CHAPTER 34 Instability treatment failure—common reasons and prevention

Failure of the treatment of anteroinferior instability of the shoulder (i.e., recurrence of instability) can be considered to result from two principal causes: (1) poor understanding and recognition of the patient factors and structural lesions that predispose towards the recurrence of instability and (2) failure to perform the appropriate procedure for each individual patient with an instability problem.

Failure of the treatment of anteroinferior instability of the shoulder (i.e., recurrence of instability) can be considered to result from two principal causes: (1) poor understanding and recognition of the patient factors and structural lesions that predispose towards the recurrence of instability and (2) failure to perform the appropriate procedure for each individual patient with an instability problem. Selection is the key to preventing recurrence following anterior instability surgery. It comprises careful preoperative patient selection, accurate preoperative and intraoperative assessment of soft tissue and bony lesions, and choosing a treatment modality that can reliably solve the specific instability problem encountered.

Selection is the key to preventing recurrence following anterior instability surgery. It comprises careful preoperative patient selection, accurate preoperative and intraoperative assessment of soft tissue and bony lesions, and choosing a treatment modality that can reliably solve the specific instability problem encountered. In a retrospective analysis of treatment failures following arthroscopic Bankart repair, glenoid and humeral bone loss, as well as anterior and inferior hyperlaxity, were found to significantly predispose towards recurrent instability. Patient age (<20 years), type of sport (contact or forced overhead sports) and level of practice (competition) are additional factors that have been implicated in the etiology of recurrent instability.

In a retrospective analysis of treatment failures following arthroscopic Bankart repair, glenoid and humeral bone loss, as well as anterior and inferior hyperlaxity, were found to significantly predispose towards recurrent instability. Patient age (<20 years), type of sport (contact or forced overhead sports) and level of practice (competition) are additional factors that have been implicated in the etiology of recurrent instability. Using clinical history, examination, and plain radiographs alone, the Instability Severity Index Score (ISIS) can be calculated and used to assist in the determination of the appropriate surgical procedure that will result in the lowest probability of recurrence following surgery for anteroinferior instability.

Using clinical history, examination, and plain radiographs alone, the Instability Severity Index Score (ISIS) can be calculated and used to assist in the determination of the appropriate surgical procedure that will result in the lowest probability of recurrence following surgery for anteroinferior instability. For those patients in whom an isolated Bankart repair is insufficient, the additional procedure should depend on the predominant type of anatomic lesion encountered: capsular deficiency and/or bony deficiency. The surgical intervention is tailored towards the underlying structural problem: (1) Trillat procedure (transfer of the coracoid process over the subscapularis) for patients with a deficient anterior capsule but no bone loss, (2) Bristow-Latarjet procedure (transfer of the coracoid process through the subscapularis muscle onto the anterior glenoid surface) for patients with glenoid bone deficiency, and (3) Hill-Sachs remplissage (transfer of the posterosuperior capsule and infraspinatus in the humeral defect) for patients with isolated humeral bone loss.

For those patients in whom an isolated Bankart repair is insufficient, the additional procedure should depend on the predominant type of anatomic lesion encountered: capsular deficiency and/or bony deficiency. The surgical intervention is tailored towards the underlying structural problem: (1) Trillat procedure (transfer of the coracoid process over the subscapularis) for patients with a deficient anterior capsule but no bone loss, (2) Bristow-Latarjet procedure (transfer of the coracoid process through the subscapularis muscle onto the anterior glenoid surface) for patients with glenoid bone deficiency, and (3) Hill-Sachs remplissage (transfer of the posterosuperior capsule and infraspinatus in the humeral defect) for patients with isolated humeral bone loss.Introduction

Recurrence of instability represents the leading complication of arthroscopic shoulder stabilization.1 Recurrence following anteroinferior instability surgery can be clearly defined as a further dislocation or any subjective complaint of subluxation. In our opinion, it is appropriate to also include a “persistent apprehension” that causes functional limitation or pain in the throwing position, as an additional factor that can be considered as a treatment failure. In our experience, a patient who is practicing any sport that needs abduction-external rotation of the arm (throwing movement), with or without contact, will not be able to return to the same level of practice if he or she still presents with anterior apprehension of the shoulder.

