6 INJURY PREVENTION

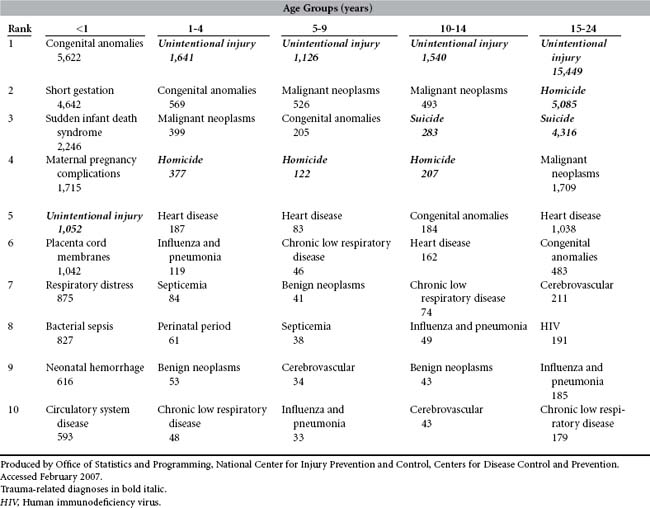

Injury is the most underrecognized public health problem facing the nation today. Overall, injuries (unintentional injuries, homicides, and suicides combined) account for 7% of all deaths in the United States each year1,2 and were responsible for 167,184 deaths in 2004.1 Between ages 1 and 45 years, unintentional injury alone (without the contribution of homicide and suicide) is the leading cause of death2,3 and the fifth leading cause of death across all ages in the United States (Table 6-1).4 Among adolescents and young adults (ages 15 to 24 years), three of every four deaths in 2003 were injury related.1,5 Injury (unintentional injury, homicide, and suicide combined) is the leading cause of premature death for young people and thus is the leading cause of years of potential life lost before the age of 75 years.6 The societal cost of injury is enormous. Health care charges for the treatment of injury represent only a portion of the total financial burden. Other costs include those associated with loss of income, productivity, and property. Social costs are harder to measure but include pain, suffering, reduced quality of life, lost human potential, and disrupted families. For the year 2000 alone, the estimated total lifetime cost resulting from injury in the United States was estimated at $406 billion.7

Injury is perceived to be a condition that affects young people disproportionately, yet trauma continues to be a major health problem throughout life. Despite the obvious importance of injury as a cause of premature death, the highest injury-related death rates are experienced by the elderly—a sector of the population that is expected to increase from 12.4% (in 2000) to 20.4% by the year 2040.8 Similarly, our oldest citizens (those older than 75 years) experience death rates nearly three times those of the general population; this group is expected to increase from 5% to 9% of the population in the next three decades.8 Nonfatal injuries in the elderly are also a major concern. For many older adults, a hip fracture may begin a downward spiral of immobility-related morbidity, an end to independent living in the community, and shortened life span. Indeed, half of all elders who are hospitalized for a hip fracture are unable to return home or live independently after the injury.9 Unless we are able to reduce death and injury rates among people older than 65 years, it is estimated that by the year 2030 this group will sustain more than one third of all injury-related deaths and hospitalizations. The social impact of this cannot be overstated.

Injury can be prevented or controlled at three levels. Primary prevention involves preventing the event, such as the car crash, that has the potential to cause injury. Secondary prevention involves preventing an injury or minimizing its severity during that crash. Tertiary prevention is optimization of outcome through medical treatment and rehabilitation. Trauma nurses will be most familiar with tertiary prevention and to a lesser extent with secondary prevention. Development of emergency medical services and systems and expert trauma management has improved—and will continue to improve—the outcomes of injured patients. However, these advances will never be enough to reduce the toll of injury-related death significantly. Why? The majority of deaths from traumatic injury occur early. It is estimated that, because of the severity of the injuries, half of all trauma deaths cannot be prevented with even the best medical management.10 For those who survive their injuries, the sequelae may be profound and, in some cases, increase that individual’s chance of reinjury.10 Achieving a significant reduction in trauma-related mortality and morbidity therefore must include attention to primary prevention. Indeed, the American Trauma Society website carries the message that when prevention succeeds, trauma is conquered.11

At some time, all trauma nurses will ask, “Could this have been prevented?” Why then has injury prevention received so little attention in trauma training programs and trauma services? Trauma, it seems, is so endemic in our society that we fail to realize the enormity of its financial and social costs or our potential as a society to reduce its toll. In 1988, Dr. William Foege, former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, called injury “the principal public health problem in America today.”12 One year later, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop testified that “if some infectious disease came along that affected children [in the proportion that injuries do], there would be a huge public outcry and we would be told to spare no expense to find a cure and to be quick about it.”13 Much progress has been achieved in the ensuing years, but the commitment of the public, and of the health care profession, to injury prevention is still woefully inadequate—a symptom of society’s “general tendency to underinvest in programs designed to prevent social problems.”14 Why? Three answers come to mind: (1) injury is underrecognized and, as such, grossly underfunded and understudied relative to other health problems of similar magnitude; (2) injury prevention is relatively young as a field of scientific inquiry and professional practice; and (3) training in injury prevention methods is lacking.

Trauma nurses know all too well how a few seconds can alter the course of a healthy young person’s life forever. They have witnessed the effects of alcohol and other substance abuse and access to lethal weapons as risk factors for injury; they recognize predictable trauma case histories; they know that certain days, times, and weather conditions are associated with increased caseload. Fortunately, many have also witnessed the protective effects of interventions such as seatbelts, helmets, and improved vehicle design. Clearly, trauma nurses possess the awareness and many of the attributes needed by injury preventionists and can make valuable contributions to injury prevention. The goal of this chapter, therefore, is to enable the trauma nurse to think about injury in a critical and systematic way. Traumatic injury is approached as a health problem to be solved. A public health problem-solving paradigm15 and two related conceptual frameworks for problem diagnosis and decision making are introduced.

AN OVERVIEW OF INJURY PREVENTION

Although traumatic injury has been a problem throughout the ages, injury prevention is a relatively new field of scientific inquiry. Historically, injuries (often called accidents) have been viewed as the result of human error, fate, or bad luck. Injury prevention efforts reflected and inadvertently supported this belief by encouraging people to adopt safe and responsible behaviors or by blaming the victims for the events that led to their injuries or deaths. Most attempts at injury prevention focused on training individuals to be more careful, a preoccupation with what Leon Robertson called “[a] basic cultural theme… that sufficient education will resolve almost any problem.”16 The concept that injury, like disease, is the product of the interaction of a human host and an agent within the environment, and can therefore be examined by epidemiologic methods, first appeared in the public health literature in 1949,17 more than a century after epidemiologists knew that explaining the development of epidemics as the consequence of individual behaviors was inaccurate and ineffective for the development of preventive strategies. This and later developments in injury control are discussed in a comprehensive article by Julian Waller.18 Dr. Waller, a pioneer of the injury field, is one of many who advocated for the removal of the term “accident” from discussions of injury.19 This was promoted to draw attention to the fact that injuries do not exhibit the randomness conveyed by the term “accident,” and that injuries can be explained by using scientific methods common to public health.20

The late Dr. William Haddon, considered by many to be the father of injury epidemiology, refined the understanding of the role of energy as the agent of injury. Haddon’s work formed the well-known definition of injury published by the National Committee for Injury Prevention and Control in 1989: “Injury is any unintentional or intentional damage to the body resulting from acute exposure to thermal, mechanical, electrical, or chemical energy or from the absence of such essentials as heat or oxygen.”21 A more recent definition from the World Health Organization adds ionizing radiation to the exposure list and includes the important clarification that energy “interacts with the body in amounts or at rates that exceed the threshold of human tolerance.”22

For an energy transfer (or energy deprivation) to occur, a human host and the agent of injury must interact within an environment. Interaction of host, agent, and environmental factors produces both the injury and the eventual outcome from that injury. This pivotal work of identifying the agent of injury and the vehicle (or carrier of the energy) and refining the relationships of host, agent, and environment in producing injury and its outcomes resulted in the development of the Haddon Phase-Factor Matrix.23 This tool is still an important and frequently used conceptual framework in injury epidemiology; it is explained in detail later. Despite these contributions, and later efforts to reject “accident proneness” as an explanation for childhood injuries,24 the tendency to look at human behavior as the root of the injury problem and to focus prevention efforts on changing those behaviors is still pervasive. Individual knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors are very important factors in injury prevention, as is the role of education and health behavior change; but to develop effective, sustainable injury prevention strategies, we must expand our field of vision beyond the individual. In short, we must subject injury problems to thorough scrutiny before we act.

IDENTIFYING AND DEFINING THE INJURY PROBLEM

An important way of classifying injury is by intent: unintentional or intentional. Unintentional injury, sometimes referred to in lay terms as “accidental” injury, includes motor vehicle and other transportation injury, drowning, fire and burn injury, falls, sport and recreational injury, and other unintentional injuries, such as a needlestick injury. Intentional injuries are the result of intended actions. This does not necessarily mean that the result was intended. For example, one person may strike another intentionally without intending to kill that person. Of course, there are many intentional injuries for which the outcome as well as the action was intended. Intentional injuries may be inflicted on another, or they may be self-inflicted, such as completed suicide, attempted suicide, and other self-destructive behaviors, such as self-mutilation. This latter category, assaults and homicides, receives much public attention. Although this is entirely appropriate and necessary, because firearm injuries have become the leading cause of death in some groups and areas of the nation, many health care providers may be surprised to realize that in the United States firearm suicides outnumber firearm homicides (16,750 and 11,624, respectively, in 2004)25 or that, overall, intentional injuries are far less common than unintentional injuries.2,4,5

One of the problems with identifying and defining deaths by intent is that it may break out, and therefore diminish, the apparent magnitude of deaths from the same mechanism. Reporting injuries and deaths by using a matrix approach that places primary emphasis on the cause (or mechanism) of injury and only secondary emphasis on intent is a recent development in the injury field, one with great value for injury prevention policy development.2 For example, in 2004 firearms accounted for 67% of homicides and 52% of suicides but fewer than 1% of unintentional injury deaths.1 The social burden of firearms is most apparent when the primary focus is on the proportion of all injury deaths that are the result of firearm injury. In 2004, firearms accounted for 17.7% of all injury deaths, second only to motor vehicles at 27%.1

The role of alcohol is an example of a problem that is magnified as one looks beyond individual mechanisms of injury. In 2001 there were 75,766 alcohol-attributable deaths in the United States.25 Of these deaths, 40,005 (or 53%) could be considered injury related. The relationship between alcohol consumption and motor vehicle crashes is well described in the scientific literature and kept in the public eye by the tireless efforts of the country’s most successful grassroots advocacy organization, MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving).26 Less well known by the public is the association between alcohol consumption and numerous other types of injury such as boating and drowning deaths, violence, domestic violence, and recreational injury.27,28 Trauma has been called a “symptom of alcoholism,”29 an opinion supported by numerous investigators.27,30,31 Alcohol intoxication on initial admission is also associated with a 2.5-fold increase in the likelihood that the patient will be readmitted for trauma in the future.30 Although alcohol involvement in trauma has decreased by approximately 25% in the past decade, conservative estimates still implicate alcohol and illicit drugs in 19% of the estimated 2.2 million trauma patients hospitalized each year.28 A study of seriously injured patients in a trauma center found that a high percentage of patients were at risk for a current psychoactive substance use disorder and that this group’s prevalence of current alcohol dependence was nearly three times higher than estimates for U.S. residents aged 15 to 54 years.31 Detecting and managing alcohol-related problems in trauma patients poses an enormous challenge to the trauma care system.

• Group (age range, gender, community-dwelling, patients with existing disabilities such as visual impairment, frequent fallers)

• Region (the country, the state, a community, a residential facility)

• Environments (individual homes, nursing homes, recreational facilities, the street, the workplace, unfamiliar environments)

• Circumstances (ice, rain, on stairs, when getting up at night, in the shower, when taking certain medications, during dementia transitions)

• Severity (any fall, any injury, any fracture, hip fracture, traumatic brain injury)

• Consequences (injury requiring hospitalization, disabling injury, injury that requires that the person be placed in an elder care facility, falls that cause elders to restrict their activities from fear of subsequent falls)

• Other social considerations (falls in the uninsured, falls in patients of a certain health maintenance organization, falls in persons with a history of falls, falls that result in litigation)

Careful definition of the problem is the foundation for all future analyses. It may help to ask this question: “What is the specific problem I need to solve—and why?” If the answer is not clear, an intervention cannot be focused adequately. Definitions of injury problems may also evolve over time as our knowledge, awareness, and social practices change. The area of child passenger safety is one such example. At one time the problem definition for deaths and injuries to child motor vehicle occupants might have been that child passengers were unrestrained in cars. An early study by another pioneer of the injury prevention field, Professor Susan Baker, defined a specific problem: disproportionately high injury and death rates in infant passengers. Her work laid the foundation for the development of rear-facing infant seats.32 Next came the realization that children needed special restraints, but the public’s awareness of this fact was low. Attention was given, appropriately, to building public awareness, passing child restraint laws, and making child safety seats available. As safety seat usage rates increased, so did awareness of a new problem: restraint misuse. It was not enough that people knew they should restrain the child in a safety seat, that they purchased a seat, or that they used it all the time. New problems were defined: car seat–vehicle incompatibility, high levels of incorrect use, the problem of rear-facing infant seats placed in front of an air bag. Most recently, there is growing realization that our almost exclusive attention to the youngest children (0 to 4 years of age) and our nonspecific “Buckle Up” message for older children has left the 4- to 8-year-olds inadequately protected in vehicles.33 National attention is now focused on increasing booster seat use in children in the 40- to 80-pound weight range (4- to 8-year-olds), who cannot be restrained adequately by adult seat belts.34

Evolving problem definitions require similar evolvement of injury prevention initiatives. For example, on July 1, 2002, 24 years after the first statewide child passenger safety law was passed in Tennessee, Washington State’s Anton Skeen Law (HB 2675) took effect.35 This bill, signed into law during the 2000 legislative session, was the first state law in the United States to require booster seat use. By November 2006, 38 states and the District of Columbia had enacted some form of booster seat law.36 Members of first responder, trauma, and emergency medical communities played active advocacy roles to help ensure passage of the Anton Skeen Law and are still, as noted by former U.S. Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta on February 14, 2006, “doing their part to address the consequences of this country’s failure to put children in booster seats.”37 There remains much work to be done to increase compliance with the laws, revise other child passenger safety laws and prevention initiatives of yesterday, and limit exemptions and close gaps to keep pace with the changing understanding of what is required to best protect this age group of children in motor vehicles. The critical lesson here is that problem definitions are not universally relevant. Time invested in this problem definition stage of the problem-solving process will reduce subsequent frustration and enhance the potential for success.

MEASURING THE INJURY PROBLEM

What is the magnitude of this injury?

What is the severity of the injury?

How preventable is the injury?

What are the costs of this injury?

Is some group disproportionately affected (e.g., young, urban African-American men; elderly women; children in custody; health care workers)?

What is the public’s interest in this injury problem (e.g., will the public support stronger child passenger safety laws; are they aware that firearms are used more frequently in suicides than in homicides; do they care whether a child’s playground is safe and well maintained)?

What are the consequences of not acting to prevent this problem (e.g., with a rapidly aging population, can we afford to ignore the problem of injuries in the elderly)?

Answering these questions adequately often involves significant training and effort. A complete discussion of measurement methods is beyond the scope of this chapter. Nevertheless, much time, money, effort, and expertise is devoted to measuring the burden of injury, and there are many valuable data resources available to those interested in determining the magnitude of an injury problem. A list of such resources is included at the end of this chapter.

IDENTIFYING KEY DETERMINANTS

Typically, numerous factors interact to produce an injury and its outcome. In focusing prevention efforts on the most obvious factor, usually human behavior, we ignore other critical factors that may in fact be more modifiable than human behavior. The history of efforts to prevent child pedestrian injury is one such example. The road environment is complex; navigating it safely requires significant cognitive ability not present in children before age 9 years.40,41 Although this has been understood for nearly 40 years, when a 5-year-old child is killed or injured as a pedestrian, it is not uncommon to read the phrase “pedestrian error” on the police report. Even when an unsupervised child runs into a road at 10 PM, the incident is frequently called “accidental.” Over the years, most pedestrian safety programs have focused on persuading or training children to be safer pedestrians and have shown little success. But, why should an exclusively child-focused approach work? If we pause to look beyond the victim, we will see numerous other factors that contribute to these injuries: design of the road, traffic speed, traffic density, signage, visibility, the size and design of the vehicle, driver training, driver awareness and behavior (including substance use), supervision of children, the presence of distractions (e.g., dogs, balls, other children), the child’s level of exposure to the traffic environment, the level of traffic enforcement, and the legal and social consequences of hitting a child pedestrian. Individually, each of these factors may influence the child’s risk of injury. Together, their interaction produces a set of circumstances that either supports or discourages the likelihood of pedestrian injury. Examining the presence and interactions of these factors in a systematic way is an important problem-solving step.

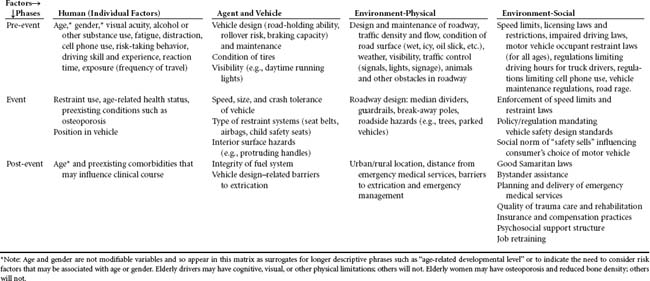

Factors that are important precursors of a public health problem, and therefore possible targets for prevention initiatives, may be referred to as key determinants.15 Key determinants may be numerous. It is important therefore to use an organizational framework to examine these multiple factors and their interactions in a logical manner. Usually organization of key determinants begins by grouping factors. The organizational framework used most commonly in injury problem solving is the Haddon Phase-Factor Matrix. As shown in Table 6-2, the Haddon Matrix is a 3 × 4 table. The four factors of the matrix are human (individual) factors, agent (and carrier) factors, physical environmental factors, and social environmental factors.42 Identifying these factors and assessing their relative importance is crucial to the development of effective prevention strategies. A second important concept is that, although the energy transfer occurs quickly, it is only one part of a dynamic process. Haddon described three phases representing stages in a time continuum that begins before the injury occurs and ends with the outcome. These phases are known as the pre-event, the event, and the postevent phase.42 The interaction of factors in the pre-event phase determines whether an event (such as a car crash) that has the potential to cause injury will occur. Factors interacting in the event phase influence whether an injury will result from this event and what the type and severity of that injury will be. Finally, the interactions in the postevent phase determine the consequences (short- and long-term outcomes) of the injury.

The Haddon Matrix can be used in several ways. Most commonly, it is used to think about the factors involved in an injury problem. Becoming familiar with the literature on the injury problem of interest, before filling out the matrix, will help identify possible risk factors that may otherwise be ignored. Not only does the Haddon Matrix help us to think out of the box (the blame the victim box), but it also helps us identify what we need to find out about the problem. For example, do we have reliable data on restraint use? Do we know how many of the children who do not wear bicycle helmets already own a helmet? The value of the Haddon Matrix is that it illustrates the multifactorial etiology of injury. A potential problem it creates, however, is that one may feel lost in a maze of causal factors. Faced with so much information, some preventionists complain that it is difficult to know what to target. To overcome this problem, it is necessary to take another step. Look at all the factors listed in the matrix and ask which of these factors is controllable? For example, we cannot change an elderly woman’s age but we may be able to enhance her general health status, her muscle tone, or her balance. Next, look at the list of modifiable factors and consider which of these changes is the most likely to be accomplished. For example, which is the most likely to be accomplished: teaching 16-year-old drivers to drive safely or limiting their crash exposure through graduated licensing programs? Look at this final list to determine whether altering the variable would change the outcome significantly. For example, emergency medical services (EMS) response time is modifiable, but some injury mechanisms, such as firearm injury and drowning, result in such severe injuries that enhanced EMS alone does not have the potential to reduce the death toll significantly. This process forms the basis of causal thinking, which is critical to intervention and evaluation planning and is discussed in the next section.

IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

Once the problem is diagnosed and the factor(s) to be targeted with intervention(s) identified (the change targets), the mechanism that will be used to achieve the desired change must be identified. The danger at this point is a “knee-jerk” response when selecting an intervention. The easiest, most obvious, most affordable, or most acceptable strategy is seldom the most effective. As is the case when treatment modalities for injured patients are selected, knowledge of the range of potential injury prevention strategies is critical when prevention options are chosen. Another legacy of Dr. William Haddon is his list of ten injury control strategies that can be applied to all types of injury.42–44 These strategies address the control of hazards with the potential to cause injury, but each targets a different point along a continuum between creation of the hazard and the final outcome. These strategies, with examples of their application, are presented in Table 6-3.

TABLE 6-3 The Haddon Strategies Applied

| Haddon Strategy | Example Applications | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevent creation of the hazard | |

| 2 | Reduce amount of the hazard | |

| 3 | Prevent release of the hazard | |

| 4 | Alter release of the hazard | |

| 5 | Separate person and hazard in time and space | |

| 6 | Place barrier between the person and the hazard | |

| 7 | Modify basic qualities of the hazard | Use breakaway poles near roadways, energy-absorbing surfacing, shatterproof glass in windshields |

| 8 | Strengthen resistance to the hazard | |

| 9 | Begin to counter damage done | Provide early detection: smoke detectors, roadside phones, early warning systems, emergency response systems |

| 10 | Stabilize, repair damage, and rehabilitate |

Adapted from Baker SP, O’Neill B, Ginsburg MJ et al: The injury fact book, 2nd edition, New York, 1992, Oxford University Press, and Haddon W Jr: The basic strategies for preventing damage from hazards of all kinds, Hazard Prev 16:8-12, 1980.

In general, we aim to intervene as early in the causal chain as possible. An analogy used in the injury prevention community is finding multiple people drowning in a river. Do we focus our efforts downstream on pulling them out of the water one by one and attempting resuscitation, or do we walk upstream to find out why they are all falling (or being pushed) into the river? In the acute-care setting, the trauma nurse is the rescuer downstream. Nurses who embrace (directly or indirectly) a primary prevention role move upstream to deal with the factors that led to the trauma epidemic. Fortunately for injury prevention, some trauma professionals have found it possible to do both. Indeed, for accreditation purposes, some trauma services are required to demonstrate involvement in prevention.45 Comprehensive prevention requires work at all levels of the continuum. Investing all our efforts and resources downstream will never be enough to control the injury epidemic. Furthermore, if we fail to monitor activities and trends upstream, we cannot equip ourselves to deal with future consequences downstream.

Perhaps the greatest challenge to identifying effective primary prevention strategies is preoccupation with the individual: the blame the victim, train the victim paradigm. It has been said that “no mass disorder afflicting mankind was ever brought under control or eliminated by attempts at treating the individual.”46 Injury is, indeed, a mass disorder requiring urgent preventive action. To control this problem we must move beyond talking to individuals about safety and embrace the wide range of intervention options available to us.

Intervention strategies fall into four main categories—sometimes called the Four E’s:

Each of these approaches is described below.

Education encompasses a wide range of strategies that range from one-on-one education to initiatives that educate society and eventually influence social norms. Health education and health promotion, although criticized by some in the past as ineffective, have much to offer the field if used strategically. We must, however, move beyond a preoccupation with reaching individuals with brochures, fliers, posters, and overcrowded informational displays. Effective prevention frequently requires modification of the nature of the hazard or of the physical or social environment, which is usually the purview of engineering or enforcement. This has led to suggestions that we should focus on engineering solutions rather than educational approaches. In reality, there is no place for either/or; we need both.47 Little is accomplished in our society without the commitment and involvement of groups of people. Mobilization of this valuable resource—be it parents, health care providers, legislators, law enforcement agencies, the media, product manufacturers, or funding agencies—requires the ability to influence knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. The behavioral sciences can also help us identify barriers to change and those factors that predispose, enable, or reinforce change, whether at the individual or national level. Trauma nurses who wish to present educational programs are encouraged to identify, and consider as a resource, professional health educators and behavioral scientists in their organizations and communities. They may also choose to review a recent textbook by Gielen et al. on behavioral approaches to injury and violence prevention.48

Engineering involves engineering out the hazard (such as designing safer products and safer roadways) or using engineering and technology to protect the person in an energy-transfer situation (helmets, restraint systems, crumple zones in cars, automatic sprinkler systems). After injury has occurred, engineering approaches include the development of technology to enhance early warning and emergency response and, of course, the technology associated with management, rehabilitation, and reintegration of the injured person into society. Many of the injury hazards in today’s world are the result of products or environments that we have created with technology. It is not surprising therefore that technology is an important part of the solution. Engineering interventions to prevent injury are so pervasive in our society, however, that we may not notice them, take them for granted, and forget how relatively recent these achievements are. The fact that safety sells, so evident in current motor vehicle advertising campaigns, is a very recent development in our society and the result of years of injury prevention and consumer advocacy. Indeed, each step forward in road design, product modification, product labeling, policy and legislation, and changed social norms about injury has been hard won.

Enforcement is an oversimplified term for a wide-ranging area that involves the development and enforcement of law, regulation, and policy. Federal, state, and local laws and regulation have been used to advance injury prevention in numerous and varied ways.49 For example, laws and regulations have been used to establish and fund federal safety programs; create a mandate for EMS systems development; mandate hospital reporting of external cause of injury codes in 26 states; require the use of seat belts, child safety seats, booster seats, bicycle helmets, and other safety equipment; establish graduated driver’s licensing, speed limits, and traffic control regulations; regulate the manufacture and distribution of consumer products; set safety standards for schools, school buses, child care facilities, health care settings, and the workplace; control high-risk behaviors such as drunk driving; establish building codes; set standards for vehicle design and performance; and create trauma registries and other data systems. Tort law or private litigation has been used successfully to protect the public from unsafe products.49 This has been achieved in several ways, including seeking compensation for victims of negligence and deterring, through liability, negligent practices by companies.50,51

Despite numerous successes, gaps in some existing laws compromise both coverage and effectiveness.49 Additionally, the effect of any law, regulation, or policy is closely linked to its enforcement. Challenges to enforcement are not limited to inadequate law enforcement resources. Those responsible for enforcing a law or policy must believe in the law, their ability to enforce it, and the utility of that enforcement. Building support for enforcement may be as important as creating public support for the law, if it is to be implemented. Many injury prevention laws encounter powerful opponents and are challenged or overturned. Achieving passage of and defending injury prevention legislation usually requires compelling data and extensive and prolonged advocacy efforts. In 1981, Lawrence Berger suggested that six conditions be met when the implementation of injury legislation is contemplated. These are that one “be thoroughly convinced that the bill addresses a strikingly important issue. One should have evidence that the bill’s action can be effective; support from judges and police officers that the law can be enforced expeditiously; economic estimates that excessive costs will not be involved; legal counsel confirming the constitutionality and compatibility of the proposed law with existing legislation and ordinances; and broad-based support from constituents.”52 Clearly, writing, passing, and implementing injury prevention laws is not the sole responsibility of lawyers, legislators, and the law enforcement community.53 Elizabeth McLoughlin, a tireless injury prevention activist, has documented many of the lessons learned in California’s prolonged efforts to achieve legislation requiring the use of helmets by motorcyclists.54 One valuable advocacy lesson, which she continues to develop and apply in other areas of injury prevention, is the power of using “the authentic voice of survivors and family members who have been affected” in support of legislation.54,55 Because of their expertise and personal experience of caring for trauma victims, trauma nurses can make valuable contributions when they join efforts to develop and advocate the passage and implementation of injury prevention laws.

The Haddon Matrix (described previously) can be used in a second way to assist in the identification of possible interventions. This is accomplished by thinking about what interventions might be used to address risk factors present in different cells of the matrix. Pre-event phase interventions attempt to reduce the number of events with the potential to cause injury: prevent car and bike crashes, falls, house fires, ingestion of poisons, assaults, and so on. Examples of such interventions would be graduated licensing programs for teenage drivers, limiting the number of hours driven without rest by truck drivers, enforcing speed limits, legislation that penalizes people caught driving while intoxicated, putting traffic-calming measures in place in areas with many pedestrians, mandating use of safety harnesses for construction workers, enforcing building standards in nursing homes, and closing beaches when there are strong currents. Event phase interventions attempt to reduce the number and severity of injuries that occur in these events. Examples include seat belts and air bags, enhanced vehicle crashworthiness, bicycle helmets and handlebar design, bulletproof vests for police officers, smoke detectors and automatic sprinkler systems, controlling access to lethal weapons, prevention of osteoporosis, and physical conditioning of athletes. Postevent phase interventions attempt to prevent complications and optimize outcome. Those most familiar to the trauma nurse include emergency medical management, medical care, and rehabilitation. Others include improving the integrity of vehicle gas tanks to reduce the chances of postcrash fires, early detection and notification of injury, preventing entrapment, improving health insurance status and social support structures (to optimize rehabilitation), and job retraining.

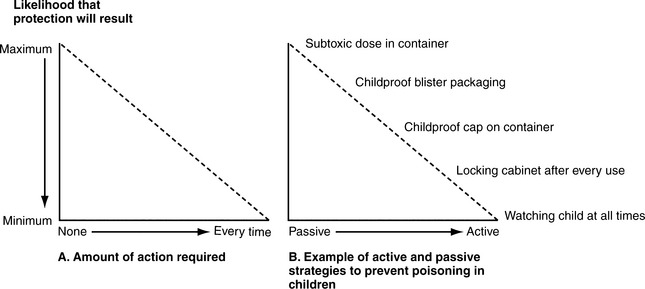

Injury prevention also uses active and passive strategies. An active strategy is one that requires a person to act each time he or she, or the person he or she hopes to protect, is to be protected. A passive strategy will afford protection without action on the part of the person to be protected. All intervention strategies lie on a continuum from entirely active to entirely passive. Seat belts, for example, are not entirely active. They require that a person fasten the seat belt each time he or she gets into the vehicle but, once fastened, the belt will protect the person for the duration of the trip. Figure 6-156 illustrates the relationship between the type of strategy and the likelihood of prevention effectiveness.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree