an SCI do not become depressed, having an SCI does increase the risk of depression. Up to 30% of individuals with an SCI will experience a depressive disorder.91 Depression may interfere with an individual’s energy level, motivation, and ability to concentrate and problem solve, thereby affecting the ability to engage in PU prevention tasks. Investigations of the link between PUs and depressive symptoms have shown mixed results. Some studies have supported the association between PU development and depressive symptoms,3,45,88 whereas others demonstrate no correlation.89,92 Although the relationship remains inconclusive, the high incidence of depression in SCI requires careful assessment for depressive symptoms in all patients, so that those who need it have access to treatment. Several demographic and lifestyle factors have been identified as protective against PUs. Variables with empirical support include having a college education, being married, being employed, living an overall healthy lifestyle (specifically exercise and healthy diet were found to be protective), having an internal locus of control, and possessing good problem solving skills.3,45,85,93 It is interesting to note that individuals with SCI who are employed have a lower incidence of PUs. One might speculate that employment would increase sitting time and distract from preventative behaviors, potentially increasing the odds of developing a PU. In contrast, research clearly shows that employment is a protective factor that correlates with positive health outcomes. Educating patients with SCI regarding PU prevention should be central to the initial rehabilitation process (see Rehabilitation Therapists). Knowledge of and adherence to these strategies are widely believed to be strong buffers against developing PUs. The evidence that following self-care recommendations reduces PU incidence is currently inconclusive.3,45,94,95 These findings should not detract from the importance of patient education but rather indicate the multifaceted nature of PU prevention. Most individuals with SCI possess both psychosocial vulnerabilities and buffers to PU development.85 PU development is likely when risk factors outweigh protective factors, and the relationship among variables may be complex. For example, a previous history of PUs may be considered a risk factor for one person, but for another it may produce increased vigilance and act as a buffer.85 Psychologists on SCI treatment teams can assist in PU prevention and management by identifying psychosocial risk and protective factors and providing intervention accordingly. Depression can be successfully treated among individuals who have an SCI with the use of antidepressant medication or psychotherapy or both.96 Smoking cessation and substance abuse treatment can also be addressed. It can be difficult for individuals with SCI to attend substance abuse group treatment sessions while hospitalized, especially if they are on bed rest. However, patients on bed rest are also unable to engage in tobacco or substance use. This period of abstinence provides an opportunity to help patients examine their use and potentially enhance motivation for behavioral change. Motivational interviewing is an effective counseling approach for these types of behavioral changes.97,98 Nicotine replacement therapy can also aid patients willing to pursue smoking cessation. Although there are several behavioral interventions that can help individuals stop smoking, there is evidence that many individuals interested in smoking cessation are never offered such treatment.99 It is recommended that patients’ readiness to stop smoking be assessed and interventions be tailored accordingly.99 Prior to PU treatment it is important to have a discussion with the patient about the expectations of a wound care plan, such as bed rest and smoking cessation. If patients are aware of and agree to a treatment plan ahead of time, the likelihood that they will be adherent to treatment expectations may increase. Pearls

Interdisciplinary Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Medical Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Medical Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Medical Approaches to Pressure Ulcer Prevention

Medical Approaches to Pressure Ulcer Prevention

Nursing Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Nursing Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Risk Assessment Scales

Risk Assessment Scales

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Nursing Care Planning

Nursing Care Planning

Bowel and Bladder Management

Documentation and Home-Care Management

Current Nursing Practices in Pressure Ulcer Treatment

Current Nursing Practices in Pressure Ulcer Treatment

Pressure Ulcer Assessment Pressure Ulcer Staging

Pressure Ulcer Assessment Pressure Ulcer Staging

Pressure Ulcer Measurement

Wound Bed Assessment in Pressure Ulcers

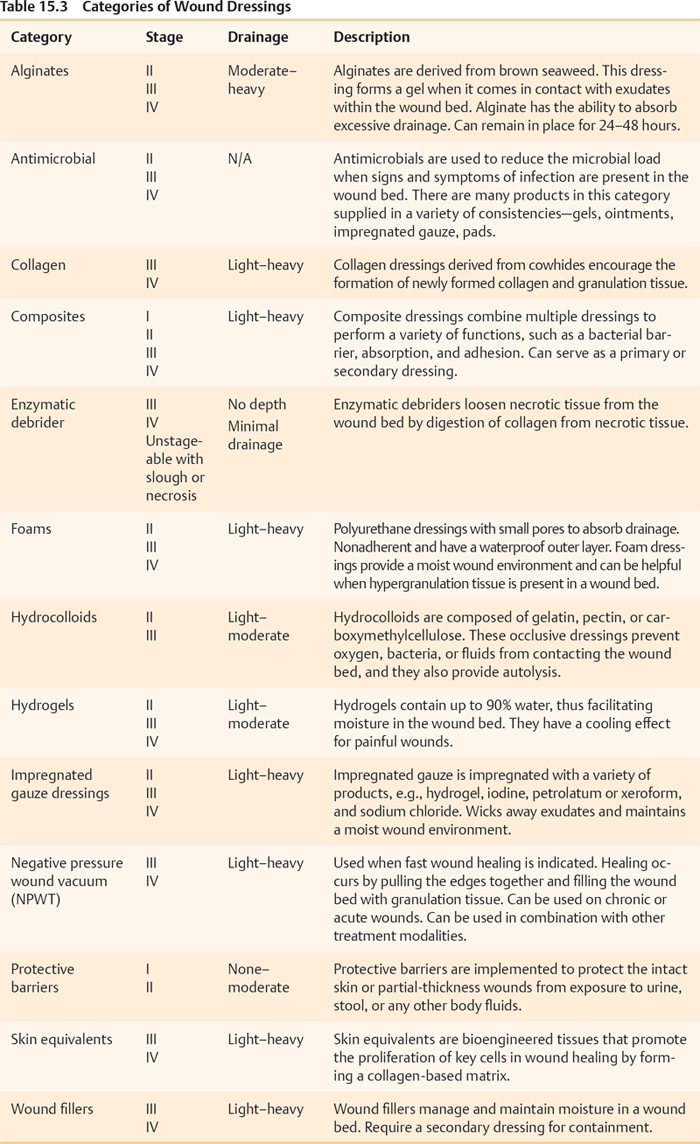

Selection of Pressure Ulcer Dressings: Treatment Options

Rehabilitation Therapist Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Rehabilitation Therapist Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Pressure Ulcer Education

Skin Inspection

Pressure Management for Pressure Ulcer Prevention

Establishment of an Individualized Pressure Management Program

Techniques to Shift Weight and Redistribute Pressure

Pressure Mapping

Support Surface Selection

Specialty Mattress Selection

Wheelchair Seating Selection

Positioning

Transfers

Spasticity

Adjuvant Treatment Modalities

Postsurgical Flap Procedure for Wound Closure Management

Nutritional Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Nutritional Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Male: BMR = 66 + (13.7 × weight in kg) + (5 × height in cm) − (6.76 × age in years)

Male: BMR = 66 + (13.7 × weight in kg) + (5 × height in cm) − (6.76 × age in years)

Female: BMR = 655 + (9.6 × weight in kg) + (1.8 × height in cm) − (4.7 × age in years)

Female: BMR = 655 + (9.6 × weight in kg) + (1.8 × height in cm) − (4.7 × age in years)

Essential Nutrients for Pressure Ulcer Prevention

Nutritional Assessment for Pressure Ulcer Healing

Essential Nutrients for Wound Healing

Fluid Needs for Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury and Pressure Ulcers

Vitamins and Minerals

Nutritional Needs and Neurogenic Bowel

Biomedical Engineering Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management: Biomedical Approaches to Risk Assessment

Biomedical Engineering Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management: Biomedical Approaches to Risk Assessment

Technical Developments in Pressure Mapping: Accuracy of Measurement and Improved Data Analysis

Blood Flow Measurement: Tissue Oxygen and Blood Flow

Biomedical Technology Advances in Pressure Ulcer Measurement

Psychological Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Psychological Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management

Physiological Vulnerabilities to Pressure Ulcers

Substance Abuse

Cigarette Smoking

Depression

Physiological Buffers from Pressure Ulcers

Patient Education/Preventative Behaviors

Intervention

Pressure ulcer management must address the whole patient, not just the wound(s).

Pressure ulcer management must address the whole patient, not just the wound(s).

Pressure ulcer management by an interdisciplinary team is integral to successful outcomes.

Pressure ulcer management by an interdisciplinary team is integral to successful outcomes.

Nutritional and psychological evaluation must be included in pressure ulcer management.

Nutritional and psychological evaluation must be included in pressure ulcer management.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Interdisciplinary Essentials in Pressure Ulcer Management