In the nineties, arthroscopic Bankart repair became the standard of care for recurrent anterior shoulder instability in many surgical centers. However, in the last years, it has become clearer that this unique surgical procedure could not, by itself, stabilize all shoulders with recurrent anterior instability. Because revision surgery results in a poorer outcome for the patient than a primary procedure,2 it is appropriate that the principal focus of attention be directed towards the prevention of failure. By identifying patient factors that predispose to failure and performing a precise preoperative and intraoperative assessment of potential structural lesions, the correct surgical treatment may be tailored to the patient. The current evidence regarding common reasons for failure following instability surgery must be explored under the headings of preoperative history, examination, and radiographic findings, such that “at risk patients for arthroscopic Bankart” may be identified in a systematic manner. Although difficult to quantify, additional factors such as surgical technique and surgeon experience have an undeniable impact on the probability of failure following instability surgery.

Determination of risk factors associated with instability recurrence following arthroscopic bankart repair

Preoperative history

Patient age

Although no clear age limit has been defined, younger patients are at greater risk of recurrence following surgery for instability. The age of onset of instability is predictive of the redislocation rate. Patients experiencing single dislocations have a mean age of 43 years compared with 23 years in recurrent cases.3 Greater soft tissue laxity, higher activity levels, and possibly less compliance with postoperative regimens are cited as the principal explanations for the increased risk of surgical failure in the younger age group.4 Patients over 40 years of age with recurrent anterior instability must be suspected of having associated rotator cuff tears.

Hyperlaxity/capsular deficiency

Poor quality soft tissues caused by multiple previous operations, multiple dislocations, or connective tissue disorders may jeopardize the outcome following instability surgery. Capsular distention have been shown to be irreversible5 and directly related to the number of dislocations or subluxations. In our experience, the number of subluxations is clearly underestimated by patients who mainly recall the true dislocations but seem to forget the episodes of subluxation.

Bilateral symptoms6 should alert the surgeon to the possibility of a hyperlaxity diathesis. Patients with connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome or Ehler-Danlos disease, have joint hyperlaxity and hypermobility.7 In such cases, relatively minor trauma may be sufficient to trigger instability episodes.

Previous shoulder stabilization surgery

Failed arthroscopic thermal capsulorrhaphy may result in severe attenuation and/or loss of capsular structures.8 Patients with previous open Bankart or Bristow-Latarjet may have a deficient subscapularis muscle-tendon unit, which in itself represents a surgical challenge. Although we have excluded such cases from discussion in this chapter, surgeons should realize that they may be a source of instability treatment failure. When contemplating revision surgery, these potential problems may be identified in advance and anticipated by obtaining the operations notes from prior interventions.

Examination findings

Signs of shoulder hyperlaxity

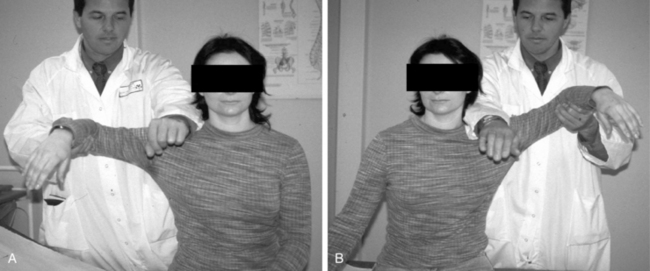

The finding of “shoulder hyperlaxity” must be considered as a factor in the evaluation of recurrent anterior instability. Shoulder hyperlaxity can be anterior, inferior, posterior, or combined (so-called multidirectional instability). Anterior hyperlaxity of the shoulder is present if the examiner can easily subluxate the humeral head out of the socket in the anteroposterior direction on drawer testing or if there is greater than 85 degrees of passive external rotation with the patient’s arm by his or her side9 (Fig. 34-1). Inferior hyperlaxity is assessed with sulcus sign testing and the hyperabduction test,10 which we consider to be positive when there is a minimum of 20 degrees of asymmetric abduction at the glenohumeral joint11 (Fig. 34-2). Finally, a gynecoid morphologic aspect of the patient, as well as skin striae, can be subtle but useful findings suggestive of a predisposition towards soft tissue laxity.

Radiographic findings

Glenoid bone loss

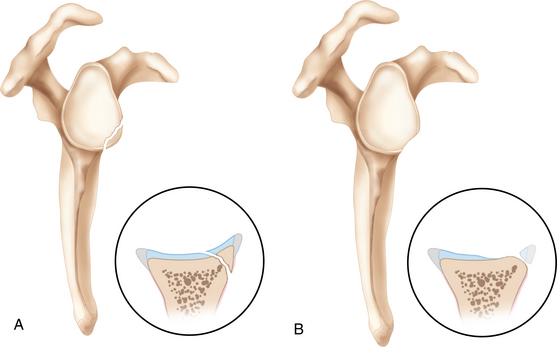

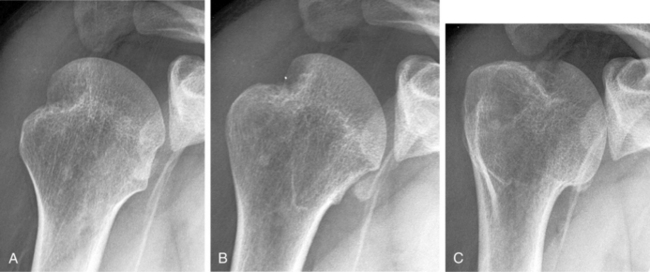

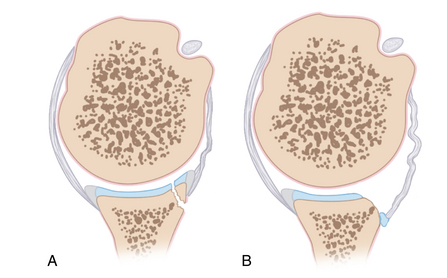

It is important to distinguish between those patients with loss of contour of the glenoid rim and those with glenoid bony avulsion fractures12 (Fig. 34-3). Patients with loss of glenoid contour without any identifiable bony fragment will often have significant attenuation of the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament and the anterior capsular structures (Fig. 34-4). The deficiency in these structures allows recurrent subluxations or dislocations that effectively erode and compress the anterior glenoid. By contrast, in a study of factors influencing recurrence following arthroscopic Bankart repair, avulsion fractures did not represent an identifiable risk factor.13 A possible explanation is that in the setting of avulsion fractures, failure occurs acutely through the bony surface of the glenoid with relative preservation of the attached soft tissues (Fig. 34-5). Although in many instances a bony avulsion fragment will be resorbed over time (Fig. 34-6), if present, it is frequently possible to incorporate the bone fragment into the Bankart repair at the time of surgery.

FIGURE 34-5 A, Glenoid avulsion fracture. B, Loss of bony substance (often associated with a deficient capsule).

Large osseous defects of the glenoid will result in instability regardless of the quality of the capsulolabral repair by altering the glenohumeral contact area and the function of the static glenohumeral restraints.14 Although, several authors reported different preoperative or intraoperative approaches to qualify the orientation or quantify the area of the glenoid bone loss and their thresholds to maintain glenohumeral joint stability, there is consensus on the critical role played by an intact glenoid articular arc in maintaining shoulder stability and function.15

Garth’s apical oblique and the Bernageau profile are specific radiographic views that may assist in the assessment of glenoid bone deficiency, although the most accurate indicator is the en face view of the glenoid visualized on sagittal computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Humeral bone loss

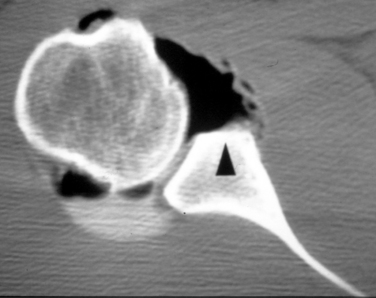

Larger posterosuperior humeral head impression fractures (Hill-Sachs lesions) may precipitate recurrent postoperative instability despite adequate soft tissue capsulolabral reconstruction.16 Combined abduction and external rotation of the arm may bring the Hill-Sachs lesion in contact with the anterior rim of the glenoid. These so-called “engaging Hill-Sachs lesions” run parallel to the face of the glenoid in the abducted externally rotated position of apprehension allowing the humeral head to sublux or dislocate anteriorly (Fig. 34-7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree